Teachers often claim to strike for the benefit of the children. Do the things they win benefit their students? Lyon, Kraft, and Steinberg, in “The Causes and Consequences of U.S. Teacher Strikes”, decisively answer this with “no”. Teacher strikes do increase funding, but this funding does not improve student performance. We should update our beliefs away from funding inducing all but the smallest increases in performance, even if this money is spent on improving working conditions, in addition to increasing wages.

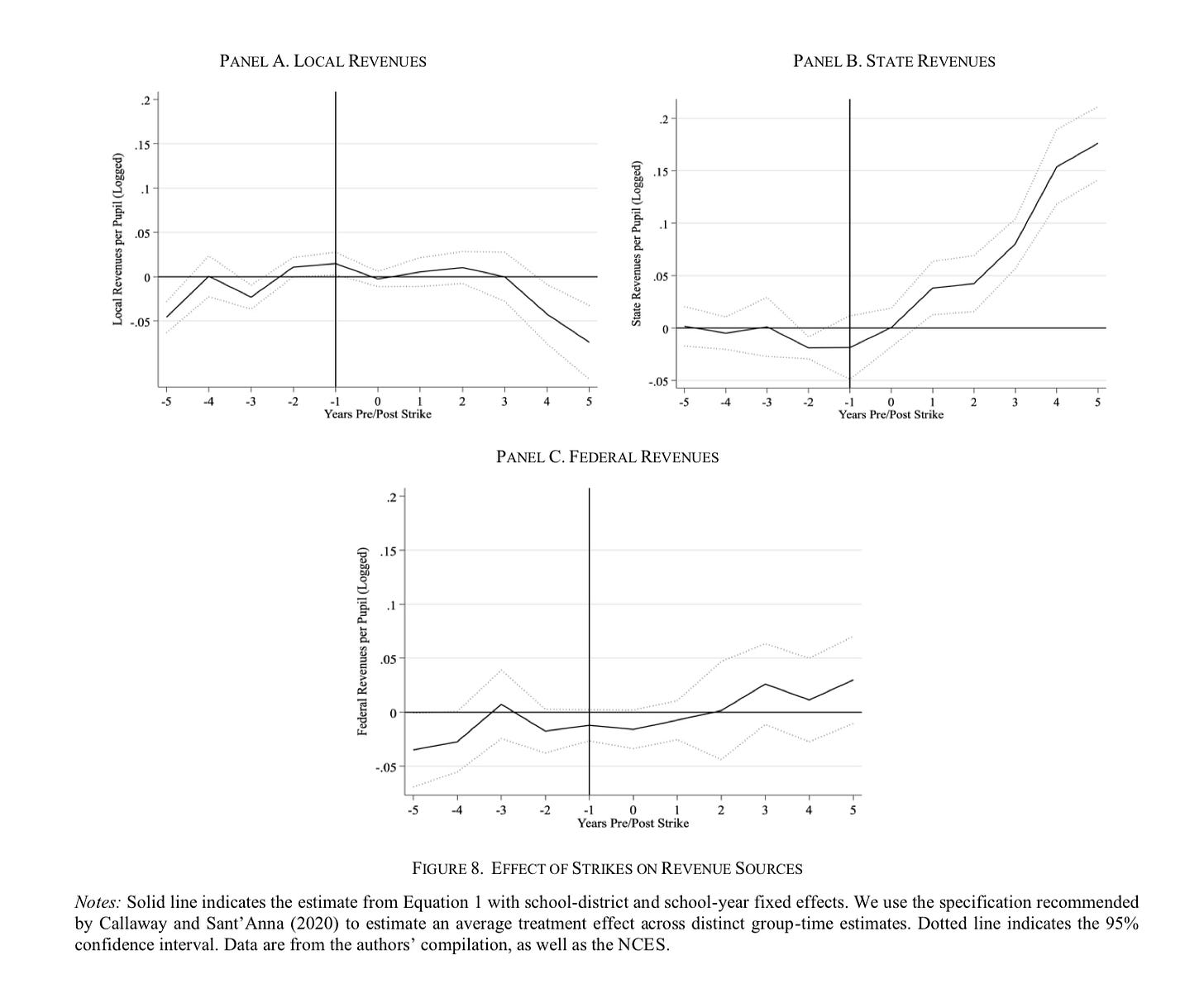

They assemble a dataset on every teacher strike between 2007 and 2023, covering 772 strikes. While some strikes did not result in higher wages, they were by and large successful — compensation rose, after five years, by an average of $10,000. Pupil-teacher ratios fell, and, while more difficult to measure objectively, spending on improving the quality of working conditions rose.

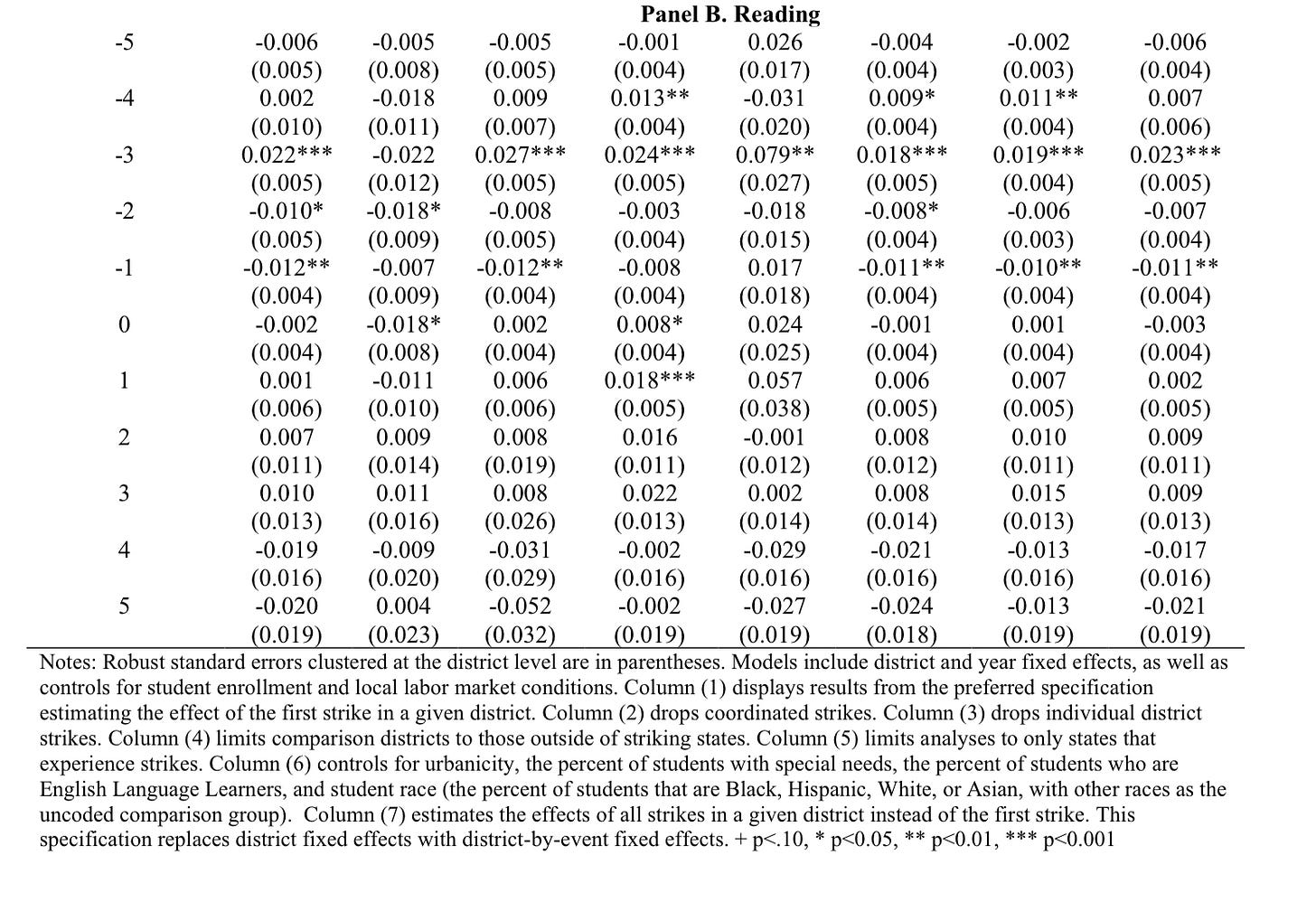

The authors are able to rule out any significant changes in test scores, either positive or negative, to a very high degree of precision. That there is no negative effect is not surprising, if one reads other papers on the effect of strikes on student performance. The median strike is very short, a mere two days. By contrast, other work, such as this paper on Argentinian strikes, considers strikes lasting an average of 88 days. Longer strikes, defined as those lasting more than two weeks, do lead to a small decline in math scores that year, but this decline does not last.

Lyon, Kraft, and Steinberg are using a difference in differences approach to finding the effect. You compare the trend in test scores before the strike, and after the strike. If they substantially diverge, then you can argue that it is in some way due to the strike. Obviously, there are other things going on. It is not the soundest method of determining what caused what. But, it’s a reasonable argument. In section IX they check for robustness against other possible causes. The non-effect is not driven by changes in the composition of students, for example, or spillovers from other districts which also had rises in spending.

Their effect sizes track with what we know from other studies. Jackson and Mackevicius conducted a meta-analysis of every study looking for causal effects of additional funding on school outcomes, and found minuscule effects. An additional thousand dollars per student over four years improved test scores by three hundredths of a standard deviation, and college attendance by a couple of percentage points. These are just fiddlesticks. Another paper — this time from Indonesia — finds that doubling teacher pay made teachers better off, but did not improve outcomes. Strike action is about increasing teacher pay. This may well be justified, but it stands alone. You will not also increase test scores.

P.s.

Amusingly, I have a connection to Matthew Katz, one of the co-authors. A friend of mine lost an election for school board to him. Alas, my friend was seen as too union-friendly! (Though, let us be fair — he absolutely is). It is rather strange to me that Prof. Katz was running there, as Brown is in Providence and the election took place in a Boston suburb. I have heard of people commuting from New Hampshire to Boston, to avoid the taxes and get a cheaper home, but I’ve hardly heard of someone commuting from Boston to Providence!