Overestimating Climate Change Damages

Or in other words, short run elasticities are not the same as long run elasticities

It would seem that shock based estimates of climate change damage overstate the level of damages from climate change. To estimate damages from climate change, you can’t simply regress temperatures on GDP — both have been increasing throughout. Instead, you look for when the temperature was unexpectedly high, find the damages, and extrapolate. The trouble is that surely short run elasticities are lower than long run elasticities, and people are capable are far more adaption in the long run. A disaster expected is far less costly than a surprise disaster.

Consider — cold weather sure seems bad for your health. During times of the year which are colder, more people die. The important thing, though, is that it is *relative* coldness which matters most of all. Many of these deaths are from the flu or other seasonal respiratory diseases, which seem to occur in the relatively colder times of the year all over the world. Flu season isn’t worse in more consistently cold places, though, and if you simply extrapolate from colder weather equals more deaths, and don’t account for this being the flu, you will exaggerate the harms from cold weather per se.

Similarly, we would expect that in the short run people are badly affected by negative climatic shocks. They’ve chosen the level of adaptation appropriate for the average climate, and supposing this turns out to be off, they’ll be hurt. We wouldn’t expect, however, that they would never change their level of adaptation in the long run, as the climate changes.

This brings us to a recent working paper by Adrien Bilal of Harvard, and Diego Känzig, of Northwestern University, “The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Change: Global vs Local Temperature”. I wish to start my comments by first noting that it is a worthy and important paper. They are correct to focus on global, rather than local, temperature shocks. Much of the impact of climate change is from worsened storms, which do not stick cleanly to national boundaries. The biggest impact of climate change on Florida may well be hurricanes, but simply looking at local temperatures will not detect anything at all — it is the temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean, and off the coast of Africa, which would matter. And indeed, they find (p. 3-4) that local temperature shocks have a very small association with negative impacts, and global temperature shocks have a much larger outcome. These impacts are so large, in fact, that they estimate a social cost of carbon of $1,056, six times higher than the high-end estimates currently in the literature. (p. 5)

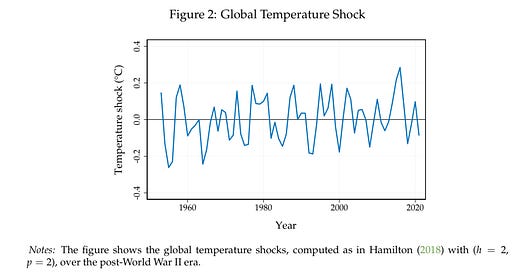

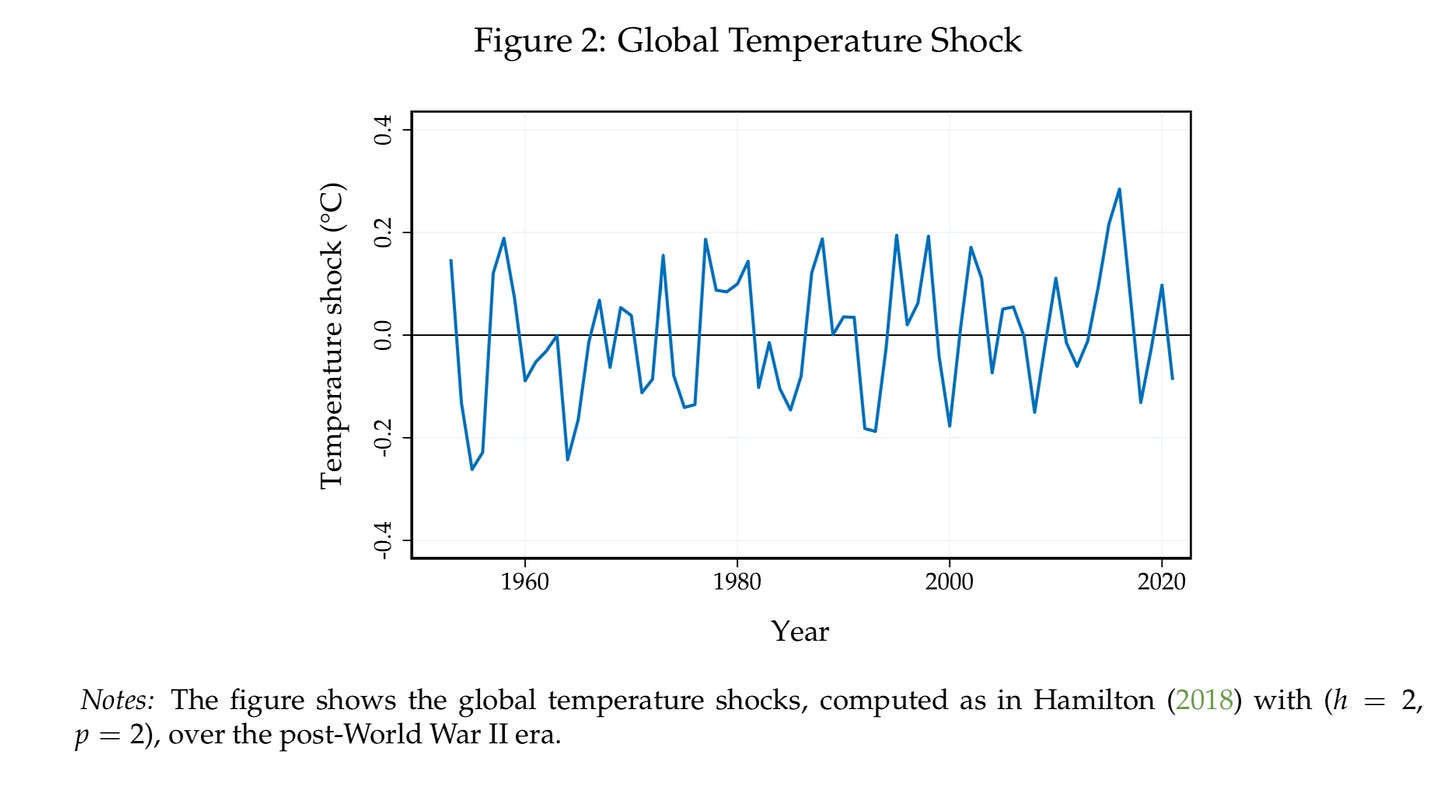

It sounds too big to be true. And frankly, I think that’s the case. They are interested in shocks, as below. Temperatures have been climbing throughout the period, so you need to control for this.

When the globe is unusually warm, you have a shock, which immediately lowers income by a small bit, and then continues lowering income long after the event. This is consistent with disasters being a shock to capital, which then depreciates without replacement, so the story of why most of the effects should be long after is not as implausible as it may seem.

What I am concerned about is taking the figure for losses when the temperature is unusually hot relative to normal, and simply plugging that figure into your DICE model. Where’s the adaptation? Where’s the change in expectations? When Texas suffers an unusual cold snap, it gets a crisis — Minnesota suffering a cold snap is nothing. You cannot take a figure for damages from the equivalent of Texas, and plug it into the equivalent of Minnesota — you will surely get nonsense.

So how should we estimate the harms from climate change? In truth, can we, with any freedom from arbitrarity? Probably not, but we can try to be as reasonably close as we can. Climate change is a very big deal. We should be willing to pay a lot of money to help mitigate it. We should tax carbon. We should fund advance market commitments for economical ways to remove carbon from atmosphere. We should put calcium carbonate in the atmosphere to directly lower temperatures. We should have property owners face the full costs of insuring their property, to encourage mitigation. And we in the developed world do have some outsized moral responsibility to protect our planet.

Nevertheless, the costs of climate change, while high, are not so high as to border on infinite. There is not a chance in the world it’s actually $1,056 per ton, and we should have more respect for humanity’s ability to adapt. How much man can adapt, I do not know; but it is surely more than 0.