i. All the world a game, and we merely players

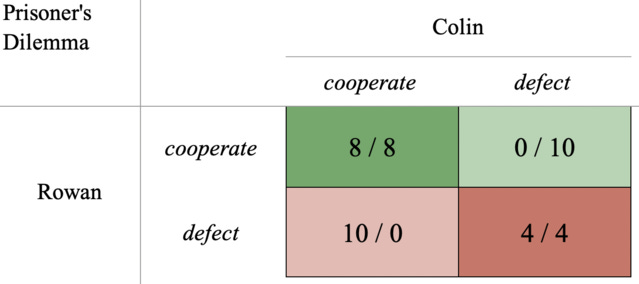

A prisoner’s dilemma game is where one player would gain if they defect, and the other cooperates, but both are worse off if both defect. We represent it using a matrix such as this:

The numbers are dollar rewards. If both players cooperate, they each get 8. They can defect to gain two dollars (at the expense of the other losing 10), but if they both defect, they’re worse off compared to if they both cooperated. There is only one Nash Equilibrium (where neither player benefits from unilaterally changing their strategy) at defect/defect, but it is clear that cooperate/cooperate is socially optimal. If we could trust each other to do the right thing, we would be much better off; but if each of us thinks the other will screw us, we are stuck in a bad equilibrium.

I believe choice in institutions is like this. Institutions can be thought of as the rules of the soccer game — the laws and customs and organization of a country can have an immense influence on how production can be done. Thus the poverty of developing nations is not merely a consequence of lack of skill interacting with a complicated production function, a la Kremer, but is also the result of poor institutions, which are themselves endogenous to the people’s attitudes and beliefs. "Do Institutions Cause Growth?" shows how places with high human capital come to develop better institutions. There’s a simple story here to tie it to the trust and patience of the people. For example, if you wish to have democracy, one must be willing to lose sometimes. You must believe that your loss is not permanent, or at least that the harms that will be visited upon you are not so severe as to warrant blowing up the system. In a world where every official is expected to be corrupt, you are a fool not to be; indeed, the person who doesn’t look out for their family is seen as the immoral one, not the bribe-taker. These bad outcomes can be incredibly persistent and self-fulfilling, as they remake cultural attitudes for the worse.

ii. The slave trade and other nasty things

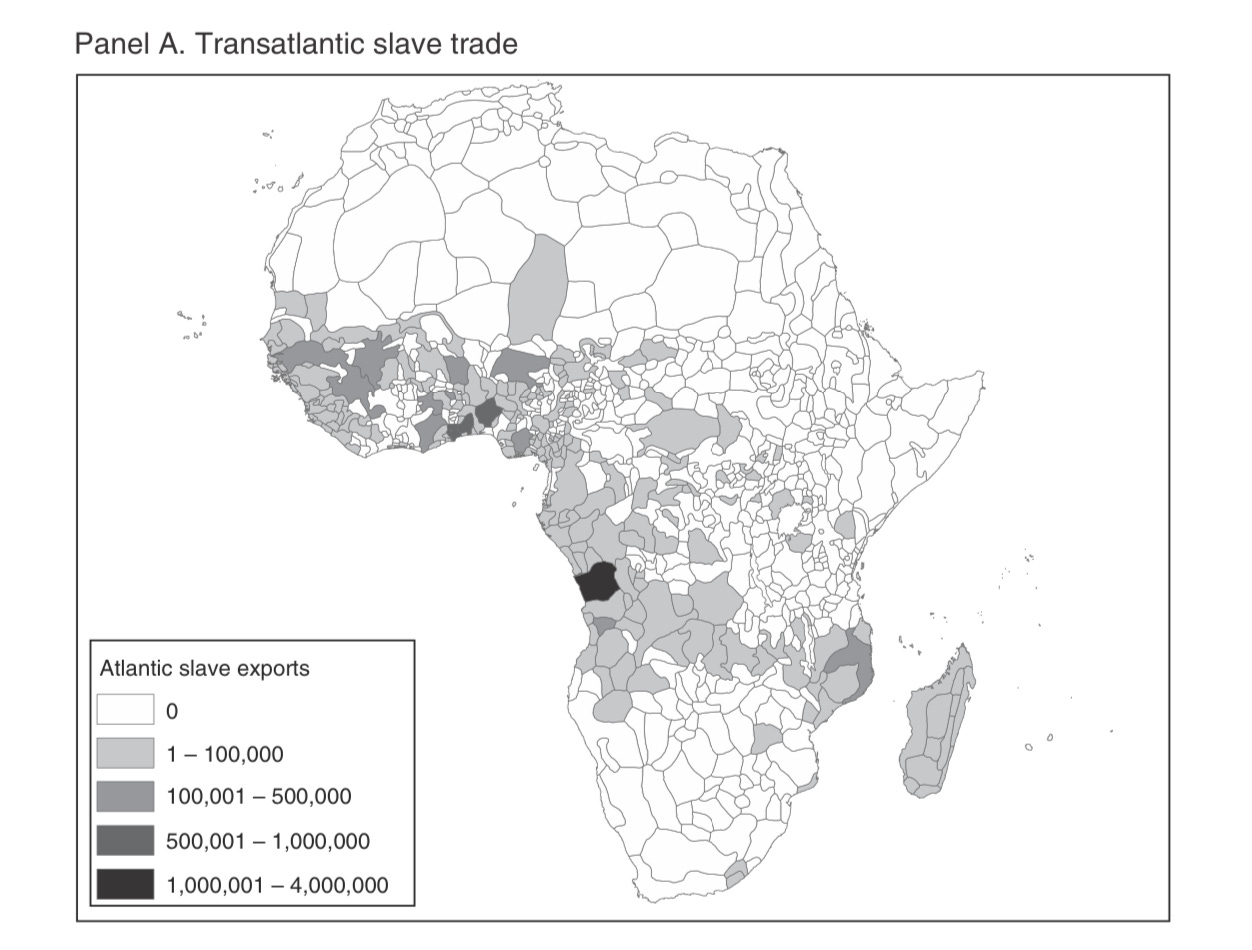

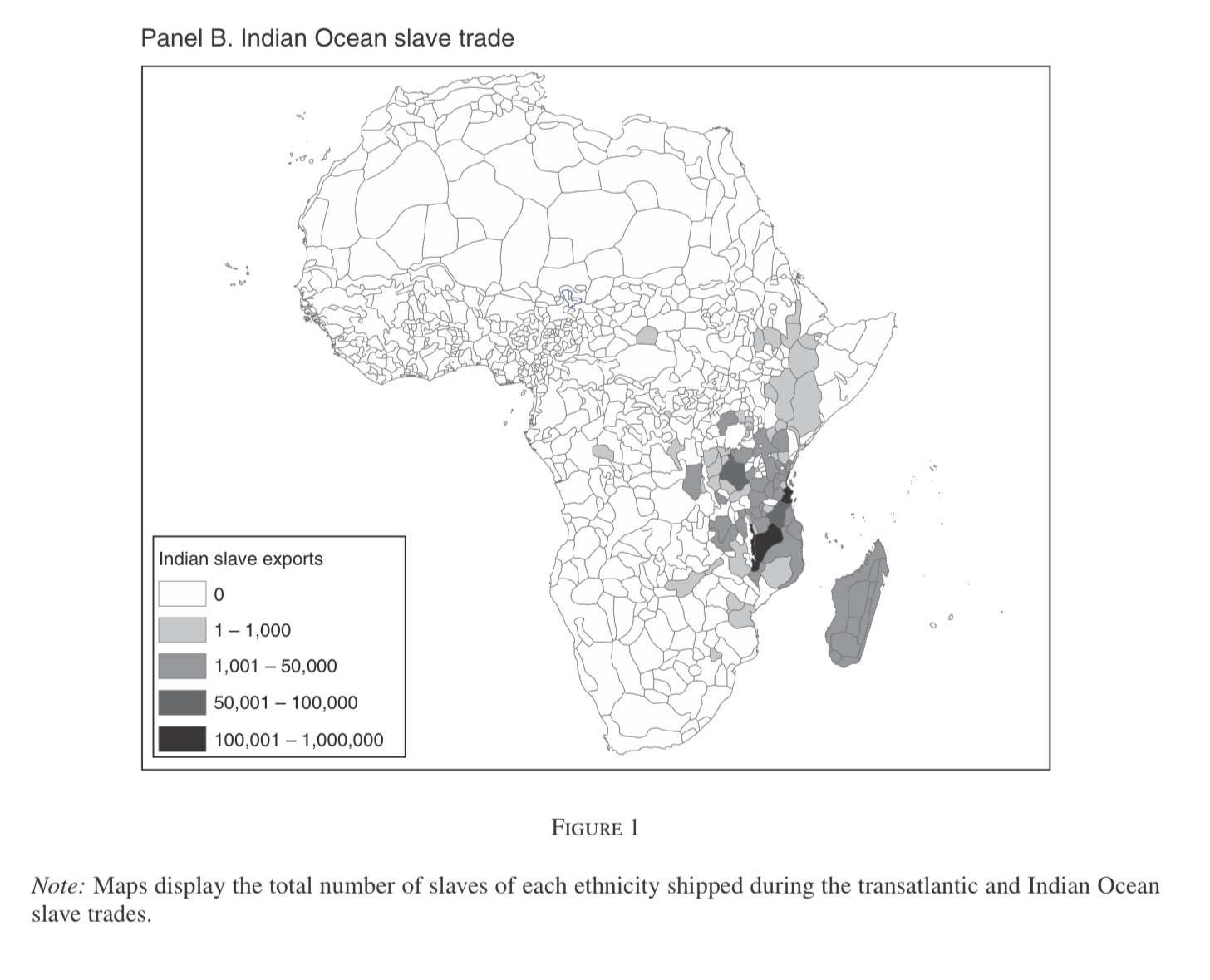

Nathan Nunn has a whole line of literature on the long run impacts of the slave trade on Africa; see here for the 2008 paper explaining underdevelopment, here (with Leonard Wantchekon) for the slave trade as the origin of mistrust in 2011, and here (with Diego Puga) in 2012 for a reversal of fortune, where rougher areas escaped the slave trade are unexpectedly better off now. He starts off in 2008 by estimating the number of slaves exported from each present day country in Africa (there are, by the way, close to complete records of all slave ship voyages from the Slave Voyage project. It is an extraordinary dataset. Consider writing a paper using it!) and connecting them with the port of exit. The cost of traveling to the coast serves to give us some plausibly exogenous variation. The slaves can be tied back to particular ethnicities from their name, or from it being written down at the time, or even from physical descriptions, and these ethnicities plotted using Murdock’s ethnic map. The places with relatively more slaves taken have worse outcomes. Nunn and Wantchekon extend the question to why this might be, and find that places which have more slaves taken have lower trust. What’s more, they have persistently lower trust – when people in ethnicities more affected by the slave trade migrate to other places, they are less trusting than their neighbors.

The figure here (from the 2011 paper) shows where the slaves were taken from. They did not particularly tend to be taken from more disorganized places. If anything, it was the opposite. The black square at the mouth of the Congo river is the Kongo kingdom, one of the largest kingdoms in Africa at that time. The increase in demand from the slave traders set village against village, badly fracturing the kingdom. In 1526 King Affonso (he converted to Christianity, hence the name) wrote to Portugal, complaining of how people everywhere, even nobles and members of the king’s family, were being kidnapped to be sold into slavery. The 2012 paper with Puga shows that the slave trade’s ill effects were so strong that it overcame bad geography. All else being equal, it’s cheapest to build infrastructure on flat land, and ethnic groups tend to be less fractionalized in non-rugged terrain. But, it is also easier to evade slavers in rugged areas, and this was important enough that rugged areas exposed to the slave trade do better now than open areas.

Ethnic fractionalization has been connected with poor outcomes. (See especially Easterly and Levine, 1997 for the finding, but also Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly 1999 for a theory why). It is underrated, however, that fractionalization is itself endogenous. The European nationalities which we see now as homogenous were not natural – they were made. The French did not speak French until they were made to by a centralized state. By the time of the French Revolution, only half the population could speak “French” (the northern language, the langue d'oil). By 1871, a quarter did not speak French as their native language. The nationalist movements of the 1800s were in part a movement to gain freedom for their country, but also a movement to create their country. As our economic status improves, our moral circle expands outward. We move from caring about kin, or perhaps tribe, to caring about our country (and if we are lucky) to caring about our region, and the world. I cannot say with any certainty the direction it goes — doubtless the two influence each other, or are affected simultaneously by other variables. There are, nevertheless, many bad policies which cannot be well enacted upon those in your moral circle. Slavery for one, but also trade barriers, or asking for bribes. One does not ask their kin for a bribe.

(Slavery, in my view, should be treated in terms of trade. Perhaps 1 in 10 or 1 in 11 slaves died in transport across the Atlantic. Why not enslave them there? That is, after all, what serfdom is – enslavement of the people where they are, rather than going overseas. If there are declining marginal returns to labor in agricultural production, then it is clarified – Africa, being land poor and relatively labor rich, will export labor to land rich and labor poor countries. What this renders troublesome is counterfactual estimates of Africa’s population in the absence of the slave trade. We can surely not assume an exponential rise in population, but we might not be able to assume any rise at all. If Africa was nearing a Malthusian equilibrium, then we should revise our counterfactual estimates down. We should look at the history of plantation agriculture within Africa for evidence. My understanding is that it became more common during the late 1800s and early 1900s, but that this is due to changes in production technology. Medicine (such as quinine) became better, allowing Europeans to settle to exploit Africans where they were. I do not know the history well enough to separate this out, and would welcome (informed!) comments on the matter.)

iii. So how do we get out?

We cannot expect places in a bad equilibrium to get out on their own. It most certainly has happened – how else to explain the rise from poverty of the developed world? – but it has not happened everywhere, and has taken a very long time in getting there. We are called upon to do something about poverty – but what to do? I believe it is possible for outside institutions to change the payoffs in the game, such that we can escape the bad equilibrium for the good.

The seemingly simplest way is to simply not let the country in a bad equilibrium choose their own institutions at all. Rather than have its own court system, you could require they instead use another’s. Brown, Cookson, and Heimer (2016) found that native reservations which have had state courts imposed upon them have better credit markets. People selecting into bad equilibriums can only happen if people are able to select institutions at all. Dippel 2014 considers times when reservations were formed out of multiple political groups. US policy was to not put totally disparate groups together – so they were at least always of the same language, more or less – but it was not always the case that they were meaningfully a “tribe” beforehand. One cannot just use assignment alone, because that could be endogenous. The instrumental variable of choice is mineable resources nearby. That the land had minerals was of no value to the Native Americans, but it made the land much more valuable to the settlers, so the Native Americans found themselves squashed on smaller plots of land. Groups which had no common history found themselves having to cohabitate. The crucial result of the paper, however, is that there was no divergence in outcomes so long as the US government was running things. It was only after the Bureau of Indian Affairs reduced its influence in the 1980s that the reservations diverged – those with more politically homogeneous groups were more prosperous than those with a history of division. Dippel argues that this is because the heterogeneous groups had more political conflicts, and shows that there are considerably more news stories about corruption and political scandals in the places with different groups. Governance is a game; you get to the best outcomes if everyone trusts, and cooperates. But it is a game which can be avoided entirely, if another country lends its institutions. Islands are better off today the longer they had been under colonial influence. Feyrer and Sacerdote used a dataset of tides and wind patterns to find which islands would be exogenously harder to get to than others. The longer they were governed, the better they are doing today.

It does not have to be done with the stick, but can also be done with the carrot. After the breakup of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Warsaw Pact, some countries expected to be admitted to the EU, while others did not. Those countries, such as Poland, which expected to be admitted to the EU knew that for that to happen, they would need to reduce their level of corruption. Poland’s anti-corruption campaign was successful – by 1997, they had far lower levels of corruption than Russia and Ukraine. In fact, all non-USSR countries in this study had far lower levels of corruption. The important thing is that it did not take the EU crossing the border and marching on Warsaw — all that was needed was to make it profitable to crack down on corruption.

If we want to get rid of dictators, then we may need to offer them asylum in exchange for leaving. Everyone wants retribution, certainly, but as a cornered animal fights to last, so will a dictator. Rather than allow a place to enter a civil war, we instead offer the weaker asylum safe passage to America. I think this would be a great improvement over the status quo. How long will there be anarchy in Haiti if we offered the gangs asylum in the United States? Why squabble over dross in Haiti?

iv. What were the effects of colonization?

Having political decisions dictated by outside forces is certainly a violation of sovereignty. It is not clear that that is colonialism — or put alternately, that colonialism so vacuously defined is bad. It is still a relevant critique of the idea that we in the developed world should impose better institutions that the track record of colonialism is not very good!

But we should be clear about what we mean by colonialism. It is misleading to compare expeditions of plunder with humanitarian interventions — that France colonized it in the 1700s does not mean that a United States mission to restore order now would be morally equivalent! It would be too much a “no true scotsman” fallacy, however, to exclude all cases but a very few. I would thus include British colonization in the later parts of the 1800s, where there were genuine ambitions to reform and improve society. (The EIC depredations had no such ambitions). I would include the French colonizations as well, but alas I know close to nothing of the literature on the topic. It is generally agreed that the British were the best of the colonizers, the Germans, Belgians, and Japanese the worst, the Spanish very bad, the Dutch quite bad, and the French altogether bad.

Countries which were outright settled had far better outcomes than those which were ruled indirectly by an avaricious few. The shakiness of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson, 2001’s evidence has not convinced me that the basic idea is false. Places more hospitable to settlement saw more settlers, who set up long-lasting institutions which changed things for the better. The criticism of Glaeser et al. (2004), that it is actually human capital all the way down, is reasonable and possibly true, but the AJR thesis can be rescued by noting that migration is not random, and perhaps groups with higher human capital were more likely to migrate to lower risk places. (The voyager to Meso-America could find gold, or they could die of fever. The pilgrim to Boston would not find riches, but neither would they find tropical fever). Positive effects tend to become apparent in the long run, and may be through other channels than institutions per se. Puerto Rico, were it a country, would be the richest country by any measure in all of Latin America, but it is not clear whether that is due to the United States having a directly positive effect on institutions, rather than immigration being really good. (You are doubtless familiar with my views on immigration — I favor open borders with the world, and incidentally believe that this will improve institutions in poor countries. The question we are examining, however, is the merits of directly imposing new institutions. I would also consider the legacy of changing the lingua franca to English to be an unforeseeable benefit, and not something to rely upon).

Any literature review is necessarily speculative — we do not know what the counterfactual of no colonization is in almost all instances. Economists can turn to plausibly exogenous sources of variation, but we only have so many of those. These sorts of instrumental variables tend to not be robust to different specifications. Moreover, the questions they can answer are quite limited — we can reasonably find answers regarding the different administration of princely states in the British Raj, but would be ill-equipped to say what difference administration by the Dutch in Indonesia and the British in India made. Further, this is not a meta-analysis – we are not comparing like things, and so when studies for and against the proposition are made, it is, to some degree, uninterpretable. Nevertheless, I will tell you what I know of British colonization.

The effect of the British on India is mixed to negative. I emphatically reject the notion that the British caused an increase in the rate of famines. Rather, the British kept more and better records, and picked up on famines that would have otherwise have disappeared from history. (I cannot seriously believe that there were no major famines between the 1630-32 Deccan famine and British rule). The expansion of the railroads substantially increased income and basically ended the recurrent famines (Donaldson’s “Railroads of the Raj and the related “Railroads and the Demise of Famine“, with Burgess). Save for the war-caused 1943 Bengal famine, there were no serious famines between 1900 and independence. It did leave India with worse land owning institutions, which diverged during the Green Revolution in the 1960s. (Iyer 2010, Banerjee and Iyer 2005) Places under direct rule tended to have landlords, controlling smaller areas of land each, and while they had similar literacy rates they had lower levels of infrastructure investment. Iyer’s analysis is extended with night-light data to more directly measure GDP, and places under direct rule have a much slower rate of growth. (Jha and Talathi, 2021) Kapur and Kim, 2006 disagree, on the grounds that the non-landlord regions were doing better all along. They are arguing for there being a violation of the exclusion restriction — coming under direct British administration was, in fact, correlated with preexisting poverty. The British had a policy of free trade for colonies since 1846, when they dropped any requirement that colonies favor their own goods.

In terms of the formal government Britain left behind, I’d have to say it has been fairly good. The Nehru-Gandhi family became autocratic, but in spite of everything India has been generally democratic — especially surprising given how poor it is. Pakistan has done considerably worse, though, with periods of military rule between 1958-71, 1977-88 and 1999-2007. Bangladesh (which was formerly East Pakistan) separated from Pakistan in 1971, but did not democratize until 1991. The economic culture which Britain left behind was terrible – I have half-joked that the worst thing Britain ever did was educate their economists at Cambridge – but socialism was in vogue in post-colonial countries everywhere.

In Africa, things were considerably worse. The British ruled indirectly, turning group against group. Only in the rare places which they settled in — South Africa, for example — have economic outcomes been tolerable. Still, the British seem to have been marginally better than the French. Largely on account of the deplorable disease environment, the Europeans did not settle, and did not leave behind strong institutions.

v. Summing up

A theme is that obviously good policies are still good, even if forced upon an unwilling nation. There is no doubt in my mind that the opening of Japan to trade by the Western powers was extremely good for the people of Japan, then and now. The forcing open of treaty ports in China had quite positive effects. If some power is able to push good policies onto another, then that is good.

The wealth and poverty of nations in the long run is ultimately determined by its human capital, and the rules under which human capital can operate. I believe that small differences are multiplied, first by a long production process, and then again by the choice of institutions. We know more about fixing the latter, so let us do our darndest to fix it. We must not be seduced by the ideal of national sovereignty, if such sovereignty means the suffering of millions. Some ideas are good, and others bad. It makes little difference who is responsible for implementing them.

The persistence of democracy in India to me is a marvel, and a puzzle. It was the first major nation to begin with Universal Adult Franchise. The poor and those in rural areas strongly assert their right to vote — even if they may not protest as strongly when they’re denied other rights.