Misallocation is Missing the Point

What is convenient to measure is not the most important stuff

We would like, of course, for poor countries to be richer than they are now. Ultimately the only way that anything is going to improve is for them to produce things with greater efficiency than they do now. A lot of the literature on global poverty focuses on misallocation of resources across firms, starting with Restuccia and Rogerson (2008), and, most influentially, Hsieh and Klenow (2009). Everyone agrees that there are bad laws which prevent capital and labor from going to the best firms. How important is this?

It’s Hsieh and Klenow that I’ll be mainly focusing on. Suppose that output is a function of a firm’s capital and labor, with each firm having constant returns to scale. The production function is Cobb-Douglas, so capital multiplies labor, and the whole thing is multiplied by a term representing total factor productivity. There is an optimal ratio of capital and labor, and as we get away from this, total output as a function of inputs falls. In Hsieh and Klenow, each firm faces a tax on their usage of capital and labor, which is subtracted from their inputs. The size of this tax – commonly referred to as a wedge due to the triangular shape of the deadweight loss – determines the importance of misallocation.

Hsieh and Klenow are not asking “how much would output rise if resources were perfectly allocated?”. That is beyond their ability to tell. They are holding inputs to an industry fixed, and only reassigning inputsThey also are not able to say what the perfect world usage of inputs within an industry is either. What they can instead do is compare industries to the United States, and ask, “If India were as misallocated as the United States, how much would output rise by?”. They find that output would rise somewhere between 40 and 60 percent.

Since then, there has been considerable disputation about the accuracy of the results. Everyone acknowledges that they are too high, we simply don’t agree about how much. First, measurement error will bias your measure of misallocation upwards. If there is zero misallocation, but you only get an error bar around the real level of output and input use, you will get an estimate of misallocation which is positive and increasing in the size of mismeasurement. Bils, Klenow, and Ruane (2020) hack about 20% off their headline figure by essentially subtracting out purely additive error, which will (as a percentage) not stay constant. Rotemberg and White note that the data the Census Bureau uses is extensively cleaned and checked for accuracy. With the raw data, they can apply the same procedures to both that and India’s data, and find that the misallocation is a mirage. In their original paper, the gains from ending misallocation were essentially zero. (I am not sure of the state of results in the latest drafts – the paper has kicked around for a while, but I think it’s sound). The original Hsieh and Klenow paper was not unconscious of the measurement error issue – they lopped off the 1% of firms on either end of measured productivity – but it was not enough.

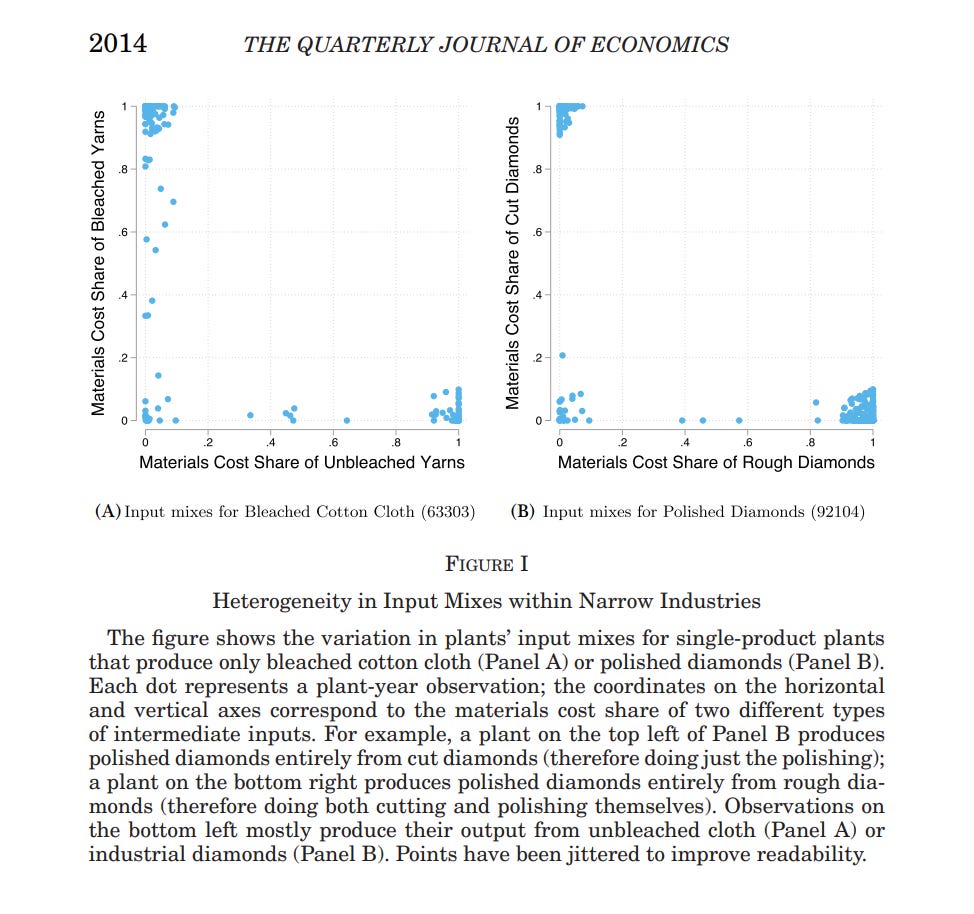

Second, we have to assume that firms within an industry all share a production function. Now, there has been some effort in separating out times when firms even within an industry classification do not use the same production function. Boehm and Oberfield (2020), who are measuring the impact of the court system on misallocation, estimate different production functions when the input mix is radically different – one would, as in the example below, not like to lump these two instances together.

Still, it doesn’t seem that even this can solve things entirely. Carillo, Donaldson, Pomeranz, and Singhal (2023), who, because they have access to truly exogenous demand shocks, don’t need to rely on the more indirect methods we have to use for the whole economy, found that actual misallocation was extremely small, even when measured misallocation was extremely large. Estimating production functions is actually just extremely hard, and we should be more cautious about doing it. (For more reading, see Nathan Miller’s write-up of the production function estimation literature.)

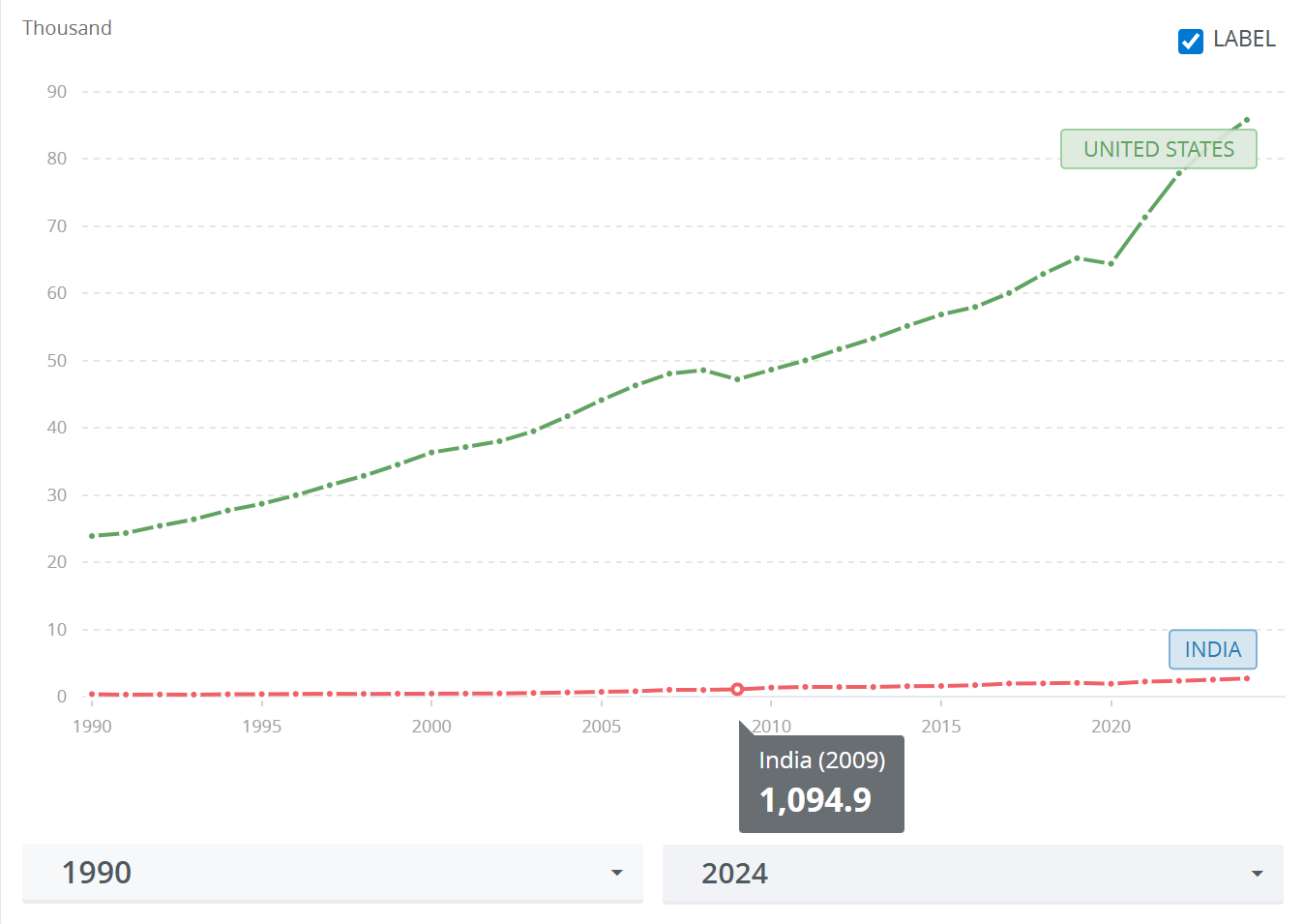

But all this is somewhat missing the point. We measure misallocation not because it is all that important, but because it is easy. What would happen if India perfectly allocated capital and labor across firms? Well, it would still be very poor, because India is not good at producing things. Even the highest of high end estimates, that manufacturing would be 60% higher in 2009 without misallocation, comes nowhere near the gap with the developed world.

Here’s India. Here’s the United States. If the same gains from correct allocation could be found across the entire economy, GDP per capita would go from about 1,000 dollars, to about 1,600 dollars. Just a thirtieth of the way there!

So what should we do to actually raise a country’s income? The thing is, we don’t really know. We have a sense that it’s good to have an intelligent country, working at low tax rates with an efficient government and responsive rule of law, to encourage the development of new technology and to not have bad regulations, and to allow for the free exchange of people, goods, and ideas; but these are all so obvious that it’s almost pointless to prove them over and over again, nor do we have any precise idea how large the effects will be. They are not implemented for reasons which are (largely) beyond the knowledge of economists, and so we feel that we don’t have much to contribute.

The things that are likely to solve misallocation are the things which would tend to make countries wealthier in general. As I have written about before, the courts in India are very bad. So too are the labor laws. So too are the restrictions on foreign ownership, and so too are the farm subsidies which keeps India one of the least urbanized large countries in the world. (65% of the country is rural, compared to 37% in China!) Changing these laws would be good, and they would likely reduce misallocation; but even more so, they would simply allow countries to grow.

Peter Drucker said that there is nothing as futile as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all. As a layman, that's the kind of misallocation I'd be looking at. Economic freedom indices are published by several sources, so the problem may not be as intractable as you think.

Taxes are a business input cost. What do businesses in different countries get back? The US spends a heck of a lot on defense, or war as it's more accurately called now. The US is also a top spender on education, with little to show for it. Businesses in EU countries spend twice as much on energy. The UK is spending more and more on what are said to be undeserving welfare recipients. That's the kind of misallocation that an economist working for a Formula One team would be looking at.