Auctions on the Internet

The magic of Google

Every time you type something into Google, an auction is run. In milliseconds, the system takes the bids entered by potential advertisers, weights it by quality, and serves you the relevant results. It is an incredible feat of engineering, and incredibly profitable too. Let’s learn about it.

The system does not require any sophistication from bidders – they do not have to have a bot punch the button each time. Rather, people have the ability to submit bids on keywords, and the highest N bids out of K bidders win a slot, ordered by their bid. Like a second price auction, the highest bidder pays the second highest price. This mechanism is generalized to all m slots, so that everyone pays the valuation of the bidder one slot below them. This is called the generalized second-price mechanism.

This is similar to the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves (VCG) mechanism, which is the mechanism by which we can allocate any number of goods among any number of buyers. To put the mechanism extremely simply, we state our values, calculate how to allocate the goods, and then pay a fee equivalent to the value we are depriving others of having. With one good, this is the second price auction – we are paying the amount which the second highest bidder would have valued it at. With multiple slots, it is no longer the VCG mechanism, because the value we are depriving others is not just the one right below, but also other advertisers who would have gotten a higher slot, but we can show that the revenue to the seller is the same. We don’t implement the actual VCG mechanism because it is computationally infeasible. The way in which you are incentivized not to tell the truth is that you will shade your bid down if all the slots are filled. However, the total revenue will be the same.

Why not have first price auctions? We want humans to be able to interact with the advertising system. The generalized second price mechanism makes it so that you can place your bid and be done with it – you don’t benefit at all by having a robot automatically outbid your opponent. Needing some sophistication to bid is a not inconsiderable obstacle for many of the bidders on keywords, who are often local businesses, lawyers, and contractors. The investments into gaming the system get passed onto the seller either way.

Advertisers pay per click, rather than per view. They pretty strongly prefer this, for a few reasons. It’s more credible. Nobody would want to pay for low-quality, automated impressions, much less impressions that are the result of a competitor. Companies may not trust Google to credibly report how many people viewed their ad.

With pay by click, though, we have to be very careful about what sort of advertising gets shown. Companies which offer products which are extremely lucrative conditional upon being clicked, but won’t be clicked by anyone at all who isn’t going to buy, are going to be extremely advantaged. In other words, the ad space is going to be full of pornography. We saw something similar to this in action when the European Union required giving users the option to choose their browser, and the ones which actually bought space were the much less popular search engines who were also more invasive. (Ostrovsky, 2023)

Therefore, Google weights each bid by a quality score. How this quality score is calculated is a closely guarded, and constantly changing, trade secret. Prof. Ellison estimated (in class) that Google spends about a billion dollars a year just on the weighting team. What we think it to be based on is the click-through rate. This conveniently solves a possible problem, where competitors might pay people to click on ads and not make purchases in order to hurt their rivals. Clicking a ton on the ad indicates that it is relevant and improves their quality score, reducing the price which they have to pay for future advertising. (I just found it elegant). Yahoo did not do this, so Yahoo fell behind.

Google also cleans up the webpages by having a reserve price which is clearly above the short-run profit maximizing price. If they wanted to, they could always accept more advertisements. Remember that, since a reserve price can be set for every keyword, it can never be profitable to set a reserve price such that there are never auctions on that keyword – yet, Google does this.

This can be rationalized by considering consumer search. The exposition of the generalized second price mechanism I have given so far has followed along with Edelman, Ostrovsky, and Schwarz (2007), who consider a simple case in which bidders have independent and private values for the slots. Athey and Ellison (2011) consider an alternative model where consumers are engaged in costly search for an object which meets their needs. Here, reserve prices, rather than increase profit at the expense of consumer surplus, can increase consumer surplus by simplifying the process of looking for relevant things to buy.

What makes the generalized second price mechanism so good is that the transfers are part of the ad targeting. It is not possible for a competitor to offer a discount on the price of advertising, and still have the same quality of advertisements. If a competitor to Google gave a percentage discount to advertisers, while offering the same quality, then people would bid such that their payments are the exact same. (If the quality were lower, then advertisers would bid less.) To actually give advertisers a discount would require picking and choosing them, leaving us unable to tell what the actually relevant ads are, as the auction mechanism tells us.

It’s not at all settled what the correct level of advertising is optimal for firms. The literature is divided on whether it is even with good, with some papers, like Shapiro, Hitsch and Tuchman (2021), claim that the marginal value of advertising firms is negative.

Measuring the effect is extremely hard for several reasons. It is difficult to tie the person who viewed the ad to the person who eventually makes the purchase – for instance, someone might view an ad, not click at the time, but later be inclined to purchase on account of that ad. Relatedly, people will interact with each other people who did not view the ad, which violates the stable unit treatment value assumption and biases your estimates down. Perhaps a kid sees an ad, and then asks their parents to buy it for them. In the online context, you will probably not be able to see this, same when someone views an ad and then chooses to make an offline purchase. People might also change the advertising which they view when they are looking for an item already – an assumption that people don’t do this might be believable in the context of television viewing, but it is a totally implausible assumption when people choose what they search! And of course, ads will influence purchasing behavior for years to come, far beyond any study’s power to detect.

We can, nevertheless, say some things about the effects over the internet, and we can even make better estimates than offline advertisement can. However, our task is hard, probably too hard. People rarely buy when they see an ad, but when they do, they spend a lot of money. This gives us a standard deviation which is way larger than our mean, so a relatively successful campaign with a high return on investment will be essentially undetectable. Lewis, Rao, and Reiley (2013) run through the numbers with typical values from the experiments they ran while at Yahoo. The consumers spend an average of $7 per person, but with a standard deviation of $75. The ad campaign costs 14 cents per customer, and hopes to increases sales by 5%, or 35 cents per person. If we assume a markup of .5, then that’s 17.5 cents in profit, or a 25% return on the investment. So, can we detect this? The R-squared, which is the percentage of the variation explained by the study, will be .0000054. Yes, five zeros. That means that the variation caused by the study is absolutely swamped the idiosyncratic characteristics of the consumers, and also that if your assumptions are even slightly wrong the effect will be swamped. You would be underpowered even with hundreds of thousands of consumers.

One really impressive study of the effect of advertising is Lewis and Reiley (2016). What makes their study special is that they can track the effects of online advertising on offline purchasing, with data both on people who clicked and didn’t click the ads. This is because they’re only looking at the effect on the population who were already in the retailer’s database, who are then matched against Yahoo’s database. With a sample of 1.3 million, we can then show people ads at random. (Yahoo used to have banner ads on the home screen). The campaign was effective in increasing purchases by five percent, although we know nothing about the effects on profits. (The anonymity agreement they signed was quite harsh).

The study does go to show that, for things which are not exclusively online retailing, measuring the effect of advertising without exceptional data is essentially impossible. 93% of the increase in purchases came in store, with 78% by customers who had never clicked on it. If you’re just advertising on searches, it’s over. It’s hopeless. All you have is time-series, and that sucks.

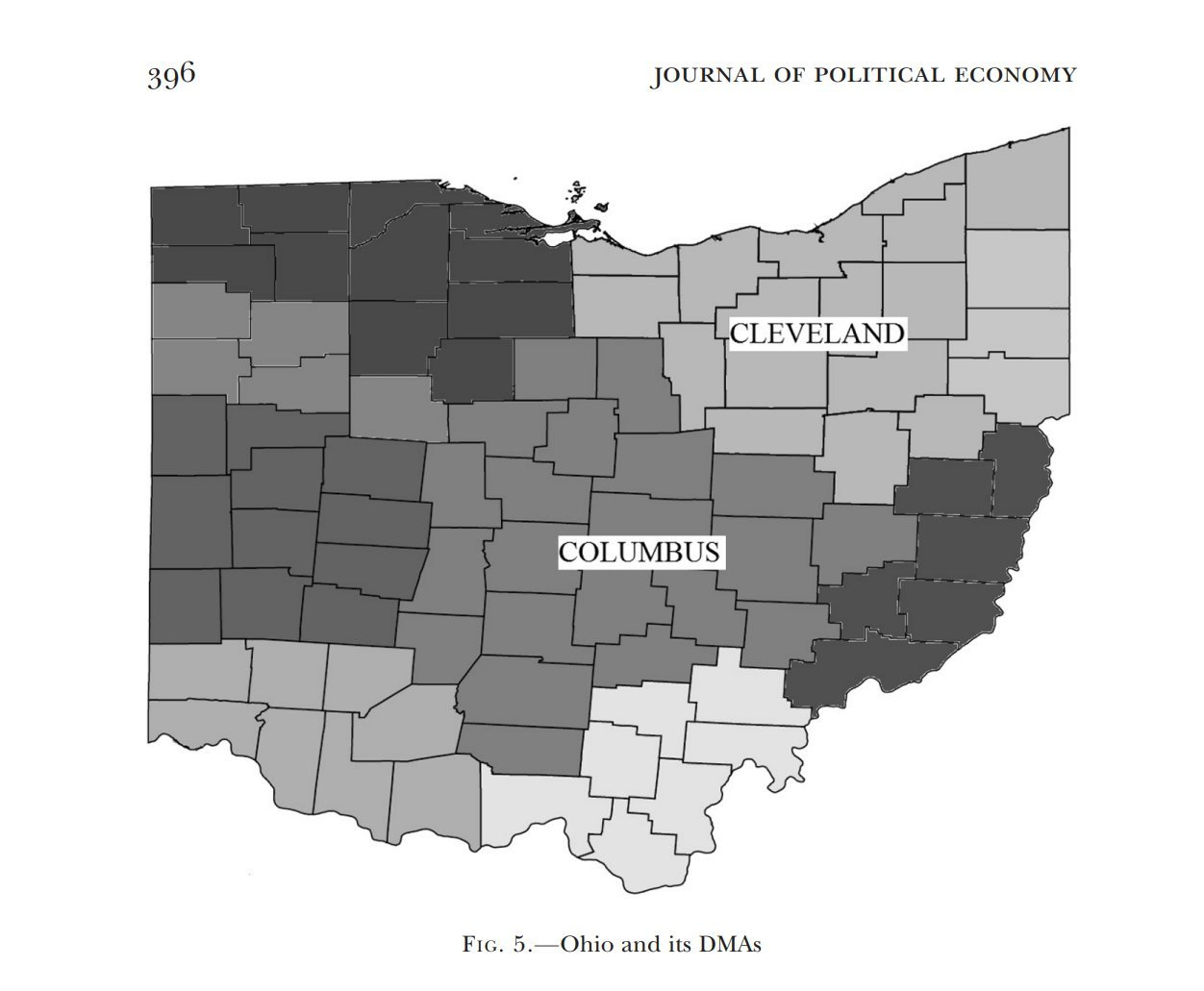

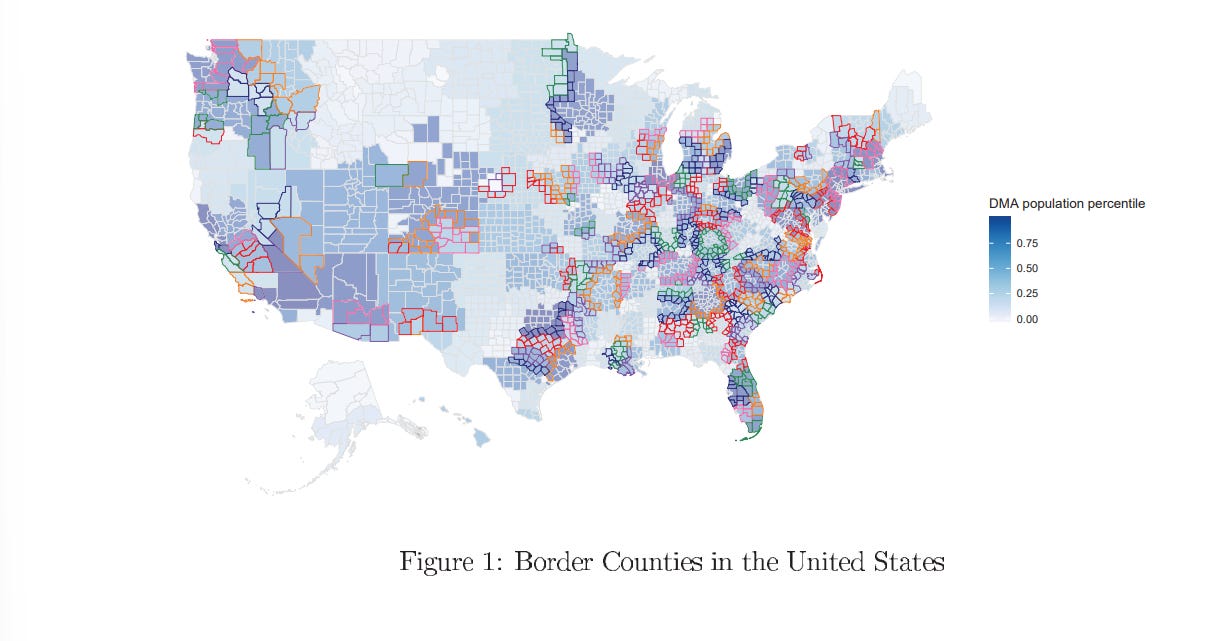

We can compare and contrast these to estimates of advertising in the field, which tends to find that the return on investment is actually negative. Shapiro, Hitsch, and Tuchman (2021) really is the best paper on this for sheer range. As mentioned, advertising is endogenous , so they get exogenous variation from media markets in America. These are centered around major cities, and extend outward into the countryside.

Where one market leaves off and another begins is somewhat arbitrary, and so you can compare the counties at the border. The argument is that, after controlling for the average tendencies of the area and for the average tendencies of that time period, changes in ad buys can give us the true effect. This leaves us with lots and lots of counties which can support the effect.

Supporting this are the institutional details. Ads tend to be purchased well in advance of when they will actually be aired, and so ad-buyers find it difficult to respond to predicted local and idiosyncratic demand shocks.

With variation in hand, we can see how purchases vary for the 288 brands in Nielsen Homescan which they can link to advertising. The results are not good. For basically all of them, we can reject significance. For much of them, we can reject a positive return on investment.

Part two of this blog post will deal with eBay. In particular – what happened? Where did all the auctions go? And why?

Brilliant breakdown of how Google turned auction theory into infrastructure. The quality weighting bit is really underappreciated tho since it solves the adverse selection problem (low-quality ads just spam clicks) and the strategic gaming issue at once. What's less obvious is how this creates a moat nobody can replicate becase the transfer mechanism is the targeting itself, so any competitor discounting just shifts bidder behavior to equilbrium prices anyway.

I think there’s some educated guess that can be made about roughly how this algorithm works, thinking about how one would naively combine PageRank with an ad system.