Kremer Patent Auctions

How to get allocative efficiency without harming innovation

Readers of this blog may already know that I love Michael Kremer. Some of the readers of this blog may actually be Michael Kremer. If so — big fan, love your work. Patent auctions in pharmaceuticals are an idea of his that I love, although I am concerned that practical difficulties may make them unfeasible. Let’s learn about them!

i. Patents and why we have them

Patents exist to give supernormal profits to the inventor of an idea. Since they’re the only seller of a particular drug, they can price above where they could price if there were competing firms. Since we assume they sell only at one price, in order to increase their profits they must constrain the quantity which they sell. Granting them some degree of price discrimination reduces the distortion, but does not eliminate it. I have covered in a previous blog post why a patent is insufficient for generating the socially optimal level of inventions; but it’s also really bad at getting the socially optimal level of goods produced.

How do we get both productive efficiency, and incentivize finding inventions? If the government could calculate the value and buy the patent for that, they could put it in the public domain, and make it like a generic drug. Of course, it’s really hard for the government to know what the value of a patent is, but it is something which pharmaceutical companies should have a pretty good idea of.

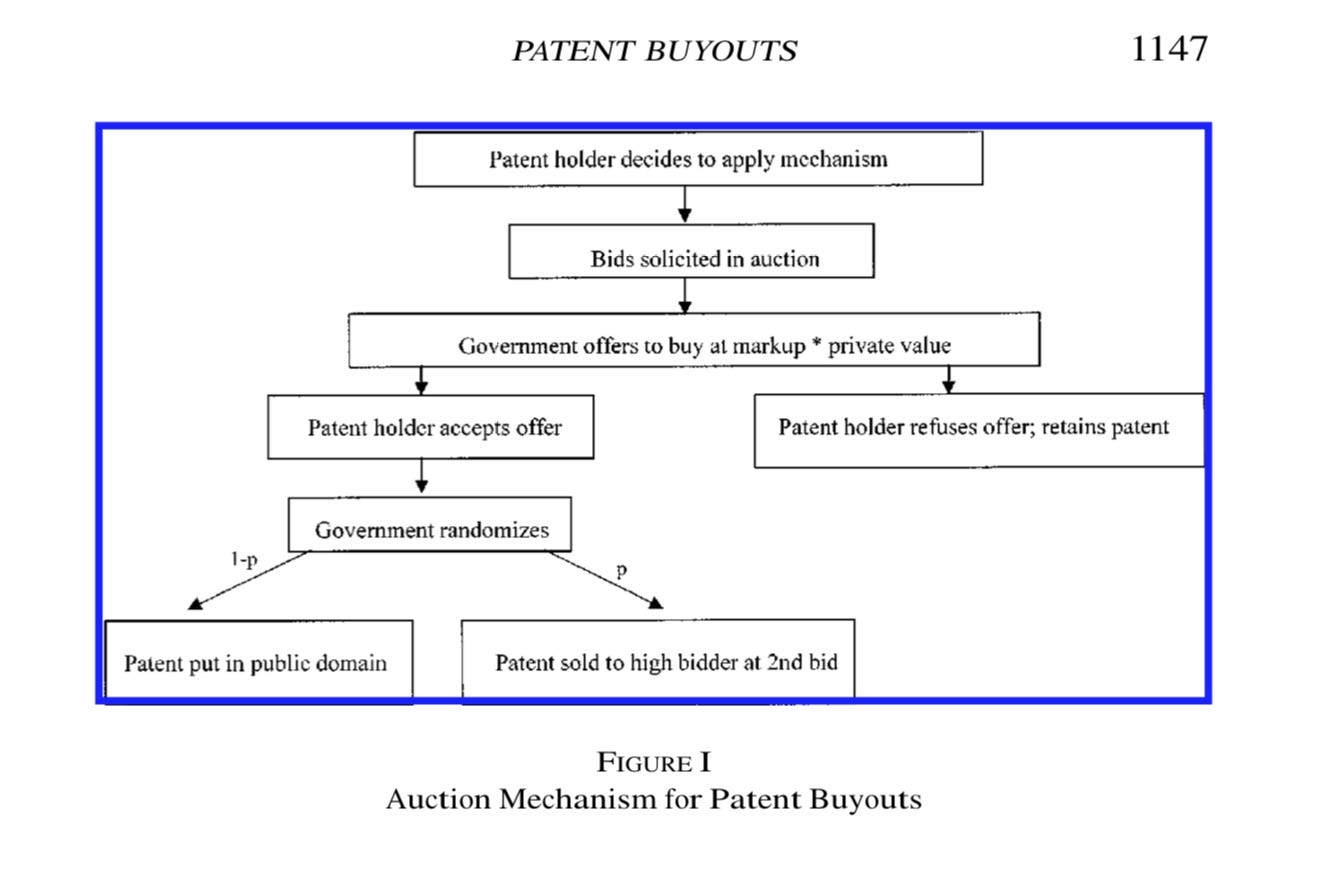

When someone files a patent, they can put it up for auction. This can be either mandatory, or voluntary (Kremer favors the latter in the original paper. I have come around to it being the latter.). Everyone in the world can bid on the patent, in a normal second price auction. Some percentage of the time, the highest bidder wins. The rest of the time, the government buys the patent at that price plus a percentage, and puts it in the public domain. Thus inventors get fully compensated, and we’re able to produce optimal quantities. Alternatively, if it is made mandatory, no markup is needed. Kremer helpfully includes a flowchart of the procedure.

The reason why there must be a mark-up is a sort of “no trade” theorem, along the lines of Akerlof, 1970. Companies have private information about how valuable their patent is. Offering to sell at a given price indicates that they might have information making the patent less valuable than it would seem. You might want to sell, rather than lease, the rights to produce the drug if the investments needed are quite specific, ala Klein, Crawford, and Alchian 1979. If you pay a flat fee for someone to manufacture your drug, then the manufacturer could claim that they ran into “unforeseeable difficulties” and need more money to get it done. If you get around this by having them sell the drug, and you get paid a fee, you would certainly have to promise not to lease the rights to manufacture the drug to anyone else during the period. (This is adjacent to Coase 1972 — anyone who has sold the profit maximizing quantity still has the ability to sell a little more later, and knowing this, people won’t be tricked into buying for the monopoly price). Offering a markup makes it reasonable that someone would sell it for reasons beyond it being a dud.

Having it be mandatory would get rid of the need for a markup. It would not do for two reasons. First is that if anything, we should pay awards on top of the patent system, but more importantly is the interaction with multiple patents which function together. I have stuck with pharmaceuticals thus far, as they are one of the clearest areas where patents are effective, but let’s imagine that this applied to all patents. If someone patents many parts within a smartphone, none of which are particularly valuable separately, then releasing some parts into the public domain isn’t valuable; and bidders would have no incentive to place bids at all which remotely reflect the combined value of them. If the patents are only on particular drugs, then it should be all right — but anyway, there’s a much bigger problem.

ii. Collusion

The basic idea is good, but I am extremely concerned about collusion. Imagine a company puts up a valueless patent. Subsidiaries of the company offer to buy it at outrageous prices. If the government doesn’t buy it, then they’re just shuffling money between themselves. Obviously, the government must ban someone bidding on their own patents. This is tricky though! Many firms are owned in large part by the same mutual funds. Are they subsidiaries? Can you really ban most major pharmaceutical companies from bidding? The number of companies which can credibly bid for some of the big patents is quite small anyway. They could arrange between themselves to help each other — you bid for my drugs, I bid for yours. Read Klemperer 2002 for many amusing examples of how insufficient care in auction design (say, selling five licenses at auction when there are five incumbent firms) leads to faceplants.

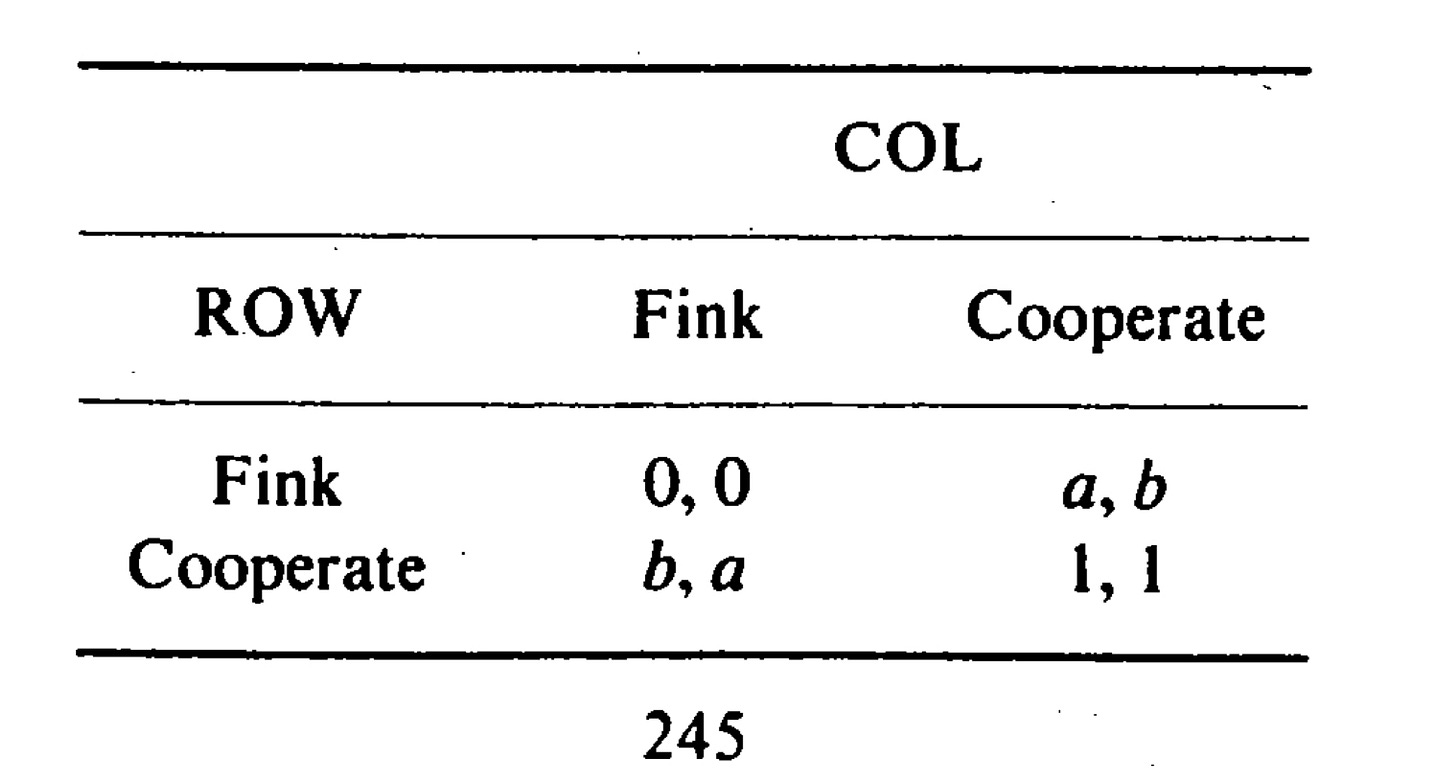

So let’s suppose we ban communication. In a game with sufficient rounds, cooperation can be sustained. Kreps, Milgrom, Roberts, and Wilson 1982 give bounds on cooperation in a game with the following form:

The only Nash equilibrium — that is, any equilibrium where neither player can improve by unilateral action — is at 0,0, with both players defecting. You can reach this by backwards induction — in the last round, it is strictly better for you to defect if the other is cooperating, and so in the next to last round, it’s better to defect, and so on and so on. If both players assign the other some probability that they will not play this perfectly rational and maximizing strategy, however, then cooperation can be sustained with a tit-for-tat strategy. If we assign the probability that the players play cooperatively the variable ð, then the number of rounds needed for cooperation is given by (2a-4b+2ð)/ð. Besides that, since players are uncertain about the total number of rounds, the game might not be finite anyway. When people are unsure about how many rounds there are, they cannot backwards induct, and so it does not become dominant to defect. Companies could overpay for their competitors, knowing that they will get rewarded in another round.

Kremer suggests taking into account the full distribution of bids as to patents value, and determining the amount to be paid as some amount times the, say, third-highest bid. This will make the auction slightly more robust to collusion, but really not by much. You’re still not getting around the fact that there are very few firms willing to put $25 billion for a pharmaceutical patent, they’re all going to know each other, and it would benefit all of them to try and suck the government dry. He suggests multiple methods of dealing with collusion on page 23 (section vii). All of them would certainly mitigate the problem, but I am not as confident as he is.

So, it seems like we’ll always have some imprecision about the value of patents. Nevertheless, any subsidy to research in pharmaceuticals — really any at all — would be good. The social value really is just that much larger. Kremer says it best. “Collusion itself is not a problem; deadweight losses due to collusion are a problem, and there is little reason to think these deadweight losses would exceed the deadweight losses due to insufficient original research, monopoly-price distortions, and the diversion of effort to “me-too” research in the absence of patent buyouts. Even if collusion raises prices above their social value, the social value of inventions may be approximated better by the collusive prices than the current patent system, under which private incentives for developing new inventions are likely to be less than half the social value of the inventions.” (p. 26-7) I agree totally.