Heblich, Redding, and Voth are Wrong!

Why “Slavery and the Industrial Revolution” severely overestimates the macroeconomic benefits

Heblich, Redding, and Voth’s “Slavery and the Industrial Revolution” (2022) is a wonderful paper, with one very wrong section. They wish to measure the impact of slave ownership on the Industrial Revolution, and are able to find the local impacts with clever, well-identified, and sound econometric methods. This part I have no dispute with, and indeed congratulate the authors, and thank them for their contributions. In section 6, however, they go badly wrong. They wish to find the impacts of slave ownership on the Industrial Revolution as a whole, but I do not believe they have grounds to make the claims they do.

Let’s go over what the paper does do. You cannot simply regress slave ownership rates in areas with the level or rate of industrialization because of confounding – areas that were wealthier beforehand, for example, would be more likely to both own more slaves and industrialize sooner. You need some source of exogeneity – something random or quasi-random – to isolate the effect of slave-owning per se on industrialization.

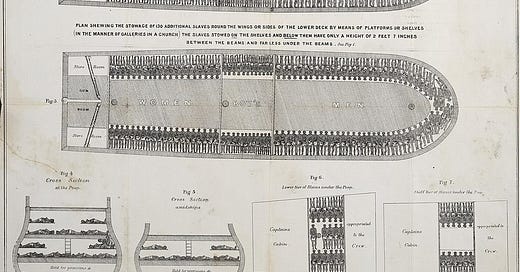

They take as given that the time it took to cross the Atlantic was essentially random. Sometimes you have terrible luck with the wind, other times you have good luck, and this luck is unrelated to the investors in a particular ship. If the ship was faster to cross the Atlantic, it was more profitable (for the rather grisly reason that fewer of the slaves died). Investors who had better luck on the first trip across were likely to reinvest this wealth into additional slave trading and slaveowning, while those with bad luck grew discouraged and left the sphere of investment.

The authors then tie the individual investors using genealogical data to particular 9 km hexagons covering the entirety of Britain, and obtain the number of slaves owned from the compensation act of 1833 (which abolished slavery). This can then be compared to a map of industrial establishments, share of labor force in manufacturing, etc. They find that “a one standard deviation increase in compensation payments translates into a 0.84 standard deviation increase in rateable values, a 0.75 standard deviation decrease in agricultural employment, a 0.90 standard deviation increase in manufacturing employment and a 0.62/0.83 standard deviation increase in the number of cotton mills in 1788 and 1839, respectively.” (p. 32) At the same time, the areas which did not have access to slavery investment contracted, with “a decline in aggregate income of -1.58 percent, a fall of population of 1.97 percent, a drop in capitalist income of 2.55 percent, and little change in landlord income”. (p. 39) They argue that this is due to access to slave investments increasing the return to capital such that more total is invested, and that the increase in capital accumulated led to more local investment and thus industrialization.

The macro results find that it increased British GDP by the equivalent of a decade of growth. These results are, however, dependent on access to slave investments increasing the amount of capital available. I will argue that their approach to calculating the profits from slaveowning overstates the aggregate effects. They take all other prices as given, and then simulating the cost of investing in slavery rising to infinity. A world without slave investments, however, is not one where everything would remain equal — we have good reason to believe it would akin to a large tax cut.

The sugar colonies were not free – protecting them from other European powers was extremely expensive. The Royal Navy cost 1,125,000 pounds a year during peacetime between 1715 and 1739 (Baugh, 2015) – a figure increasing to 2,500,000 pounds during war time. Adjusted to constant 2013 pounds, that’s 135 million and 300 million pounds, at a time when total British GDP was around 9 billion pounds. The Royal Navy was 3.3% of total GDP – and the high-end estimates of the profits from slave owning are 5% of GDP. This does not even take into account the troops which had to be garrisoned on the islands. By the 1700s, the British stationed 3 to 7 regiments of troops in the West Indies, at the cost of 115,000 pounds annually, and at least 19 ships, at a minimum cost (including the cost of men alone) of 315,895 pounds. (Thomas 1968). Of course, Britain would doubtless have had a navy without the colonies. We cannot simply deduct one from the other. But they doubtless would have had a smaller navy, and we must include the cost of providing it in our estimates of social gain.

We still have to deal with the problem of the sugar tariffs. Britons were barred from buying foreign sugars by the high tariffs on foreign sugar. If the profits to plantation owners are coming from taxes, then the discouraging effects of taxes on savings must be taken into account too. If we granted a monopoly to an oil company, it would be inappropriate to describe the profits of that company as benefiting the nation on the whole, without taking into account the high costs paid by the ordinary consumer. One must consider opportunity cost.

There has been work into quantifying the cost of the sugar tariff by R. P. Thomas, 1968 — between 1759 and 1762, the islands of Martinique and Guadalupe fell into the hands of the British. While they were French colonies before, they could now export to Britain on the same terms as the other British colonies. The price of sugar fell dramatically, indicating that Britain needn’t pay as much as they did. The price of sugar was consistently lower — about 33% lower — in Nantes as compared to England. This makes the accumulation of capital due to slavery less of a real accumulation, and more of a transfer within income.

Now, can it be rescued? I think you could make some arguments — perhaps Britain, in the absence of colonies, would have spent just as much as it did on the military. You can also argue that the change in the short run price of sugar when Martinique and Guadelupe were captured is much greater than the long run price, and so we are overstating the cost of the tariff.

Reasonable counterarguments they are, but they do not change the sign on the effects. The benefits to Britain must be overestimated, and most likely overestimated by quite a bit. We should be more skeptical that the sugar colonies were, in fact, beneficial to Britain.

Sources:

Daniel Baugh, « Parliament, Naval Spending and the Public », Histoire & mesure, XXX-2 | 2015, 23-50.

Heblich, Redding, and Voth, Slavery and the British Industrial Revolution. 2022

THOMAS, R.P. (1968), The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire:Profit or Loss for Great Britain?. The Economic History Review, 21: 30-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.1968.tb01000.x