Joseph Stiglitz (the public figure) has had a bad case of punditry for the past 25 years. Joseph Stiglitz (the academic) is godly. I discuss a few of his papers below.

Markets are perfectly competitive, and indeed welfare maximizing, when markets are complete, there are no externalities, and there is perfect information. Stiglitz is concerned in all three of these papers with what happens to markets when information is imperfect.

i. Share-cropping

Share-cropping is really a strange arrangement if you think about it. Imagine the crops are split 50-50 between the landlord and tenant. The tenant then faces a 50% marginal tax rate on any additional effort they put in, which leads to them putting in a level of work which no one would prefer. If the landlord had charged a fixed rent, the marginal tax rate on additional effort is 0. He could get a higher rate, on average, and the tenant could also get a higher rate than before.

There must exist some advantage of sharecropping, which is that the landlord is offering insurance. If the harvest goes poorly, then the renter is in less danger of starvation, as the landlord bears some of the cost. People in agriculture really, really want insurance — they need a minimum level of income at all times, or they die. They cannot maximize expected value over time! The landlord is larger, and is thus able to bear more of the risk. Obviously it is not so good when the reason the crop failed is correlated with nearby places – a drought, or a big storm, for example – but the landlord can offset idiosyncratic shocks. Keep in mind the strangeness of sharecropping for later.

Braverman and Stiglitz deal with a secondary mystery of sharecropping — why does the landlord involve themselves in selling everything to the tenant? Landlords will lend, sell fertilizer, tools, and seed, and even sell regular commercial products to their tenants. If they are a monopolist, this is entirely unnecessary — they can extract as much as they can without needing to involve themselves in sidelines they might be inefficient in providing. If they are not a monopolist, (and we presume no persistent cognitive biases), doing this doesn’t allow you to get any more revenue. So why, then, do they do it?

By changing the terms and conditions at which they sell various services, the landlord is able to elicit more effort, and shift the production-possibilities frontier (a graph representing the greatest combinations of goods which are able to be produced) outwards. This can benefit both parties, although it does not necessarily need to – the gains to the landlord will, however, exceed any losses to the tenant. For example, suppose it would increase production if the tenant undertook a more risky mixture of crops. The landlord could sell the seed for a below market price, in order to induce changing to those crops.

ii. Efficiency wages

Suppose we are in a world which is perfectly competitive, but for one thing — employees have private information about how hard they are actually working. This is an extremely plausible assumption, as there is a lot of room to take it easier on the job. In a state of perfect competition, any person could leave a company and get another at the same price without any friction. How, then, could a company induce greater effort from the employee?

Shapiro and Stiglitz argue that companies raise wages above what is market clearing. They forgo hiring out to where marginal cost equals marginal revenue, and on the whole under hire. The point is to make it more costly to change jobs — if you left, you could not effortlessly get the same job at a different firm. You must work harder, but are compensated for it, thus making it raise total utility. At the same time, it explains why unemployment will be inevitable, even if workers have perfect information about all job opportunities and prices.

This has been empirically tested; an overview can be found at the end of these slides from Acemoglu. I want to focus on a particularly elegant test of it, Capelli and Chauvin 1991. Many companies have plants which are spread out geographically, but whose wages rates are uniform, and generally decided by union negotiation. Since different places have different prevailing wage rates, the premium of the company’s rate differs. The efficiency wage hypothesis implies that places with a higher relative wage premium will have fewer dismissals for shirking – and indeed, that is what they find.

iii. Credit-rationing

Why do companies ration credit? It is a basic tenet of markets that, left to their own devices, prices will rise until the market clears. Why does this not occur, especially in the developing world, even when there are no apparent restrictions on the rate of interest?

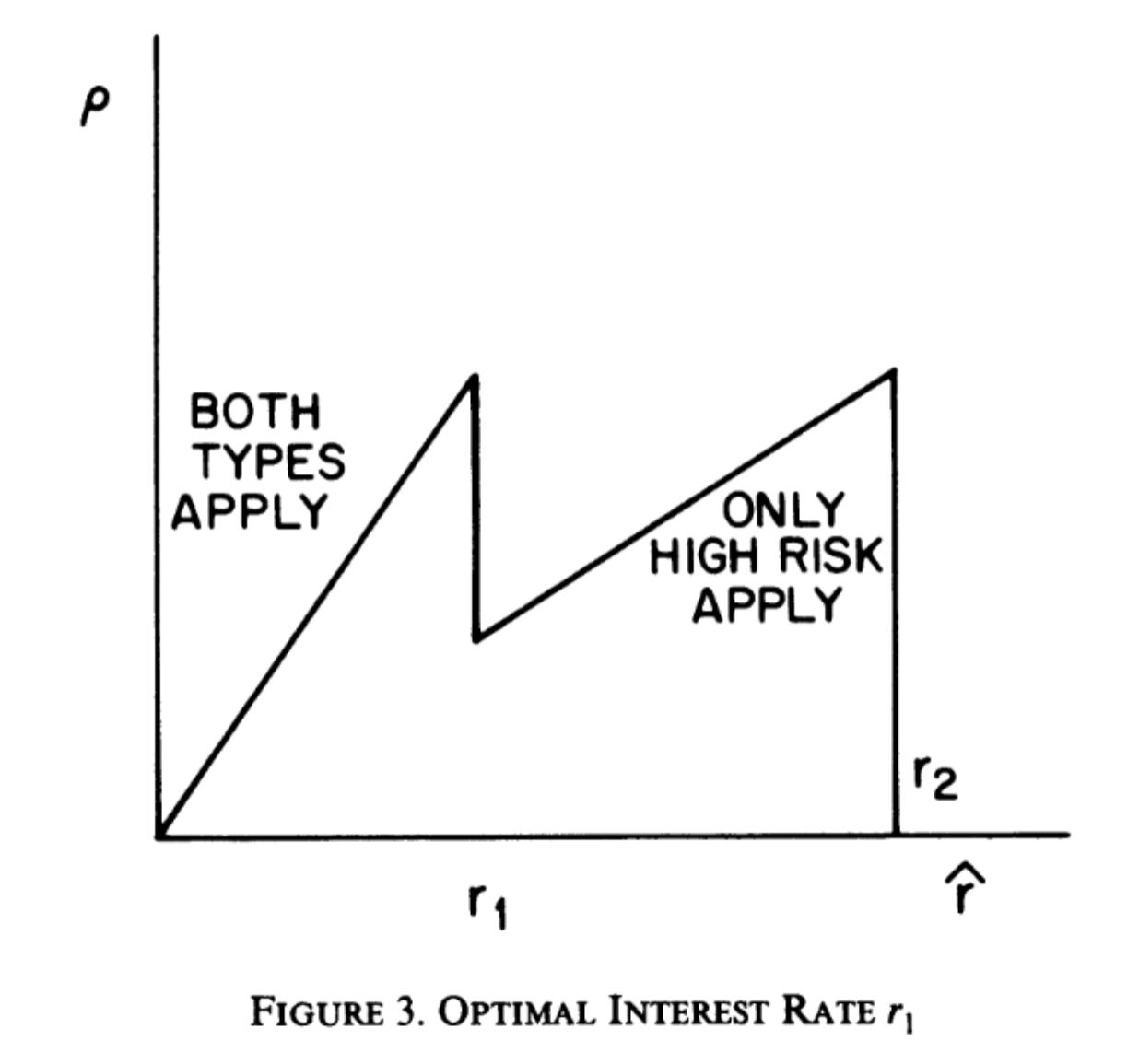

Stiglitz and Weiss offer up a clean model explaining things. As the lender raises interest rates, the nature of the borrowers do not stay the same. The borrowers have private information about the characteristics of their projects. The lender cannot compel the precise behavior they want either. People could borrow for a risky project, and declare bankruptcy if it doesn’t work out — or they might skip town entirely. If raising interest rates pushes away enough lower yield, but more consistent, projects, the lender might find themselves lowering their expected profit, not raising it. Thus, credit rationing.

Figure 3 here illustrates what is going on. Profit is on the vertical axis, and interest rate on the horizontal. At some point, low risk applicants are driven out of the market. From how things are configured, it is implied that there are two equilibriums, but there could very easily be one, low interest rate equilibrium, where loans are randomly allocated among identical (from the bank’s perspective) applicants.

An immediately striking application is explaining why shares exist. The Modigliani-Miller theorem states that, under some strong assumptions, including perfect information, the value of a firm is totally unconnected to how it is financed. Let’s think back to why sharecropping is weird. We would prefer that the marginal “tax” on additional work is 0, and this makes debt financing seem much more attractive than equity financing. However, the return to debt financing is bounded, and the return to equity financing is unbounded. Equity is better able to capture the riskiness of projects when it is difficult to tell how uncertain the project is.

iv. Why Stiglitz

I find Stiglitz’s best papers beautiful. I hope to write papers like his – taking an interesting but strange fact about the world, and finding precisely what needs to be changed for it to become stable or even optimal. I must caution, however, against falling into the same errors that Stiglitz has, in public life. Markets fail. Markets fail a lot, in fact. A great deal of government intervention is justified and needed. One must not mistake the ideal government for what will actually happen, however. Governments fail too – and often far worse than markets ever would. Be not naive in either direction – government is not perfect, but neither are markets without faults.

What about his famous optimal tax paper?