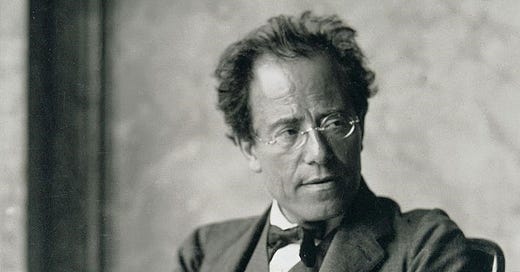

I don’t think there’s any composer who I’m more awestruck by than Gustav Mahler. I think it’s because I do not understand his algorithm for simplifying the process of composition — it seems to spring out in its optimal form, without being composed of distinct, tractable segments.

Many composers rely upon shorthands or forms to focus their composition. You can clearly divide many pieces into parts representing the harmony, and the melody — the composer can then work on the chords, and then work on the melody over top, or might illustrate a melody with harmony. They might create individual motifs, representing different characters or ideas perhaps, or even just melodic fragments, and set to writing music connecting the ideas together. Many composers compose at the piano, and think through the piano, and are ultimately limited (beyond the addition of a few flourishes) to what can be played at the piano. Mahler doesn’t seem to do that.

He writes music with nothing you can point to as being definitively the melody or the harmony. That is not to say he lacks them, or that he is totally unsingable, but rather that what is the “voice” of the piece passes seamlessly between multiple independent melodies which interlock without admitting alteration. There is this striking passage in the fourth movement of the sixth symphony, before the first hammerstrike, which is remembered as one seamless melody but is in fact the layering of four, independent, completely sensible, melody parts. No one else ever sounded like that, ever. No one had the knowledge and sheer ability to imagine it.

His music gives no indication of being reliant upon the piano. He wrote each symphony, essentially complete but with only rudimentary orchestration marks, on four staves. It cannot be played on fewer than two pianos. It seems he simply sat down and wrote it. The later orchestration is another matter. He was a conductor, known for his rehearsals and regarded as the best living by the 1900s, but even he has heard less orchestral music than the normal person today living with a phone in their pocket and a pair of headphones. He is in essence doing sound mixing without ever hearing what he has made until he steps up on the rostrum and raises his hands. Books of best practice existed, but he is doing original things. Imagining writing your code from imagination alone, without ever testing that it ran properly at any point partially through your process.

He did not write much, alas — some songs, perhaps 40 in number; one movement of a string quintet(fragmentary); a student cantata; a song-symphony; the nine symphonies (and an incomplete tenth). He worked slowly and only part time — the later symphonies were generally written over two summers each, while on vacation. It is a small legacy, by opus. But if we take as maximand the quality, the sublimity, the transcendent feelings and overwhelming joy of the average work, then there is not one who comes close.

What I really like about his music is the way he changes between moods so frequently without breaking the continuity of the music. The last movement of Das Lied von der Erde changes from sad passages to happy passages all the time, which gives it that kind of bittersweet nostalgic quality I rarely find in other composers.