There are many questions we would like answered which do not have associated markets. For example, we would like to know how much we should spend on mitigating an externality, or what people believe their rate of inflation will be in the next year. Can we get any meaningful information about people’s preferences in the absence of prices?

Let’s take a specific case. Let’s say we want to know how much people will pay to clean up a public lake. We ask them, and get a value – say, half a million dollars. We could also ask them how much more they would, personally, value the lake being clean, and multiply this by the estimated number of people who would come to the lake. We might also ask how much they would be willing to pay to clean up five lakes, inclusive of the one asked about previously. This is called a contingent valuation survey.

The trouble with these contingent valuation surveys is that the numbers people give do not add up in a coherent way. Hausman (2014) and Diamond and Hausman (1994) offer excellent surveys of the problems. People give values that contradict their other responses. They might, for instance, value cleaning up five different lakes at the same value which they give for each of the lakes individually. They don’t know much about the topic – nor will they ever – so it can hardly be said to be a considered opinion. It is well-known as well that hypotheticals are persistently biased upward. If you ask people whether or not they would buy a good at a given price, they will give values far in excess of what they would actually agree to. Making these values meaningful requires an ad hoc adjustment by some factor. Finally, the valuations given are acutely sensitive to the way in which they are phrased. Changing the question from “how much are you willing to pay” to “will you accept” should not affect the average value, yet it does.

Similar problems occur when respondents are asked to give their beliefs about the future. There can be a wide gap between what people say, and what they actually do. People might indulge in emotional statements about what they believe, and then actually act in a way completely at odds with what they say they believe.

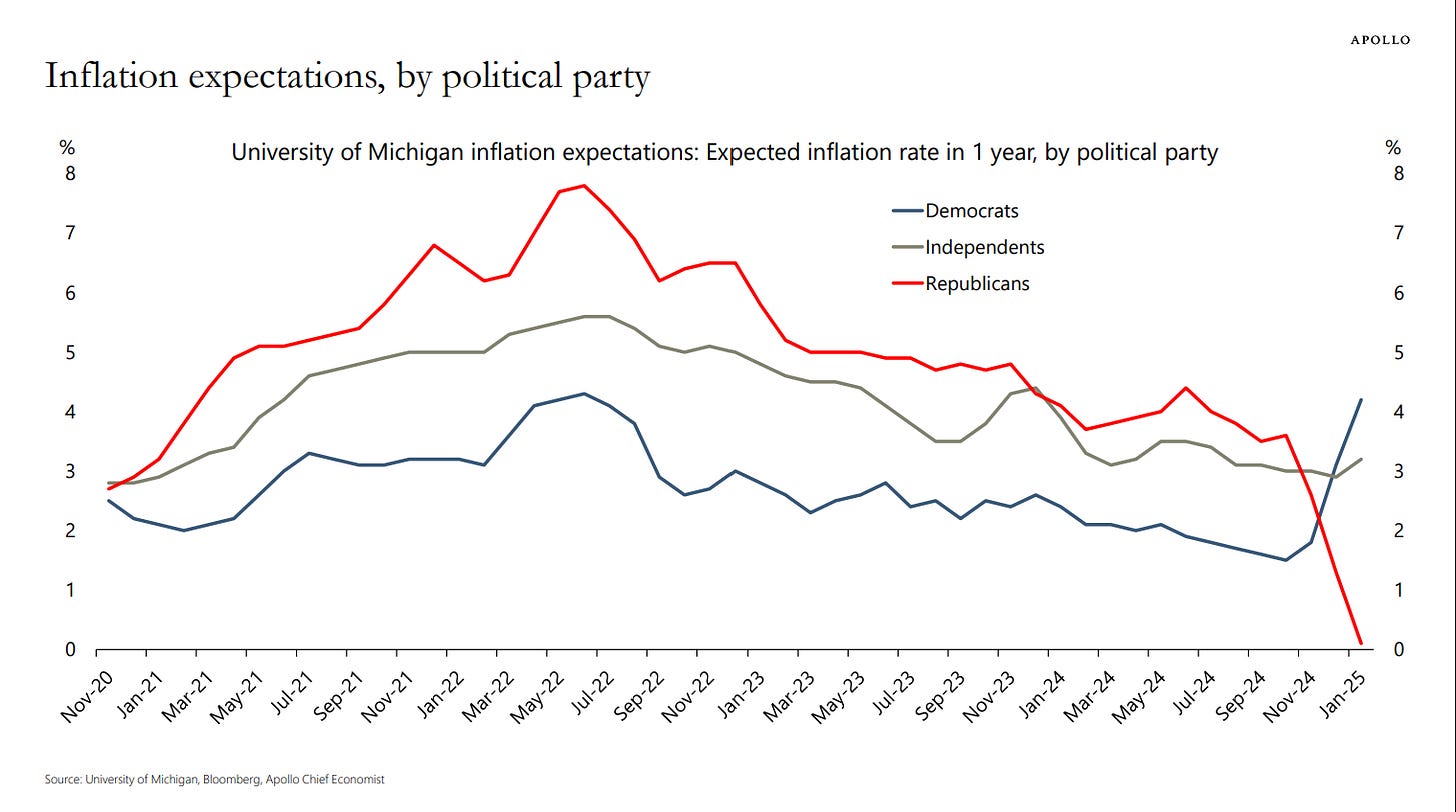

The cleanest example of this is in the University of Michigan inflation expectations survey. They handily break down the expected inflation rate by the political party of the respondent – now what might have happened in November 2024 that caused such a sudden change in beliefs about inflation a year from now? It is implausible that this is due to a “real” change in beliefs. I don’t see Republicans rushing out and buying all the bonds they can, and I don’t see Democrats pulling their money out for consumption now. People are just expressing what they wish to be true.

The inflation survey suffers from similar problems as contingent valuations, and adds another – stated opinions being influenced by the news. If you ask people what they think inflation will be, their answers actually track (with reasonable precision) what inflation actually ends up being. If you ask people how much they expect the prices they personally pay will change, they arrive at considerably higher and more dispersed answers, which are more affected by price swings in salient goods like gasoline. (van der Klaauw, Bruine de Bruin, Topa, Potter, and Bryan, 2008) (It is possible that this difference is due to quality improvements, which could result both in higher quality goods being sold, and higher prices observed. I have not come across any paper considering this).

The obvious explanation is that people are somehow catching wind of what we think inflation expectations “should” be. Meanwhile, their stated beliefs about what they actually expect to pay stay the same. We can’t even be sure that people aren’t just engaging in aimless grousing about prices increasing everywhere, and whether or not they actually expect the prices they personally pay to go up. Additional evidence for this is that participating in surveys about inflation directly changes people’s expectations in the future, as shown by Kim and Binder (2023).

The reason behind this is that people seem to pay a cost to think about this. People have their gut feeling response, and then have their actual response that they would arrive at if they thought about it more. With no consequences, people don’t have any reason to think deeply about what they actually want. Treat the cost of making a decision as fixed. People will think more about what they actually want when the effect of their decision, weighted by their ability to influence the outcome.

All of this is quite simple, but it should suggest that the policies which we vote for have very little relationship to what we would want if we contemplated it perfectly. The possibility of us swaying a decision is tiny. The benefits to making the correct policy decision, while large, must be weighted against this. Why would anyone invest in finding out information about the world, at considerable cost to themselves?

This would be only a small problem if people’s beliefs are unbiased. If voters are choosing between two candidates or possible issues, then it doesn’t matter if some of them vote at random. More people voting at random raises the probability of being the deciding vote and thus the returns to discovering information about the world.

The trouble is that voter beliefs aren’t random. Instead, they’re biased. They favor things which sound nice, but aren’t so. We favor tariffs because it sounds like strong, muscular action – never mind that it should make America weaker! We are inclined to dislike foreigners, so we blame our problems on them. We distrust outcomes we can’t control, so we try and regulate more. Forgive me for dispensing with subjectivism when it comes to what policies we should have – some of them are better, and we are systematically biased away from them.

To get what we actually want, we need prices. I discussed why I support capitalism earlier – you can consider this part two. I think we should move as much as we can out of the sphere of government decision making, and into the hands of people. If they lack prices – that is to say, real world consequences – people’s preferences are meaningless. I would not go so far as to say that they do not exist, of course. People do indeed have hypothetical preferences, and you can, to some degree, elicit them. It’s just that you cannot accurately elicit them.

Hard disagree on this one. It is precisely because voting aggregates preferences in a different way than markets that we should keep voting. Markets weigh people’s preferences on how much they are willing and able to spend. There are several contexts where people unable or unwilling to spend should still have their preferences kept into account. Markets satisfy the wants of people (as long as they can pay) and disregard their needs. Voicing needs through politics (not necessarily confined to voting) is complementary to markets. People can understand that their neighborhood needs a public library even if they are, individually, unable or unwilling to pay directly for one. Hence taxation takes money from people who can pay but may not want to, bypassing the relevant coordination problems, and delivers the needed public good.

Of course some externalities are easer to estimate than others such a economic and public health harm of CO2 emissions and other form of air and water position.