Do Morons Make Prediction Markets More Accurate?

In the past few years, we have seen the widespread popularity of prediction markets, like Kalshi or Polymarket. As a fan of prediction markets, I find this extremely exciting. Prediction markets are an incredible way to aggregate information, and get accurate predictions on the likelihood of an event happening.

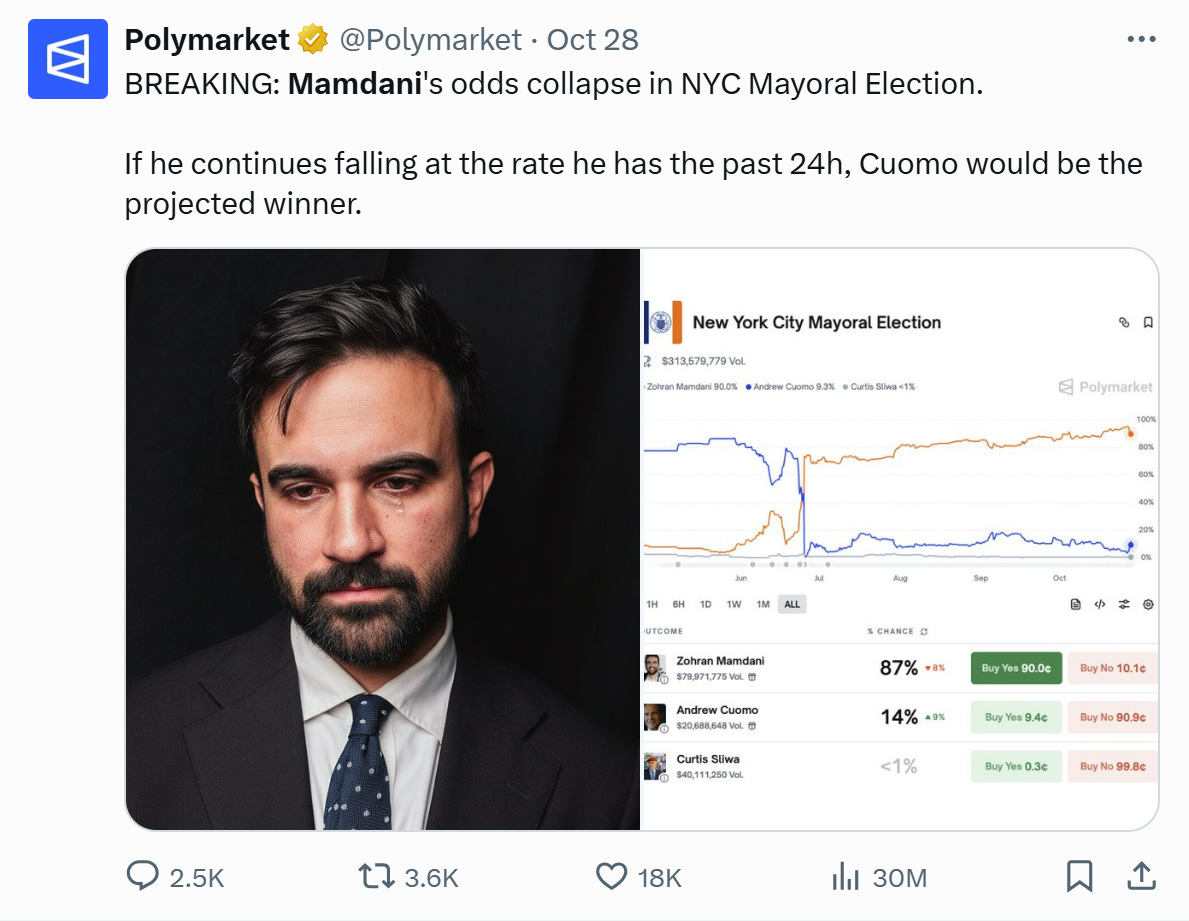

I am instinctively displeased, however, to see how Kalshi and Polymarket promote themselves, especially on Twitter. Whoever they have running the account seems to have no idea how their product works in even the most trivial respects. Take, for instance, this tweet, which seems unaware of how odds should be a first order Markov variable.

There are lots of tweets like this, which I will not provide. (I do not like crawling through advertisements). Their goal is, of course, to get the attention of morons, who will then bet on it. They are gambling markets, and thus profit when people make trades, whether or not those trades are accurate. However, we might reasonably be concerned that a deluge of uninformed rubes will make the odds less accurate.

We should quickly review how prediction markets work. There is some event we are interested in, which can be resolved as some set of yes’s and no’s. For instance, we might want to know who the next Mayor of New York City will be. Suppose the current odds were 50-50 between Candidate A and Z. This would mean you could buy a token which will be worth $1.00 if Candidate A wins, and $0.00 if they lose, at a price of $0.50. Bettors are not buying it from other traders at a mutually agreeable price – that would be too complicated to make work – but are instead buying it from a liquidity provider, who puts money into the market by buying a balanced share of both yes and no. The liquidity providers are compensated by a fee for making the trade. The price changes automatically as someone buys more of yes or no, and follows a logarithm. The more liquidity there is, the less a single trade affects the price of the market. Liquidity providers profit when there are small changes in price, and lose money when there are large changes in price. Polymarket does this automatically, while Kalshi uses Susquehanna River Trading to provide liquidity. They also have an order book, where people list their own willingness to buy and sell, and place limits on how much they can lose from adverse selection.

Imagine there are two types of traders, informed and uninformed. Alternatively we could say that there is a continuum of traders by the accuracy of their predictions, but that seems needlessly complicated. Both types of traders pay a fixed cost to enter the market, and face some cost of acquiring capital. I conceptualize the fixed cost as spending a binary amount of time to receive a signal, and not allow for someone spending more time to acquire more of a signal.

First things first, more uninformed traders allows the trading fee to be smaller, and are necessary for the market to exist at all. We need people to enter with no information in order to make providing liquidity worthwhile. Otherwise, liquidity providers would lose money on every trade, as they get picked off by people who know better.

Beyond this, though, we might be concerned that if uninformed traders are biased they could shift the odds one way or another, and this brings us to the central argument of this article.

If the only cost that informed traders face is a fixed cost to spend their time on prediction markets, then morons, even biased ones, will improve the accuracy of the prediction market. By increasing the stakes, it allows more people to pay the fixed costs of acquiring a better signal. If, however, traders face no fixed costs, but do face increasing costs as they seek more and more capital, then attracting more morons would lower the accuracy of a prediction market. If traders face both, then attracting morons will first raise the accuracy of the prediction market, then lower it.

Which prevails? I do not know. However, we should not be cavalier about advertising prediction markets. It is possible that what is privately optimal, and socially optimal, are not aligned.

A possible way to tackle this is to regress trading volume on Brier score, which is a measure of how accurate the prediction markets were. Alternatively, I think we could pull out a cost of capital from the percentages that nonsense markets trade at. There are people who have positive amounts on Jesus returning this year, because they expect the people betting no will have to pull their money out before they do. I think it should be possible to infer the cost of capital from this, although how is not obvious.

It seems like you could plausibly use sports betting as a proxy for measuring/estimating the marginal effect of dumb money. It also seems plausible that you could have some exogenous shocks to the interest of ‘dumb money’ in particular outcomes (e.g. random rescheduling pushes a match to a more or less desirable timeslot) that would let you measure their effect on accuracy

Isn't the market for Jesus Returning just a bet on interest rates? If you are certain the answer is No, but paid a year later, you should only be happy buying with a No price of 1 minus the interest rate. Buying Yes is equivalent to Selling No, so if you think that No is over-valued, ie that interest rates will rise soon, then you can profit by buying Yes today (and selling it when they do rise).