Introduction:

The first night game was played in 1935 by the Cincinnati Reds; its popularity exploded after the end of wartime rationing. By 1950, Edwin O’Connor wrote in the Atlantic that “95 per cent of all teams in organized baseball play night baseball almost exclusively. Of the 1232 games to be played in the major leagues this year, more than a third will be played after dark; during the months of May, June, July, and August, such teams as the St. Louis Cardinals, the Washington Senators, the Boston Braves, and the St. Louis Browns have voluntarily scheduled not a single daytime game.” (O’Connor, 1950). Due to at first refusing to adopt the technology, and then being barred due to neighborhood bylaws, the Chicago Cubs were alone in totally refusing to play night games – they did not play their first until 1988, decades after everyone else. Even today, the Cubs are limited to 35 night games a year (out of 81 home games), which is substantially less than the average number of night games (which is 54) (Yellon, 2021).

The Chicago Cubs were also very bad for a very long time. From 1908 to 2016, they did not win the World Series. In fact, they did not even win the pennant from 1945 on. They became known for choking down the stretch, such as in the great collapse of 1969, when the Cubs went 8 and 17 in the month of September to lose an 8 game lead to the New York Mets. Between 1969 and 1980, the Cubs had a .516 win percentage before the All-Star break, and a .450 win percentage afterwards. (Bernstein, 2008)

Many people thought the two were connected — the Cubs, having to play out in the hot summer Chicago weather, were simply worn down by the end of the season. General manager Dallas Green is quite explicit in his 1985 letter to fans about this; one of the reasons why lights are needed is to “avoid the heat and dog days of summer which, even though we won last year, puts our players at a disadvantage.” (Green, 1985). However, there has not been, to this point, an empirical exploration of whether this is actually true.

I test whether such a connection exists. If playing day games when others played night games caused late season collapses, then the winning percentage (relative to the other months in the season) should be higher in the opening months and lower in the closing months. What is more, I can argue that this relationship is causal – comparing within the year controls for unobservables, and there is no other plausible argument why they specifically would be worse relative to other teams towards the end of the year rather than the beginning.

I compiled the games won and lost for each month of every season, from 2023 to 1906. I dropped the Covid season, 2020, and the two strike shortened seasons of 1994 and 1981 before I looked at the data, both because they were substantially different in nature in the other seasons, and to forestall the possibility of p-hacking. What we should expect to see, if there was a real effect, is that the win percentages by month will not be significantly different from the other months before night games, will be significantly different (such that it is higher in the beginning of the season, and lower towards the end), and either return to no significant difference or have an attenuated version of the effect (as the Cubs still play fewer night games). I will also look at the win/loss record in multi month blocks, such as spring vs the end of the season. Indeed, breaking the data down into March+April+May, vs August+September+October, provides the clearest demonstration of the effect we’re looking for.

Results

The most important result is in table 1. The monthly win percentage went down at the end of the season compared to the beginning, but only in the period where the rest of the league was playing night games. This explains a small part of the variance (note the low R-squared) but is strongly significant.

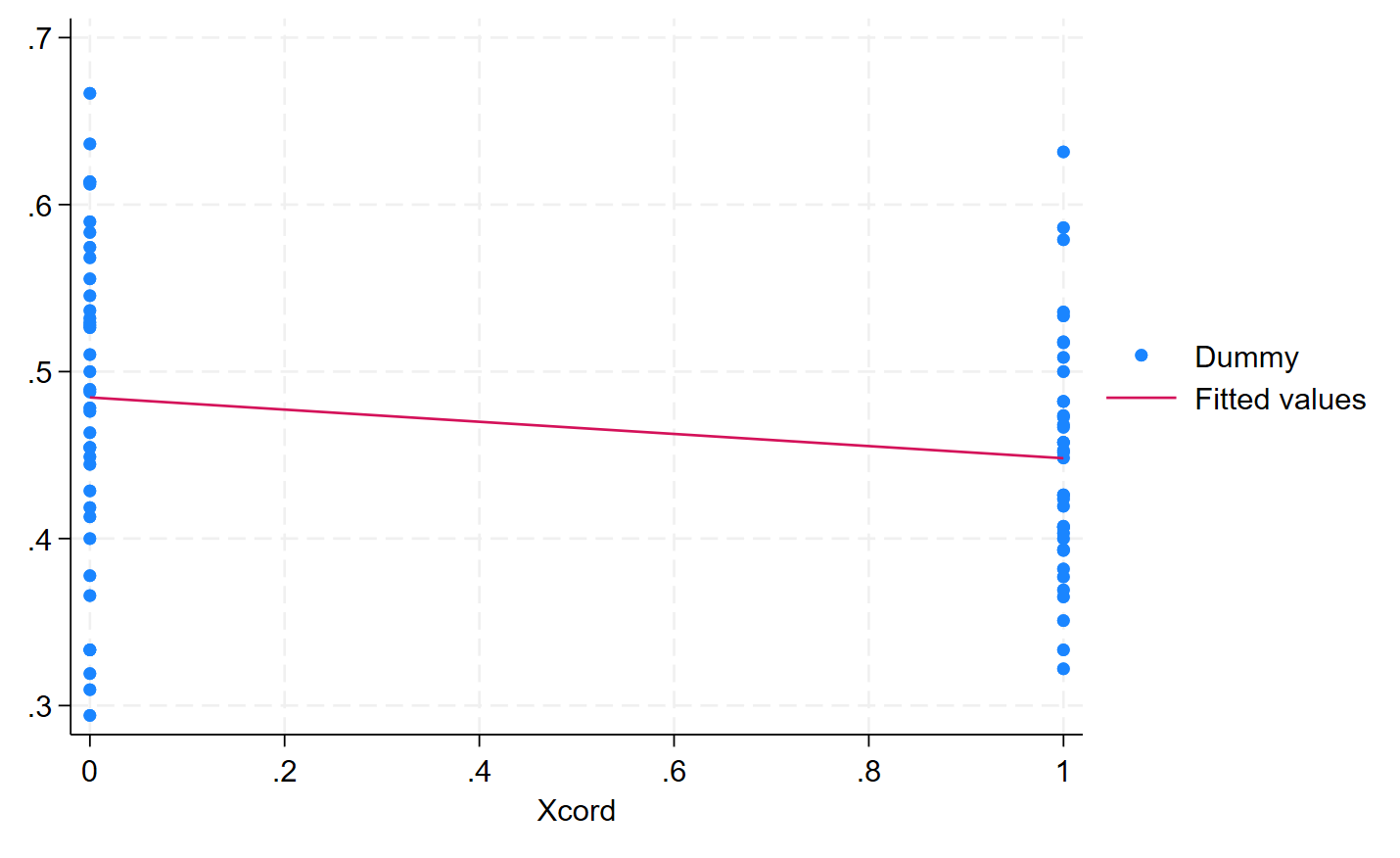

Represented graphically, it is this:

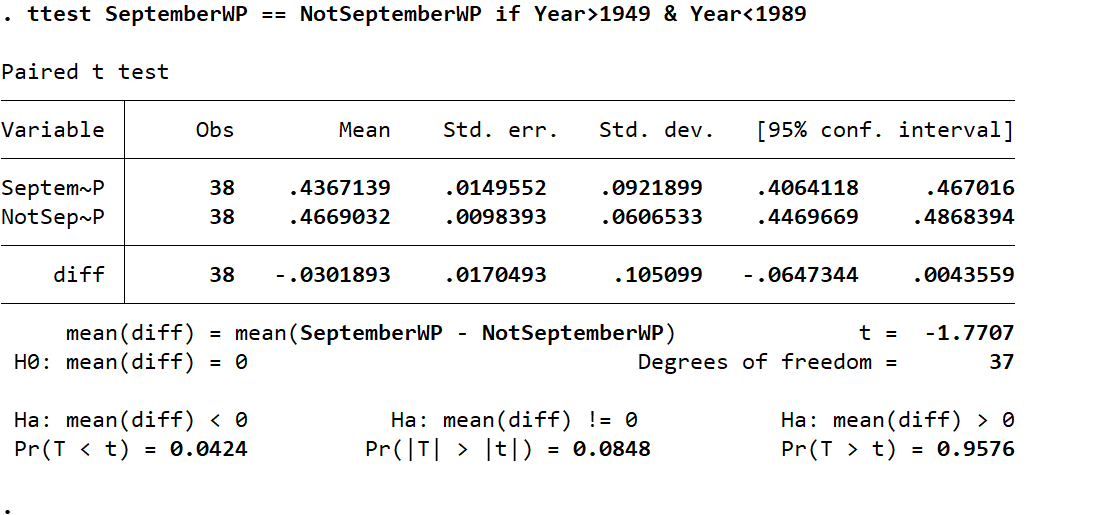

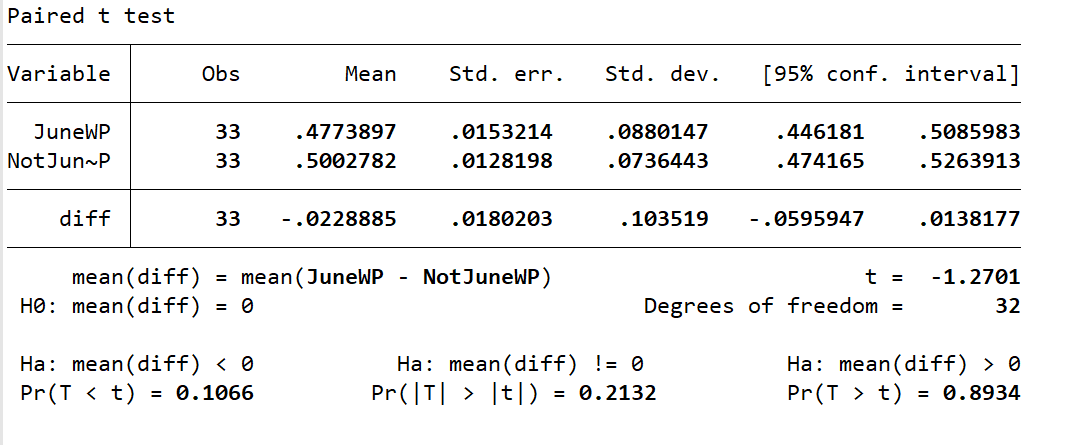

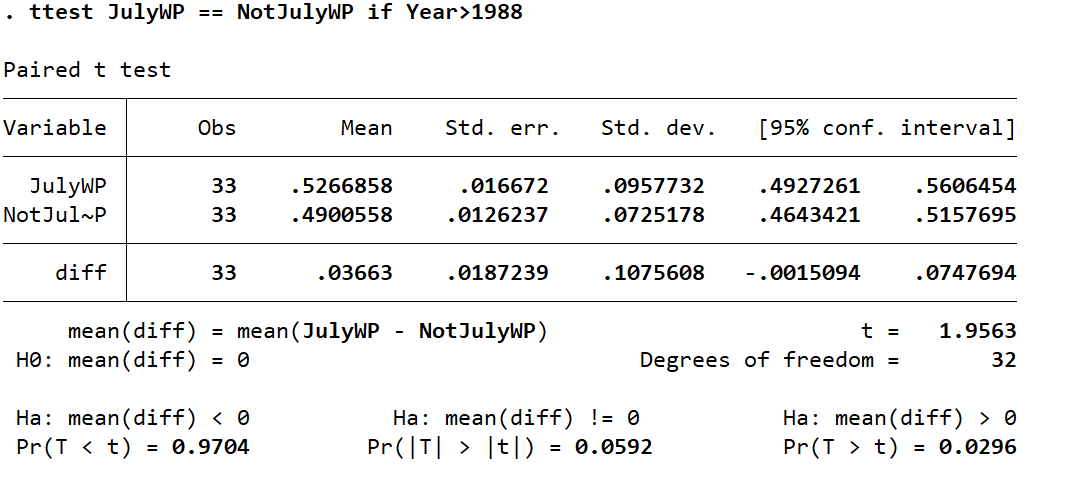

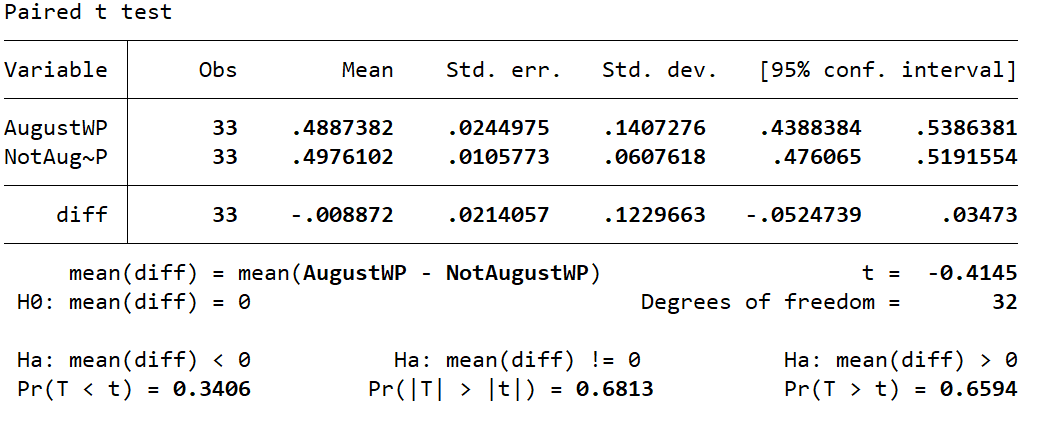

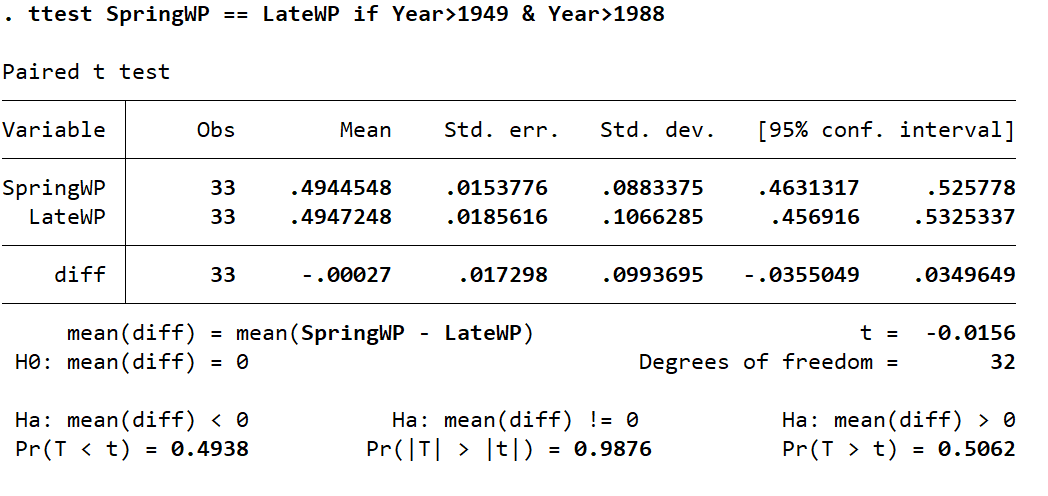

You’ll note that the result is not significant at a 95% confidence interval if we are using a two-sided test, but is if we are using a one-sided test, as our hypothesis would predict. (Table 2) Running the same test on the period before widespread night games, and the period after the Cubs adopted night games themselves, gives us a null. (Table 21 and Table 23) These are done as t-tests, rather than linear regressions, for convenience.

“Obs” is the number of seasons in the sample (1981 was dropped), and “mean” is the average win percentage during that time of year. In the spring they won 48% of games — in the later parts of the season, they won 44%. The “Pr(T>t)” is giving the odds out of 1 that that difference would occur by chance, if the two values were in fact the same. Given that it would only happen every 1 in 40 times by chance, we can reject the idea that they performed worse purely by chance.

Breaking down by month reveals that this is driven by an overperformance in May, and underperformance in September. (Tables 10 and Table 14). Meanwhile, tests month by month show an underperformance in May, in the period before the adoption of night lights (Table 4), and an overperformance in July after universal nightlights (Table 18), if we use a one sided hypothesis test in both instances. A two sided hypothesis test would not reveal a significant difference, however. (We are using one sided hypothesis tests in the prior case because we have a theoretical reason to favor one side or the other, determined long before we looked at the data). The complete t-tests by month can be found in the tables section, where all of the months or specifications not mentioned gave null results.

Conclusions:

The Cubs really were harmed by their late adoption of night lights. The effect is small, but statistically significant. While the primary reason the Cubs were unsuccessful lay in the cheapness of the Wrigley family and the Tribune Company and the notoriously poor farm system, the wearying effects of playing in the summer heat contributed to their late season collapses. If they were harmed before, then they are likely harmed now by the limits on the number of night games played, and should consider playing the full complement of night games. However, given the small effect size, it may be worthwhile to retain the now iconic Wrigley day games, which are often well-attended. Certainly this could give some statistical heft to any arguments by present Cubs ownership that the relative dearth of night games is to their detriment.

References:

Bernstein, P. (2008, August 5). Night and Day: What’s the Baseball Difference? https://www.espn.com/espnmag/story?id=3520021

Green, D. (1985, July 19). [Letter to Cubs Season Ticket Holders] https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22941860/dallasgreen1985letter.pdf

O’Connor, E. (1950, August). What Night Does to Baseball. The Atlantic

Yellon, A. (2021, October 21) It’s time for the city of Chicago to repeal the Wrigley Field night game ordinance, https://www.bleedcubbieblue.com/2021/10/21/22736286/wrigley-field-night-game-ordinance-city-of-chicago-repeal-do-it-now

Tables:

Really cool article! I find your empirical design super compelling and love how you motivate the question and introduce the data and results.

I wonder what Graph 1 would look like using a box plot. It would also be interesting to test whether other teams experienced the same slump with win/loss data for all teams. You could regress win percentage (Y) on the share of night games (X), a dummy indicator for late-season months (Z), and an interaction between the share of night games and the dummy for late-season months:

Y = a + b*X + c*Z + d*X*Z + e ----> reg Y X i.Z X##i.Z

The coefficient d would capture the marginal association between night games and win percentages in late-season months. An even simpler design would be a regression of the difference in win percentages between late- and early-season months on the share of night games.

Lastly, I wonder how omitted variables might threaten your causal interpretation. Is it possible that baseball teams in cold-weather climates are both less likely to have night games (because they do not need to avoid scorching daytime temperatures) and more likely to experience late-season slumps (because colder weather impacts performance as well)?

Again, great article and I look forward to seeing what else you publish!