Marta Prato is one of the most exciting young talents in economics, and has been involved with a number of extremely good papers. Her work is on the sources of innovation, and what we can do to encourage it. Her job market paper, and best paper by far, was “The Global Race for Talent”, which has recently been published in the QJE. Researchers are an extremely mobile population, as any country would be happy to have them. Prior research found that they are quite responsive to tax rates, and will relocate for efficiency gains others won’t take advantage of. The two principal places an inventor might relocate to is America and the European Union, so she looks at what happens when they do move.

She finds that most people move from the EU to the United States. The most striking finding is that, not only does moving to another country increase patent application per year by 42%, it also increases the patent applications of the people who stayed behind. This effect is for both directions – the people who move from America to the EU are pursuing an opportunity which really does raise their productivity. Strikingly, since ideas can diffuse from one market to another, the EU preventing “brain drain” might increase its well-being in the short run, but would lead to lower incomes everywhere in the long-run. That is not even taking into account the effect that it might have on later decisions on whether to become a researcher or not, since her model assumes that workers are exogenously sorted into production or inventing.

This ties into a broader literature disambiguating trade from openness. What economists want, when we call for free trade, is not an excessively literal exchange of finished goods, but a bundle of related things which improve the diffusion of ideas. People moving is a key part of dispersing knowledge. We should expect the gains from immigration to be larger than would seem obvious – we’re not very good at picking up why, exactly, an idea was transmitted. Andres Rodriguez-Clare attempted to put some numbers on this, and came up with frictionless trade in final goods adding 13-24%, and openness tripling output.

Prato, with Akcigit and Jeremy Pearce, has studied how a government which wants to increase innovation can do it most efficiently. In an idealized world, the only thing which matters are subsidies, and it does not matter what form it takes. Ideas require a fixed cost to find, and are underproduced because competition keeps the price below what is needed to find the ideas. It shouldn’t matter, then if we subsidize R&D, or make it cheaper for people to discover ideas.

In the presence of frictions and departures from that simple world, however, the form of R&D subsidy matters. Using data from a Danish program to boost innovation and education, they found that, in the short run, direct subsidies to R&D were most effective. However, in the long run, subsidies to education are more effective. The optimal policy involves both shaping the skills which people have, and then pulling them into specifically research work.

The most similar work to this is “Who Becomes an Inventor In America”, which argues that exposure to people doing innovation is a surprisingly important determinant of who later becomes an inventor. Two children with the same objective ability as measured by test scores will have very different outcomes depending on their neighborhood or their family. The natural extension is to consider how segregation by income has changed in the United States over time. In “The End of the American Dream?”, she, with Alessandra Fogli, Veronica Guerrieri, and Mark Ponder show how rising inequality leads to increased segregation by income, and how this (due to differences in the return to education in different neighborhoods) leads to the talent of poor students being wasted. No one has, to my knowledge, combined these two strands, but the natural implication is that residential segregation reduces innovation. With the same co-authors, she considers what the effect would be if “Moving to Opportunity” were scaled up nationally. Moving to Opportunity, by the way, was a big program to pay randomly assigned families to move to different neighborhoods, some of whom were constrained to move only to richer neighborhoods. They get the micro estimates from Chetty-Hendren – what they find is that, if it were scaled up, the gains will attenuate. People moving will make the place they move to a bit more like their own. A place-based transfer, instead of prescribing moving, reduces the gain to the poor group but actually increases total welfare gains.

The model they use is fairly similar to her work with Josh Morris-Levenson called “The Origins of Regional Specialization”. In “The End of the American Dream?”, they have a two-period model where the ability of children is correlated with that of their parents, and so high and low ability parents assortatively marry, and move to high and low skill sections of town. Here, moving is costly and there are increasing returns to scale due to agglomeration. The natural result is that some states specialize in some sectors over others, and people only move if they receive an unusually high enough level of skill in a trade which makes it worth moving. Their prediction, which they validate with census data, is that sectors which expand employment in a given state tend to hire more interstate migrants, and that those migrants switch sectors at a higher rate.

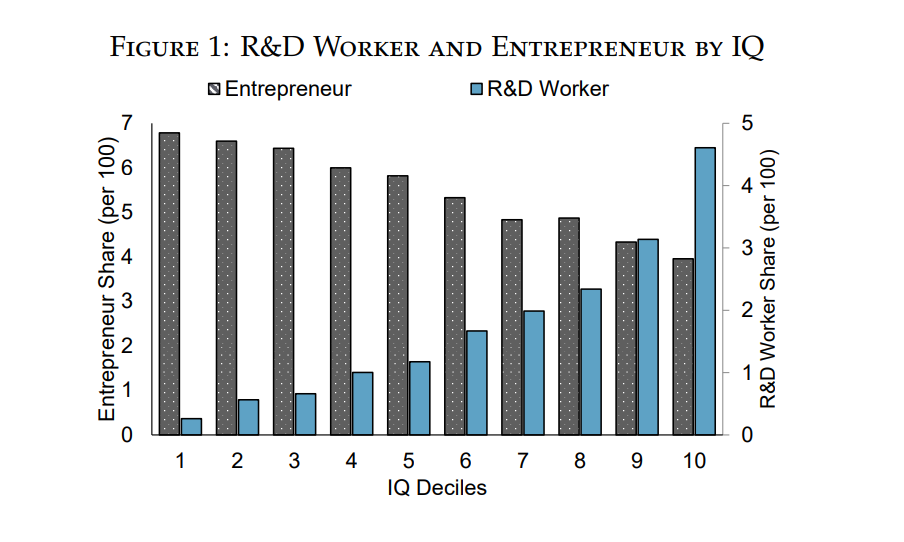

Another paper, “Transformative and Subsistence Entrepreneurs”, with Ufuk Akcigit, Harun Alp, and Jeremy Pearce, is interesting mainly for how it implies that raw measures of business creation can be misleading if the reasons why people are making a business changes. Most small businesses are meaningfully trying to change the world – they are just trying to start a lifestyle business, and being their own boss is just an idiosyncratic corporate structure. Most small businesses are things like real estate agents and shopkeepers, not tech startups, as Hurst and Pugsley (2011) document. Her paper is building on Akcigit’s other work on the influence of IQ in what people create (though using Danish instead of Finnish data, this time), and finds that, perhaps surprisingly, lower IQ people are actually more likely to be an entrepreneur than high IQ people. They believe that this trades off against choosing to work in research and development, which is quite strongly correlated with IQ. In a mirror of “Who Becomes an Inventor in America”, they find that having entrepreneurs in the family increases the likelihood of being an entrepreneur.

So how can we separate out the tech founders from the shop clerks? If you define a “transformative” entrepreneur as a company which has hired at least one R&D worker, then the correlations of IQ and education flip. Transformative entrepreneurs are much more intelligent, and their companies grow by more and faster.

They then look at what the effects of financial frictions on educational choice, and find that subsidizing higher education is incredibly effective. With a budget of .05% of GDP, education subsidies increase innovation by 16%, against an increase of 0.1% for entrepreneurs generally. The government does a lot to support small businesses now, but these subsidies are extraordinarily misdirected. At no budget is a general subsidy for even business creation good, much less our present subsidies for small business.

One of her works-in-progress is on the geography of innovative firms – given that one of her co-authors recently had an extremely exciting paper on separating out the causes of city wage premiums, I am looking forward to it. That paper found that much of the apparent agglomeration effects are actually from the most productive firms sorting. Yes, there are agglomeration economies, but they are much smaller than they would appear from mere correlations.

I came away extremely impressed with her work. It is earnestly and seriously trying to answer very important questions, and it does it extremely well. I am excited to see what comes next.

The Trump Administration seems to have studied this paper carefully in order to do the opposite. :)

This is an interesting piece from Nicholas. I will have to read this paper, but I am always looking for ways to maximize the creation and dispersion of knowledge.

I just completed Bryan Caplan’s book, The Case Against Education (essay coming on this soon), and I find it persuasive that higher education is, for the most part, broken in the US.

I previously suggested that if we finance higher education using income-sharing agreements, we might better align the incentives of industry, businesses, and universities.

Now I am also wondering if we paired this with additional subsidies to research universities, we may unlock a new level of innovativeness.