The Buses Really SHOULD Be Free

Where the evidence stands on subsidizing public transit

Should the buses be free? I may need to turn in my libertarian card – if I have not already done so, long ago – but the answer is yes, or very close to it. There are reasonable objections, but the case for free buses is much stronger than many people will grant. I would thus support Zohran Mamdani’s plan for free buses in New York City, although with some caveats for that city specifically, and think that many other cities should drop their fares.

In order for subsidizing buses to be optimal, we will need to identify specific market failures. In the case of urban transit, there are three: pollution, congestion, and allocative inefficiency from fixed costs. Buses and trains produce fewer emissions per passenger-mile traveled, which is good; having too many cars on the road makes everyone slower; and public transit (trains in particular) requires high fixed costs to open but low marginal costs thenceforward, thus requiring a ticket price above marginal costs in order to pay back the fixed costs.

These are all good reasons for taxing drivers and subsidizing buses, but we are unsure what the price should be. There is a paper answering this! Almagro, Barbieri, Castillo, Hickok and Salz (2026) is one of the more impressive papers I’ve ever seen, written using detailed data on transiting from Chicago. I think it is worth going in depth through what they are doing, because it is interesting to learn what problem solving looks like in economics today.

Our goal is to answer what the optimal prices and frequencies are for each mode of transit, under different constraints for funding, given the infrastructure we currently have. Incorporating the ability to change the network of roads or trains would make it complicated beyond our ability to answer, so we will not analyze it. We need a few ingredients for this.

We need the relationship between people on the road and travel time, the cost of environmental externalities, and the marginal cost of providing public transit.

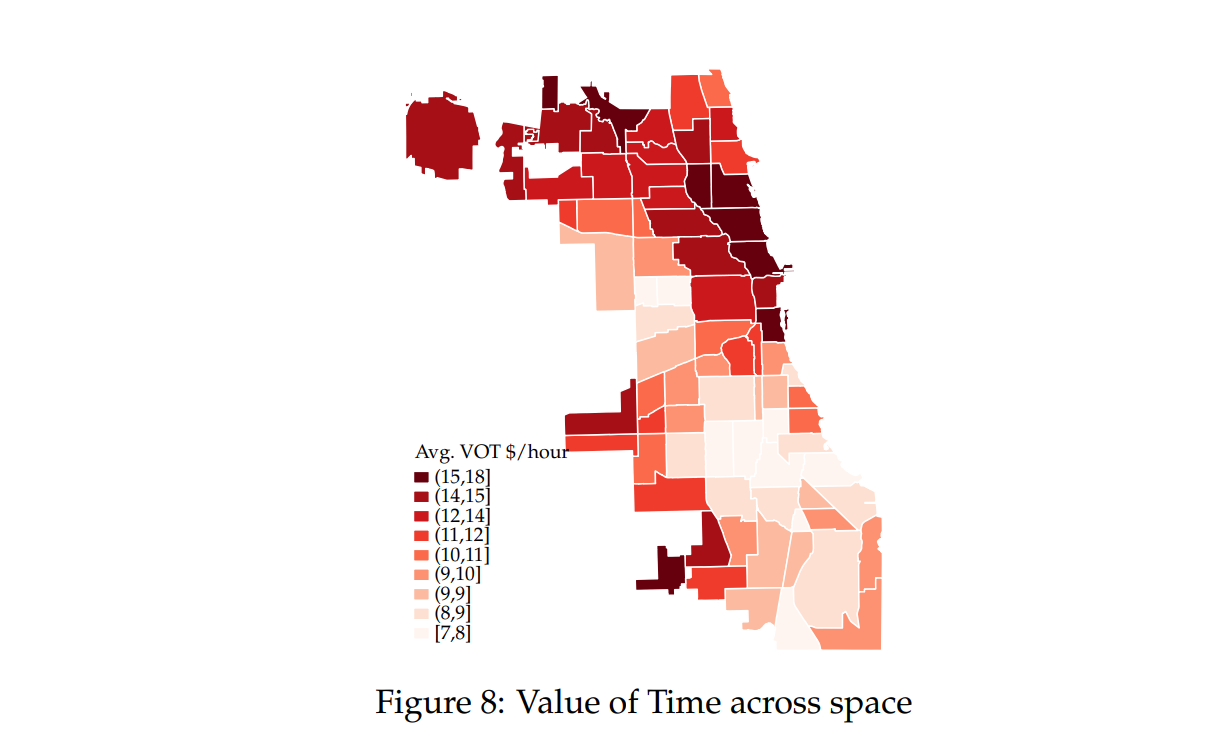

We need to elicit the value which people place upon their time, estimated flexibly so as to account for heterogeneity by income.

We need knowledge of how people substitute from mode to mode as the price changes. In other words, we need to know the demand curves and the cross-price elasticiti

With these, you have enough to simulate the impact of changing anything, including changing frequencies and prices. Of course, getting these parameters is not trivial, but it’s what makes economics exciting to me.

They have the complete data on bus and train trips from the CTA. The bus network (of which there are 127 routes and over 2000 buses) covers the whole city, while the train network goes mainly in and out of the center of the city. They also have data from the city on taxi and ride-hailing apps, as this is entirely recorded and available to the public, although they will drop the taxi. Finally, they infer car trips by using a dataset of mobile phone location data from Veraset, and subtracting out the known bus, train, and ride-hail riders. Since Veraset doesn’t cover everyone, each neighorhood gets multiplied by a factor to match the aggregate data in the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning’s Household Travel Survey.

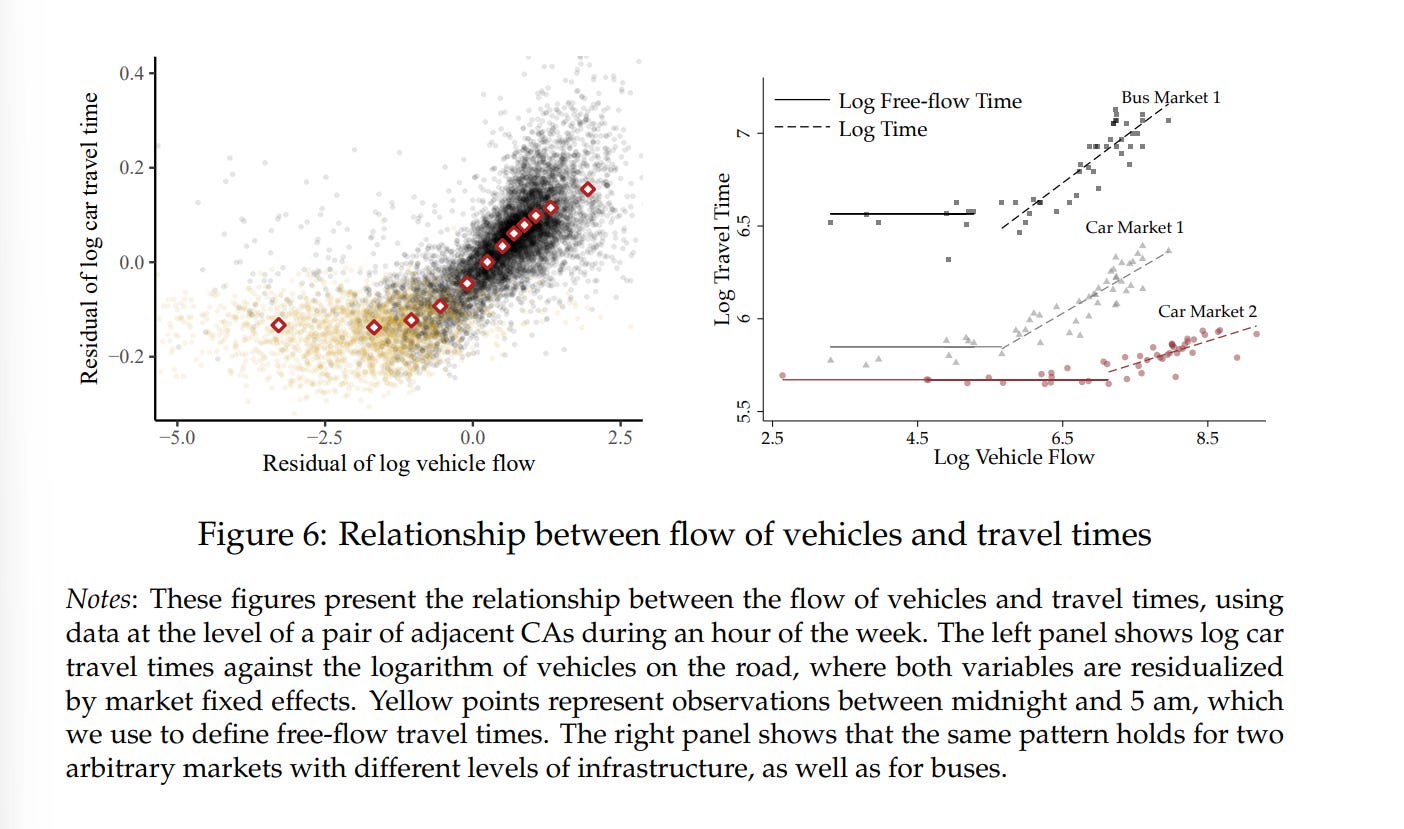

Finding the relationship of traffic density and congestion is easy. You get the travel time between any two points from querying Google Maps, and regressing travel time on density. The hockey stick pattern, where traffic is flat, then increases, leaps off the page, and makes intuitive sense: everyone can travel at full speed until it hits capacity.

Finding the demand curves for each mode is a lot more complicated. There are a bunch of places, nodes, which are connected by edges, each of which has a certain price and free-flow travel speed. The actual travel speed is, of course, jointly determined by the observed relationship between congestion and traffic speed. The utility gained by each consumer is equal to unobserved demand shocks, plus a distribution for preferences over travel time, minus a distribution for preferences over price, plus error. If you are familiar with Berry-Levinsohn-Pakes (1995) (which I have discussed at some length elsewhere) it is an identical set-up, except with travel times taking the place of characteristics.

We need instrumental variables, because otherwise choices might be correlated with unobserved demand shocks. The price might be raised when the sellers of a good anticipate more demand, thus leading you to spuriously associate higher prices with a higher quantity consumed. For public transit and cars, the price is fixed long in advance, so we can argue reasonably that it’s exogenous. For ride-hailing apps, they use the change in price for weekday trips that go in or out of The Loop between 6 am and 10pm, comparing demand just before and just after.

For travel times, the concern is that a positive demand shock leads to more people using the roads, making trips slower. Again, you would spuriously believe that slower trips make more people use them. The instrumental variable they use is the free-flow travel times, which are affected by permanent infrastructure like a highway.

The results pass basic sanity checks. The implied value of time is substantially higher on the richer North Side, and goes down in the South Side, with Hyde Park (home of UChicago) being the exception. People going to and from the airports place a high value on their time. Looking at what people substitute to and from, people without cars are much more likely to substitute to making no trip at all.

The social planner’s problem is to set the prices for which consumer welfare is maximized, and they find that simulating it over and over until it converges on an optimum. They do this three times, analyzing when the planner has control of transit alone, when the planner has transit alone and must balance the budget, and when the planner can simultaneously choose both the price and frequency of transit and the price of driving a car.

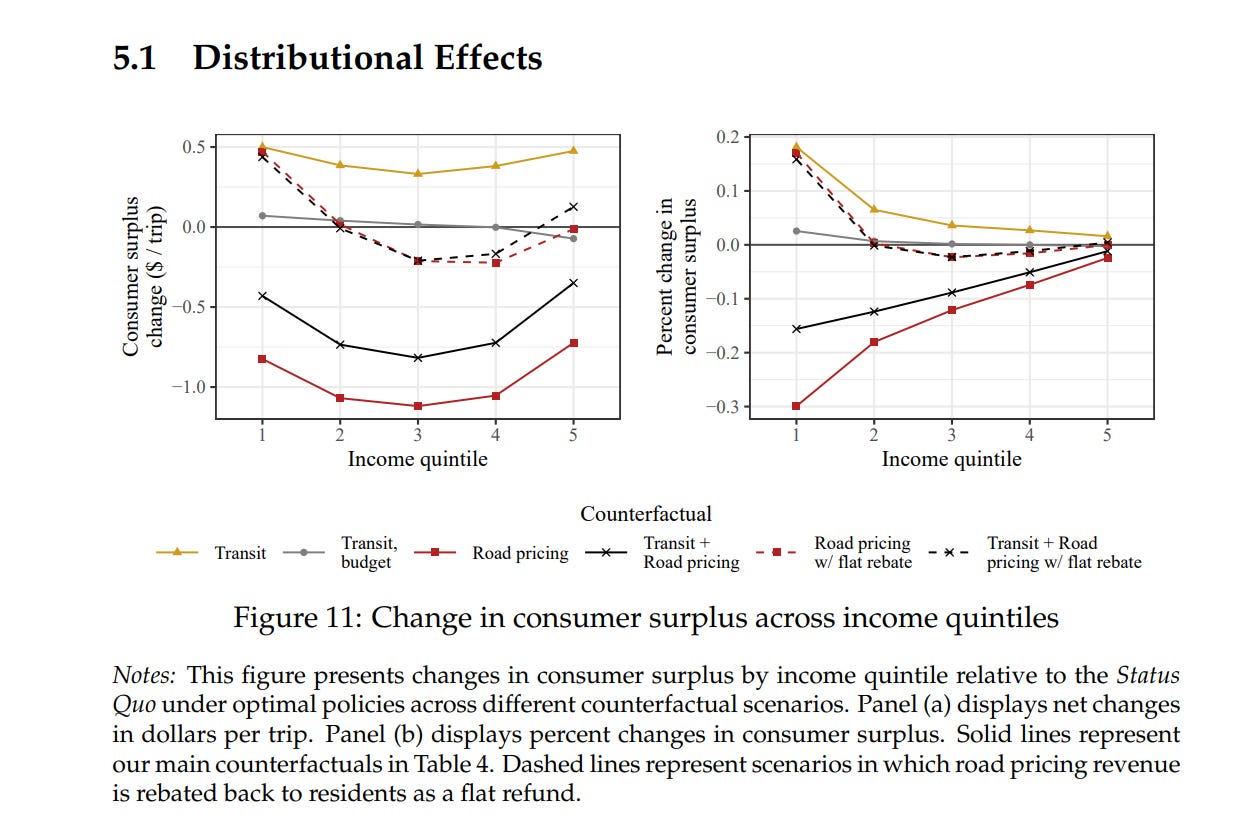

In all cases, the optimal prices of buses and trains go down. If the planner only has control of transit pricing, but does not face a budget constraint, the optimal price to get on a bus is negative. If the planner of public transit is forced to be self-sufficient, then prices are positive, but still a third of what they once were. If one can combine road pricing and transit control, even with the need to cross-subsidize, the price of buses and trains is much smaller than the status quo. The welfare gains can only happen when the taxes are rebated to the consumer; if they are simply taken and not spent, it will lower welfare.

The results for price are extremely robust. Arbitrarily changing any of the parameters by 10% shifts the optimal price by less than two cents. Frequency is less robust, but still can tolerate substantial errors in the parameters. The benefits accrue mainly to those at the bottom (who use public transit a lot) and those at the top (who have a very high value of time, and in the case of trains, use them a lot).

Some comments. The gains from road pricing come from people substituting from roads onto other modes of transit. They do not come from people changing the time that they leave. While the exact time that people leave varies from day-to-day, that does not mean that it is flexible. Gabriel Kreindler (2023) covers an experiment in Bangalore, India, where there is no public transit network to speak of, and finds that optimally pricing the roads leads to much smaller welfare gains that you would get if everyone had homogeneous preferences. I am, for that reason, not very impressed by time-varying tolls if there is not something to substitute to, unless the purpose is raising revenue.

I am thus less confident in the utility of road pricing – or certainly, how easy selling it is to the public. The benefits of road pricing come mainly from environmental externalities, not through reducing congestion. This means that your results change sharply with your estimate of the social cost of carbon, and you cannot pitch it as “we get rid of traffic and make us all better off”.

The argument for buses being free, rather than a small price, is basically just to simplify loading and unloading. The hope is that people just hop on and off, without fussing about paying and holding up the bus. This is outside of the model, but commonsense also indicates that there should be discontinuous demand at 0 dollars versus any positive sum. (Some people, like me, strongly dislike spending anything at all, and will behave quite differently when there is a small fee).

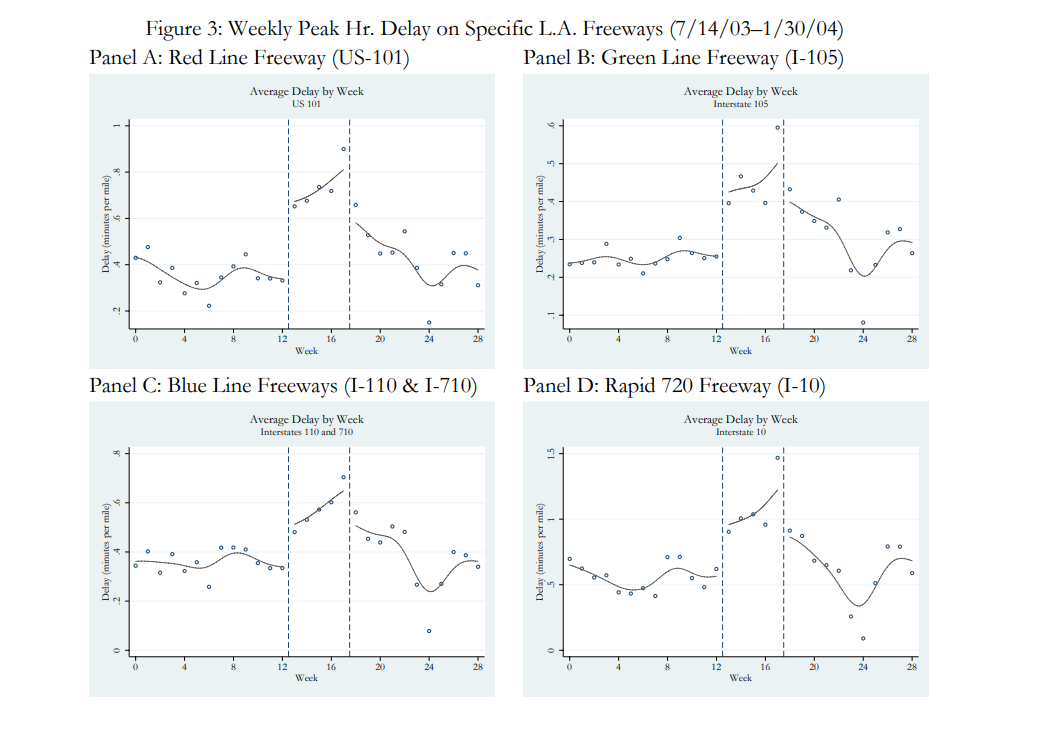

Their results accord with other literature. Parry and Small (2009) estimate optimal subsidies to fares with a long formula essentially toting up the net costs and benefits, and find that basically every transit system they study should have higher subsidies to riders. We should not take the fact that transit riders might be only a small portion of the total commuters to mean that their effects are trivial. A great example of this can be found in Michael Anderson’s 2014 paper on the shutdown due to strike of the Los Angeles metro system. In 2003, the MTA union went on strike, shutting down the train system. Despite being a very small system, congestion sharply increased both in general, and even more so along the highways which the train ran down. You dream of a regression discontinuity this clean.

The other commonality in the literature is that the Almagro-Barbieri-Castillo-Hickok-Salz approach actually understates the welfare effects, because it totally abstracts away from people endogenously changing where they live. Barwick, Li, Waxman, Wu, and Xia (2021) allow for people to reallocate themselves spatially around Beijing, and estimate that congestion pricing, when rebated, would raise welfare, that the actual subway expansion produced comparable gains, and combining the observed subway expansion with the hypothetical congestion pricing would produce the largest welfare gains. Nick Tsvianidis (2026) studies the impact of bus rapid transit in Bogota, and finds that the welfare gains were twice what would have been estimated without including people reallocating themselves in space.

What objections are there? Received wisdom on twitter these days is that you need fares in order to screen out undesirable elements who will make the experience unpleasant for others. Fares, then, are a screening device. This is not in the model. It would show up as an unobserved correlation between price and demand shocks.

However, I think this is more relevant for trains, rather than buses. Buses are already free for the homeless, in practice. You just get on. Kicking someone off of the bus is an enormous hassle, so the drivers just let it go. Trains are gated in order to collect fares already, so filtering out actually works. We could get the best of both worlds if we required the use of a bank-card to scan in, as most serious transit systems do, and then rebate a large portion of the fare at a later date. This may fail for equity reasons, because it is explicitly hostile to people who are not in the banking system. In any case, it suggests that train prices are biased down, while bus prices are unaffected.

The model also excludes the possibility of investment into fixed capital, like a new train line, funded by fares. If fares can be spent on fixed expenses but not general funds, then there is a case for higher fares than what they calculate. However, I do not think this is (in practice) the only way that funds for capital expenditures can be raised, and it is only really relevant to train lines. New bus routes do not require the same exorbitant expense.

I think the best argument against free buses is that productivity might be endogenous to needing to fund itself. If the transit agency is insulated from needing to pay its own way, then it doesn’t need to try too hard to minimize costs. The agency might spend too much on technically-legal but morally-condemnable graft and corruption – paying the union too much, or not being picky in procurement – or they may be unwilling to innovate or introduce new products.

Still, I think free buses are defensible against both of these charges. The problems with government-owned businesses become much stronger when the output is not clearly defined. The Soviet state-owned enterprises were notorious for trading every possible attribute of quality to just pump out more units to meet the quota. Here, however, I think we have a measure of quality which actually basically encompasses what people care about – frequency. Further, even if a company were to run it, there really isn’t much out there to innovate on in the world of bus routes. The tools that a private company would use to optimize routing can be used by a government-owned company too – demand estimation still works even when there are subsidies. Once we start subsidizing them at all – as we should, because we want more people to ride them – we are bound to diminish the incentives for cost-control. It is a matter of political will, and little more.

I do have some caveats for New York City in particular. The gain in welfare is from pulling people off of the roads, and less so from people changing walking to the bus (and still less for people changing from the subway to the bus). It would not be unreasonable to keep the fares on buses in Manhattan, while dropping them in the other boroughs.

This was not the view that I held going into learning about this. However, the weight of the evidence is clear: the positive externalities from more people using public transit are quite strong, and we would be better off with many more people using it.

You mention the issue of free buses leading to enshitification but don’t really reckon with the degree to which that enahitification reduces the utility of buses for riders. If a bus and car are equally convenient but I run a real risk of getting screamed at by an insane junkie on a bus I’m going to drive. So if you want buses to be free and actually useful you need to price in the cost of keeping them safe and pleasant.

I like the idea of free fares in both theory and practice -- we have free buses in my hometown, and it's great -- but my main concern is that in New York City and in other places it's not clear that it's the best marginal use of transit money and political capital. There's a finite pool of money that people are willing to spend on transit, generally, and so going fare-free trades off against service improvements.

I'm a bit puzzled by the safety argument against free fares, although this is admittedly because I generally feel pretty safe on public transit no matter what. But to the extent that I think about safety on public transit, it's that more riders -> more safety. I'm kind of skeptical that some of those riders being homeless/etc. could change it, unless it's 100% having effects on the homeless? And we also probably want the homeless people to have reliable transit to help them get out of homelessness! So you might be being a bit too generous to it.