Should Democrats Moderate on Abortion?

A reply to the critics of Ezra Klein

Recently, Ezra Klein stirred up controversy suggesting that Democrats should be more willing to include people who are pro-life in the political coalition in an appearance on Ross Douthat’s show. Specifically, he said:

“My view is that a lot of people who embrace alarm don’t embrace what I think obviously follows from that alarm, which is the willingness to make strategic and political decisions you find personally discomfiting, even though they are obviously more likely to help you win. Taking political positions that’ll make it more likely to win Senate seats in Kansas and Ohio and Missouri. Trying to open your coalition to people you didn’t want it open to before. Running pro-life Democrats.”

This made a lot of people on twitter mad. In particular, partisans for abortion access pointed out that abortion is something on which the Democratic stance is popular. Referendums on restricting abortion access were defeated by the electorate in Kansas 60:40. Thus, they argue that it is illogical for Democrats to moderate on an issue which is popular.

Other people, more on the right, argued that the issues the Democrats should change on are not abortion rights, which are popular, but on immigration and trans rights, which are (especially the former) not popular. Ezra Klein was, to them, simply pulling his punches to avoid being dogpiled.

All of these perspectives are incorrect. It is not, in general, possible to tell whether changing a policy position would change vote share from a given issue being popular or unpopular. Democrats moderating on abortion is consistent with both increasing and decreasing vote share.

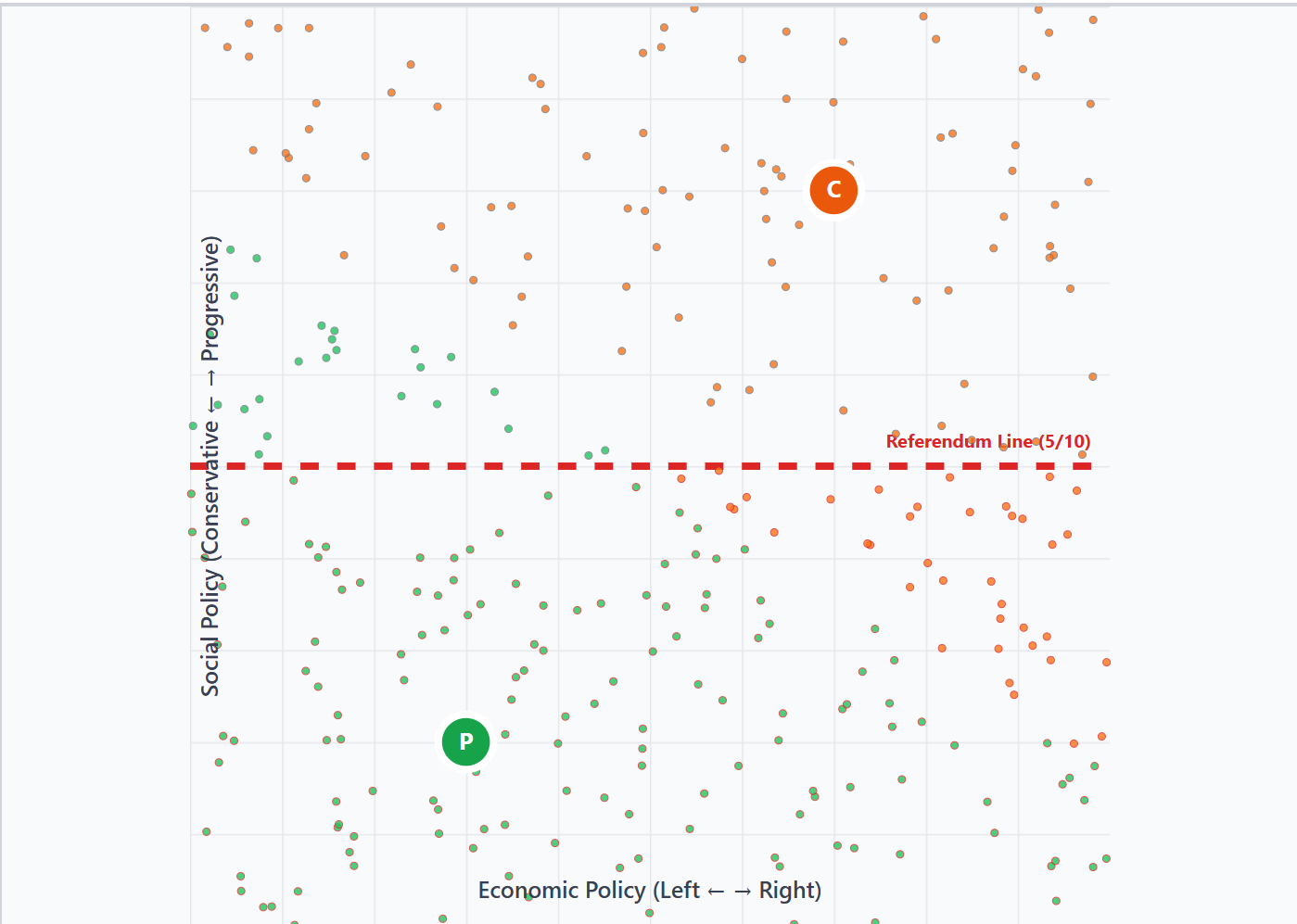

Think about each issue being a dimension. In the example I am building, parties vary in two dimensions, which we’ll label economic and social policy, but the example can be expanded without loss of generality to n dimensions. We will assume that each voter has concave preferences, meaning that they have a point they most prefer, and their utility from other points monotonically declines as we get further away from it. This rules out local maximums. Voters pick whichever candidate is closest to them when they vote. We can say that they face a “transport cost” to vote for someone far away from their ideal point, but we shall set that to zero for now.

The abortion referendum is simply equivalent to a vote on whether abortion access should be above or below some threshold. I constructed this set of data points (using Claude) deliberately that 60% of voters are on the progressive side, and the Democrat is about at the median of the progressive voters. It is trivial to see, though, that they could increase their vote share at any point by moving toward the center. The people at the edges still prefer the Democrats to the Republicans, so you don’t lose them.

Thus we can see how moderating on abortion can raise vote share. It is also possible, under reasonable assumptions, for becoming more extremist on unpopular issues to raise vote share. In this case, we assume that voters, rather than vote for whichever candidate is closest, choose to not vote at all if sufficiently far away. They pay a transport cost, in other words. Now moving away from the edges is costly.

What policies Democrats should choose is hard to say, of course. I am not trying to estimate them here. It is worth noting that if everyone were to vote, Trump would have won by more. It is less likely, then, that an election strategy focusing on turnout would succeed. I want everyone’s take away from this article to be that simply looking at the popularity of an issue is insufficient. You need to consider where the opposition is placed.

Something which bugs me and likely me alone (which is why this comment is at the end) is why we aren’t already at equilibrium. If parties face no transport costs, they should converge to essentially the same positions. We obviously do not, so we must face some transport costs. Either way, it shouldn’t be possible for a party to knowingly choose political positions which would lose. Thoughts on this below.

Fix Trump’s policies as exogenous. Then, the other party has a primary to find a candidate. Voters would like the candidate closest to themselves who will also beat Trump. The decline in utility is a linear function of distance. We shall say that there exists a core of voters who will always prefer Trump to any combination of positions which would beat him. Everybody but them votes in the primary. Candidate entry is unsolvable, so just say that candidates are randomly drawn from the population, and everyone votes. To account for us being uncertain, we’ll say that in each period there is a first order Markov variable, which shifts the mass of voters by some vector.

I have no idea what happens if we repeat this procedure, so that whoever wins the Democratic primary is taken as the fixed point, and we rerun it on the Republican side. Something I would like to know is if this results in parties converging toward the center, or remaining differentiated. Letting me know about any literature on the topic would be much appreciated.

> Something which bugs me and likely me alone (which is why this comment is at the end) is why we aren’t already at equilibrium.

My guess is because politicians don't actually optimize for winning. They want to be liked by their groups and donors, because they are people. If you're going to dinners with and giving talks to pro-choice advocates/evangelical christians/any group, it is mentally difficult to try to appeal to them and be friends with them without starting to genuinely believe in their cause. The people a politician surrounds themself with tends to be the median person of their party, not the median person of the general population.

Someone who actually pushes for the median positions of the population would be able to win. But those people are not common.

I think we generally overestimate how consequentialist people are when they think strategically. Most people believe strongly in a few core principles and values, and they'll stick to those no matter what (and they don't like thinking about the possibility that running candidates with their preferred positions might not work). This applies to candidates and donors too. They've got their pet issues and causes, and they're not willing to accept defeat in the battle to win the war.