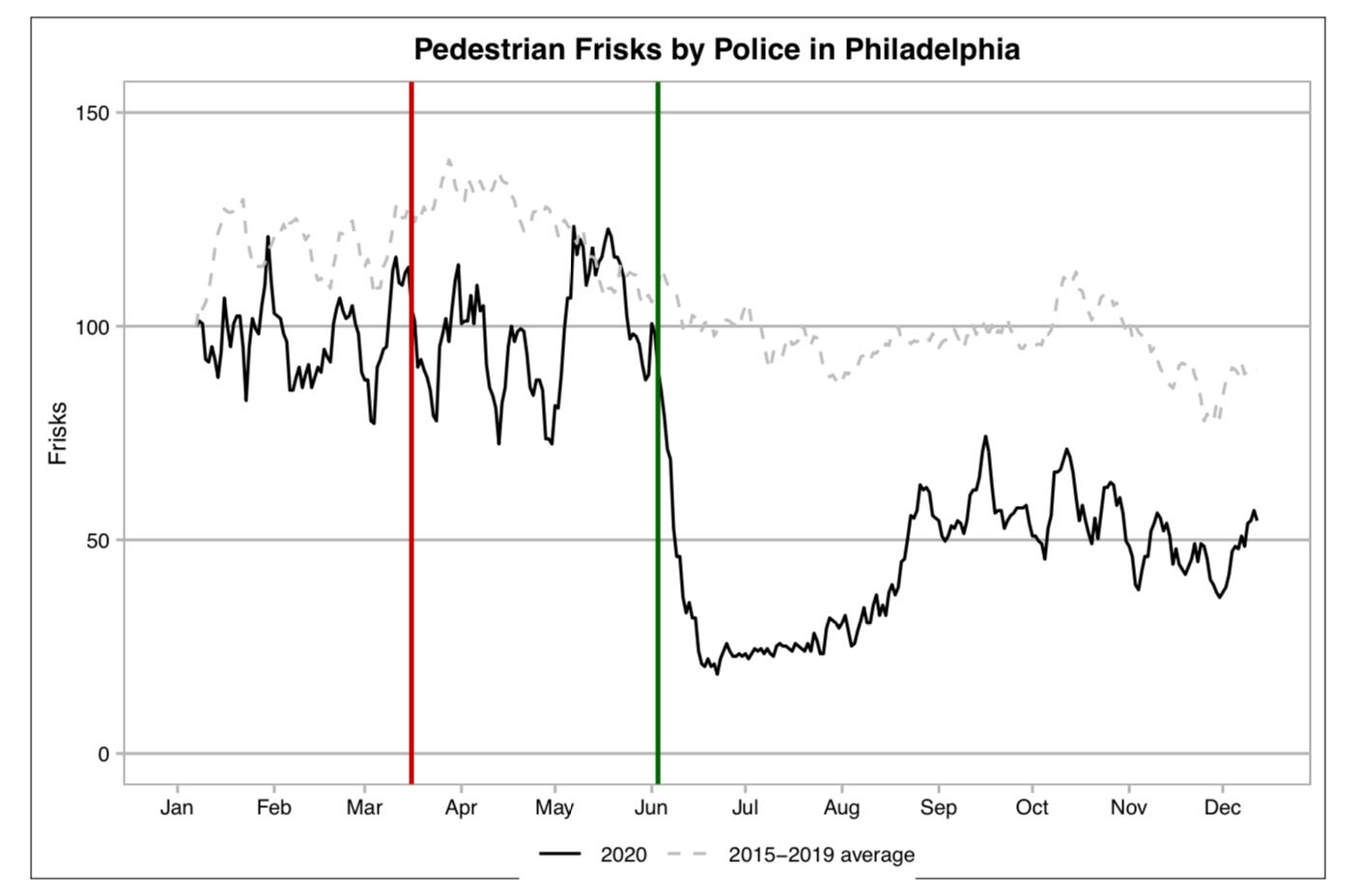

“Depolicing” has happened in America. In the wake of the George Floyd protests, the police now make fewer discretionary stops and are less active in the pursuit of crime. Philadelphia is shown below as an example, but this holds up across many, many cities. Many police departments are understaffed, with retirements and resignations increasing since 2020 faster than replacements can be hired. Crime has increased, with homicides, the most reliable of crimes, increasing 44% between 2019 and 2021. Yet, defunding has not happened. In fact, police spending has increased since the 2020 protests. This change in police behavior has not been due to changes in objective conditions, but due to shifts in attitude and belief. How could this be?

I think the answer lies in a little book called “Managerial Dilemmas” by Gary Miller. The book spends about 200 pages expounding one message: there is no impersonal system of constraints that can bind both the manager and managed. Any system of setting up a firm will leave at least one party with the opportunity to profit by defecting at the expense of others. Someone will set the rules; there will always be ways for them to turn this to their short term advantage. There is no way to specify every contingency in contract ahead of time. This is why a work to rule strike can be crippling – if a union decides to very, very precisely follow all rules at all times, in the most uncharitable manner possible, it would cripple a company.

To illustrate this, let us suppose that there is some industrial concern, which manufactures a product. They could hire people at a fixed salary, and have them work together. However, every person could increase their effective pay by taking it a bit easier – thus leading to a level of work and pay that the employees would not want. So fine, we’ll have managers who assess how much work is being done by each person, and who gain the profit of the industry. This is costly though, and managers can still defect. So alright, we’ll have everyone work individually, and pay them for however much they produce at a fixed rate. There’s a problem though; the workers know better how much time and effort it takes to do a given job. If they produce too much, the company will simply revise the pay scale so you now make the same at a higher level of effort.

And so on, and so on. Unless people disregard their short run interests, any organization will do very poorly relative to what it could be done. The ability to convince people to act in the best way is what Miller defines as “leadership”; this is also why social trust matters. In the past when I heard people talk about social trust, the issues that sprung to mind (like less crime, you don’t have to lock up your bicycle) always struck me as trivial. Social trust goes much deeper than that – it is what allows people to work hard without being a sucker.

The protests of 2020 shifted officer’s beliefs about how they would be treated if they go beyond what is explicitly required by the job. We are now in a low-trust equilibrium, where officers don’t believe they are supported, and so don’t do the things which are essential for fighting crime but cannot be specified ahead of time. Where before they might have worked to their full abilities, they now work only to what is required. It is not necessary that these beliefs be supported by actual fact, either — the belief is sufficient.

So what can we do? While the protests are in some sense “to blame”, I assign them neither moral culpability, nor ask people to radically change their views. One may as well argue with a tsunami. I believe the answer lies in the elected leadership of cities and municipalities taking a rhetorically pro-police line, making it clear that they want more stops, and then rewarding cops who do that. They will have to take the side of the police in incidents which are not egregious. The general public wants the results of policing, but not the process — it is very easy to condemn normal policing. Pay may also need to be increased.

The status quo is not acceptable. Too many people are murdered in America. We know how to stop the murders — stopping people to confiscate weapons — we simply lack the will.

Neat! Coarsely suturing a child's intuitive understanding of incentives (itself cribbed from a book) to some unquestioned reactionary assumptions about the effect of policing and completely incurious discussion of data, then pretending this mixture makes up an argument. Newsflash, homicides are "reliable" because the FBI takes an interest in their statistics not just being made up; that doesn't mean every single homicide is reported in every single region every single year. Just utter drivel, no logical thread whatsoever, truly terminal economist brain.