Either Dishonest, Incompetent, Or Both

The state of the evidence on sex trafficking

Yesterday, Nathan Witkin published “Meta’s Child Sex-Trafficking Problem” on Jonathan Haidt’s blog. He was covering recent accusations against Meta of them tolerating sexual trafficking, in particular of children, which I will decline to cover at length. That’s not what I’m interested in. Instead, I am concerned with gross research misconduct by the study on which he relies to estimate the number of people who are sexually trafficked in America. The piece by Mr. Witkin should be pulled from circulation, and an apology issued.

In it, he wants to give some sense of how important Meta’s role, through Facebook and Instagram, is in child sex trafficking. He claims that 1.7 million people are sexually trafficked every single year, and then discusses what share Meta was responsible for. If the figure is true, and with an ad hoc rounding down to a million, it would imply that 100,000 minors are trafficked off of Meta platforms every single year.

This leapt off the page as totally unbelievable. Lest it not be clear, 1.7 million is a lot of people. If you had a high school of 2,000 individuals, that would imply that 10 people are trafficked every year. One would think that they might have heard about it – that every family would have someone who was trafficked. And yet, we don’t. What’s going on? How can we have a number that stupefyingly large? In short, no, it is not real, and to get it the researchers had to misrepresent what they were doing, while making laughable methodological decisions.

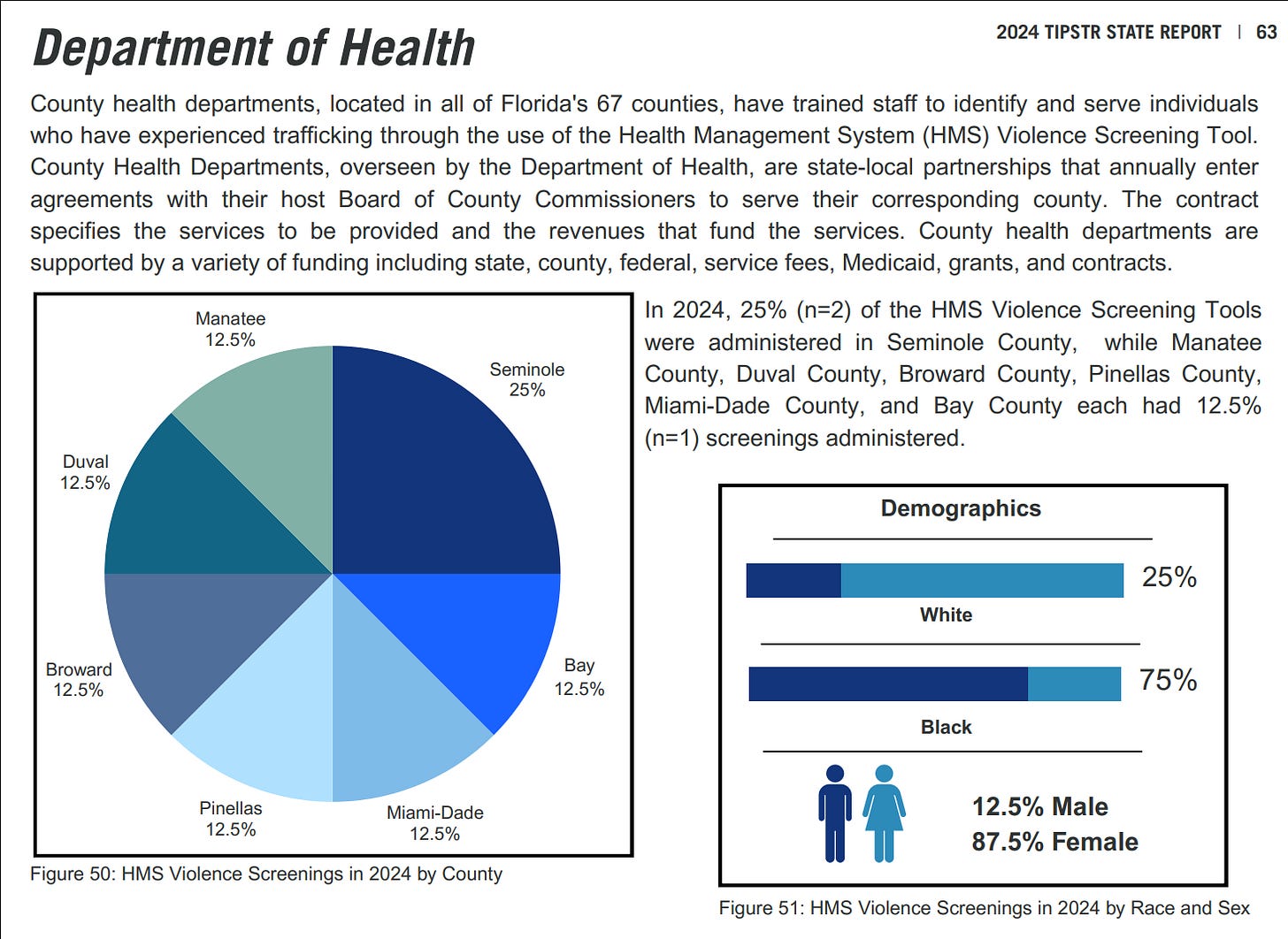

The claim is based around several “studies” purporting to measure the rate of sexual exploitation and human trafficking in Florida and Sacramento County. I hesitate to describe these as studies – that might imply that something can be learned from them. They are the accretion of people with more Excel graphs than good sense. Take this howler, where for some reason they decided to graph out a questionnaire which was used on … 8 people.

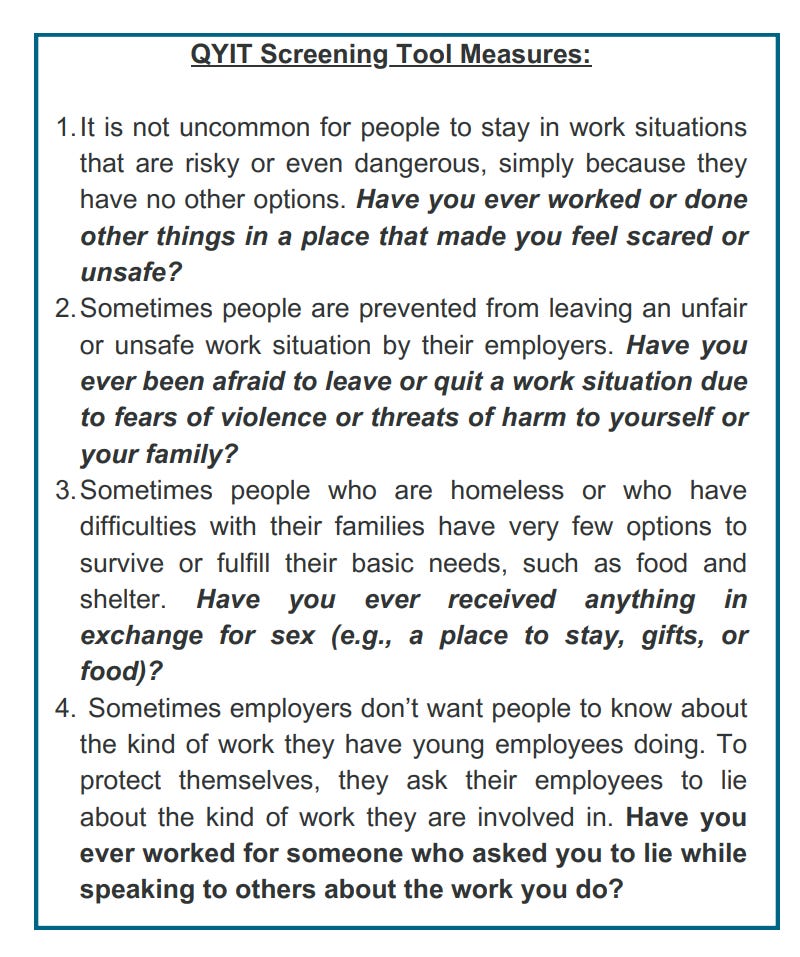

But enough of the insults. The high end study, and the largest, is on Florida, by a large team of authors led by Prof. Joan Reid of USF. The central piece of evidence behind the claim is a survey which they administered to 2,500 Floridians. It consisted of four questions, only one of which, question three, allows us to say anything about sex trafficking.

Something well-known about surveys is that sometimes people will not tell the truth. It’s the so-called “Lizardman Constant” – for whatever reason, some portion of people will either not cooperate with you, or will misunderstand the question, or will give the wrong answer. Scott Alexander argues that even the most obviously nonsensical questions will get a small fraction – say, 4 percent – to answer yes. Perhaps there were some people who interpreted “well, my husband got me a present on my anniversary, so I did receive something in exchange for sex”. Or perhaps there were some people who just said yes for the hell of it. It’s naturally concerning that 4% of people answer yes on question 3.

They need to validate it by comparing the fraction of people who answer yes to the fraction who were actually trafficked in a sample where you can ask followup questions. Well, that’s what they claim they do. The only trouble is, they don’t. What’s more, they hide this, and make it appear as though they did something which they did not.

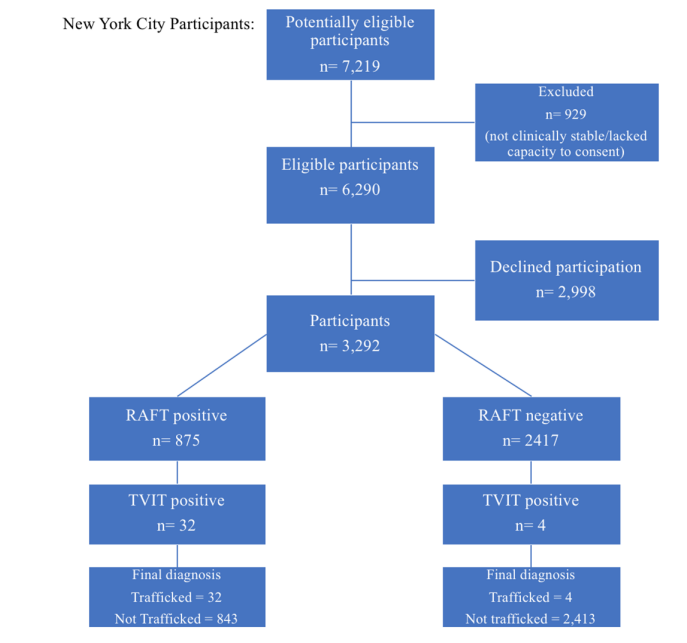

They prominently cite a study, Chisholm-Straker et al (2021), which used a sample of people asked at entry into an emergency room. For simplicity, we’ll use their NYC sample. 3,292 people entered the questionnaire, of whom 2417 did not say yes to anything, while 875 said yes to at least one question. Follow up questions revealed that only 36 were actually trafficked, of whom 16 were sexually trafficked. This implies that of the 4% who said yes, only 1.7% actually were trafficked at any point in their life.

And yet, when you look at what the study uses, they don’t use those numbers. Instead, they say the percentage of people who answer yes to at least one question and are actually trafficked is 76%. What? Where did they get that number from? Well, you’re probably not going to believe it, and you’re definitely not going to like it.

The study whose numbers they use got their sample from a survey of homeless youths between 18 and 22 who have entered a shelter. Dare I suggest – is it conceivable? – is it possible? – that homeless youths might differ in their likelihood of being trafficked from the general population? In the general population, 1.7% of people who answered yes to question 3 turned out to actually be sexually trafficked in the E.R. study, while 86% of youths who answered yes turn out to be in a New Jersey homeless shelter. The authors in the Florida study, because they are incompetent hacks, manage to get the numbers flipped, but it wouldn’t improve a thing if they corrected it.

But that’s not all!! They report victimization as a flow, as a number of victims per year, but the E.R. study is asking about lifetime victimization. Adjusting for this would actually be extremely fiddly, but it would cause the number of people who are actually trafficked per year to plummet. Remember, across the entire nation, there are fewer than a thousand cases of sexual trafficking brought per year. These cases involve many things which we would not normally describe as sexual trafficking – federal law includes someone taking photos as sex trafficking – and some of them involve bog-standard prostitution across state lines, but it is a much sounder basis that reporting a survey validated using a wildly different sample than what you have surveyed.

My contention is simple: if you believe that a survey of homeless youth tells you about the accuracy of a screening measure when applied to the general population, and a survey which actually screened the general public does not, then you can accept the paper. Otherwise, you must reject it.

Here are the facts, as far as we can tell. There is a statewide non-profit, the Florida Council Against Sexual Violence, which aggregates data from their 26 centers across the state, found 158 victims. Prof. Reid’s team reports this in their paper. It is not their preferred estimate. Ah, well.

The errors in the paper go far beyond mistakes. They are so blatantly improper that it boggles the mind for them to be anything other than deliberate deception. So, to Prof. Joan Reid of the University of South Florida, you are a dishonest, malignant hack. I would rather die than have my name attached to the articles you write.

To Mr. Witker: you have been taken for a ride. It is not the case, as you have argued on twitter, that some number is better than no number – not when that number is in practice made up. You should retract the article, and learn how to evaluate studies. In particular, you should not be concerned with the result, so much as you should be concerned with the methodology. If the methodology is good, then, and only then, should the study be cited.

To Prof. Haidt: you are a public figure of considerable influence. Your work has been read by millions of people. What you say and endorse shapes the public’s perception. When you publish work that is totally detached from empirical reality and good research norms, you are making the world worse. It is incumbent upon you to do better.

Forceful as always. If only we were allowed to write our academic Econ papers with such powerful language ... Imagine the debates.

The first question describes many taxi drivers or people working with dangerous tools at factories. Actually, if we read the question literally, "Have you ever worked or *done other things* in a place that made you feel scared or unsafe", it's basically asking if you have ever been to any scary place in your life and done anything at all there.

The second is most relevant to slavery, but makes no mention of sex. The third also counts voluntary prostitution and women with sugar daddy boyfriends. The fourth probably covers a wide variety of situations; for one, it includes about all professional criminals.

And I don't get why are we using the word "trafficking" to refer to all sexual slavery, including the people who are enslaved locally and not shipped anywhere.