Why do people behave so oddly around risk? A common thread of laboratory research is that people exhibit a fourfold pattern of risk attitudes. Specifically, they take big risks when faced with low-probability gains, are risk-averse over high-probability gains, are risk-averse over low-probability losses, and are risk-seeking over high-probability losses. People consistently overweight low-probability events, and underweight high-probability ones. The implied levels of risk-aversion are inconsistent, and people behave differently when a choice is framed as gaining something, versus avoiding a loss.

One possibility is that people aren’t actually behaving this way because there is risk – rather, they are behaving this way because the decisions are complex. Ryan Oprea has a recent article in the American Economic Review arguing that “Decisions under Risk are Decisions under Complexity”. In it, participants are asked how much they are willing to pay for a set of 100 “boxes” which each have some dollar amount. Sometimes, this is a lottery – one of the boxes is opened, and you are paid the dollar value inside. Other times, however, you are simply paid the average value of the boxes, no matter what, in what they call a “mirror. So, you might have a 90% chance of $25, or 90% of $25, the latter of which is totally riskless. If people’s odd behavior is driven by fear of risk, then it should only happen in the actual lotteries – but Oprea shows that it occurs even when there is nothing at risk whatsoever.

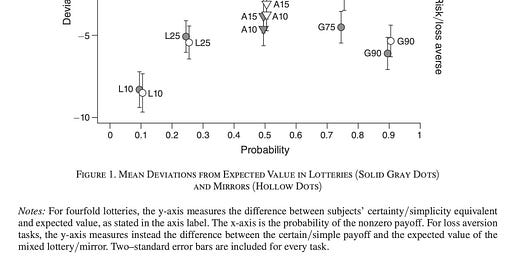

We can see the effect in the graph here – people behave in different ways for losses and gains, and they behave the same whether there is anything actually at risk.

It’s not clear that what they’re testing is all that meaningful, though. I was discussing this with some psych professors at Berkeley, who asked cuttingly what it would mean if the entire study were conducted in Russian. Would people not pick at random? Would they not replicate the same pattern? Are you actually finding any sort of meaningful complexity, or just showing that people make bad decisions if they don’t understand what you’re doing?

And so the results are crucially dependent upon participants not understanding what is going on, and picking things in a suboptimal manner. A comment by Banki, Simonsohn, Walatka, and Wu reanalyzed the original dataset, and showed that the fourfold pattern and loss aversion appear only in the 75% of people who failed comprehension checks. Removing those people, the usual pattern returns.

The original study had an online sample, so people have replicated it under lab conditions. A direct replication showed it did not hold up. Simply reading the instructions aloud cut comprehension errors from 49 to 7 percent. George Wu, one of the authors in the first comment, has a separate replication, again showing that with clear instructions, the effect disappears

You might say that the complexity is the point, but this would hardly be an interesting finding. What if you lied to the participants about whether there are lotteries or not. The participants would be in no different a state than if you worded it confusingly – they would act as though there were lotteries, because they believed that there were lotteries. The stimulus Oprea chose can’t get at anything deeper than that.

I will shamelessly tie this back to some earlier writing of mine on the value of life. The standard method of evaluation is to take what people are willing to pay for small changes in mortality risk. Everyone agrees, though, that for whatever reason, this is afflicted by irrational behavior. It is not that we should die more – it is that we cannot be said to have any particular price which we put on our lives!

The relevance of Oprea’s paper ultimately comes down to how much attention you think people are paying to the world. It is absolutely plausible, to me, that people shut down when facing complex choices. It is not knowable how much the conditions of Oprea’s study map onto the real world. Since being in person and having the instructions read aloud was sufficient to annihilate the claim, I would imagine an analogue to this with reasonable stakes would also not have these same patterns. On the other hand, the world is much more complicated than their setup.

In short, we just don’t know.

I would like to acknowledge my debt to Shengwu Li, whose thread pointed me to the direct replications, and who screenshotted the images first.