The End of Competition in America?

Common ownership and the implications for antitrust

In the last 40 years, we have seen an extraordinary trend toward common ownership. Index funds, which do nothing but hold a diversified portfolio of major stocks, control 16% of the U.S. stock market, with many other funds implicitly following the index. Large institutional investors like Goldman Sachs or state pension funds control yet more of the stock market.

With common ownership comes the possibility of anti-competitive behavior. The concern is that, by owning parts of many companies, they may place a weight on other companies’ profits. Rather than compete with each other, they would collusively increase prices, position products further away from each other, fail to minimize costs, and contract in inefficient ways.

I would like to approach this essay like a criminal prosecution. First a motive, then the weapon, then the crime. Specifically, we first need to show that there is a motive to behave in anti-competitive ways. Then, we need to show that the incentives faced by firms have passed through to the incentives faced by managers. Finally, we need to see if this has turned into action. Have markups increased? Have firms changed their behavior to not compete with each other, such as by changing the characteristics of their products to be more dissimilar to each other? Finally, we will discuss whether common ownership would increase innovation, by allowing firms to internalize the fixed costs of research and development.

I argue that the motive is there. If index funds were awakened to it, they would be able to make the world considerably worse while increasing their profits. I also believe that stock holdings are sufficiently heterogenous that institutional investors waking up would not lead to them producing the efficient amount, which would be the case in a representative agent framework. Second, the evidence for it passing through to managerial incentives is there, but weak. To the extent that it is happening, it is through giving managers fewer incentives to make profits at all. Finally, the very best evidence shows no effects on markups. However, markups are not the only channel through which welfare might be affected, and there is evidence that it has reduced product competition. Finally, the evidence for institutional ownership increasing innovation is very poor, with one of the primary studies suffering from serious data errors that necessitate throwing it out entirely. Back of the envelope considerations suggest that this could entirely flip around the welfare losses, but more work is needed.

First, the motive. Institutional investors could greatly increase their profits through anti-competitive behavior. We’re not entirely sure how much, but simple estimates pencil out in the trillions of dollars. This is potentially a really big deal. All investors need to do is place a weight upon other firms’ profits, not just each firm caring only about itself.

I am going to detour briefly on how we deal with common ownership mathematically. The weight you place on profits is denominated by k, which is between 0 and 1. You list all of the firms on the sides of a square matrix. A firm owns itself, so its weight on its own profits is always 1. If they have no shared owners, the firm will place a weight of 0 on other firms. As they share more and more investors, the weight changes to some intermediate value. Note that these values do not have to be symmetric – an investor might control all of one firm and part of another. You can express this as a Modified Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (MHHI), which is just a simple modification of the standard measure of firm concentration.

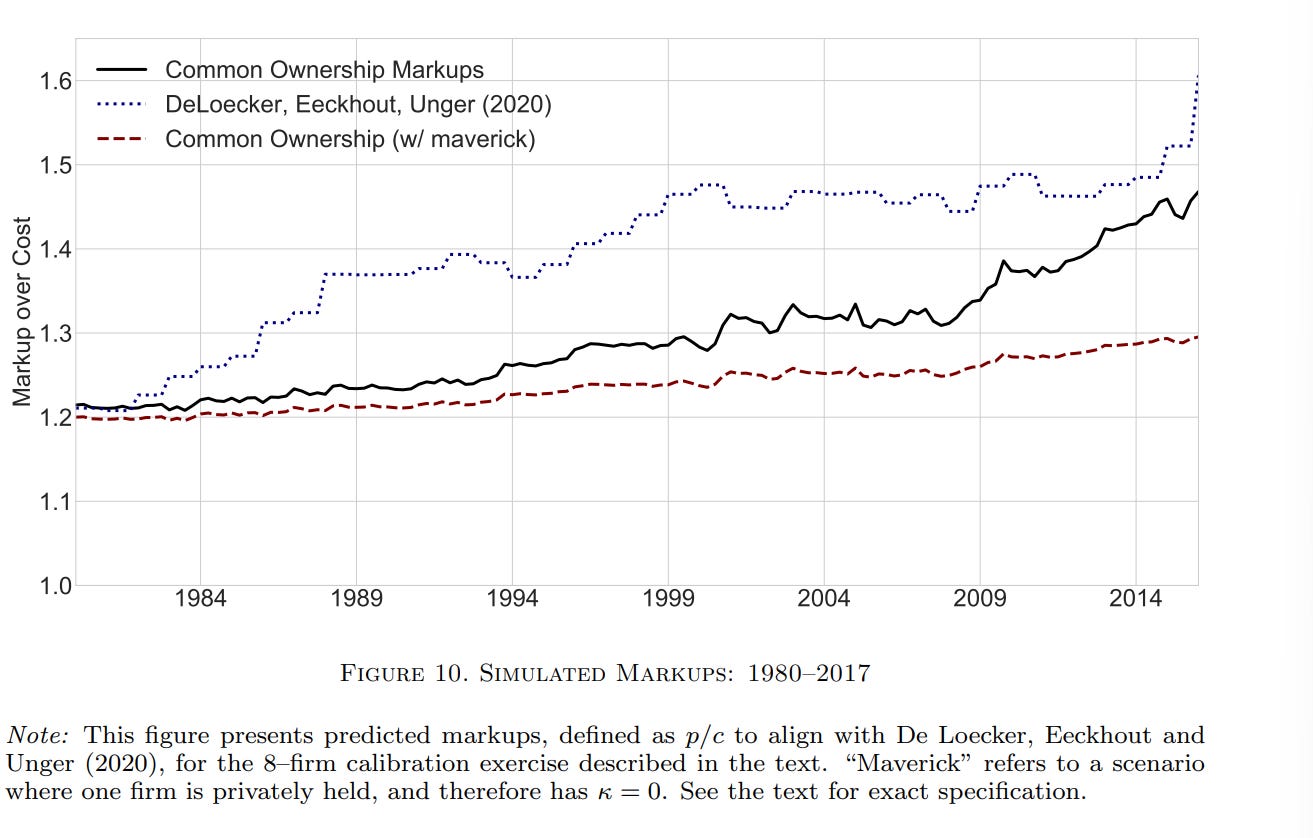

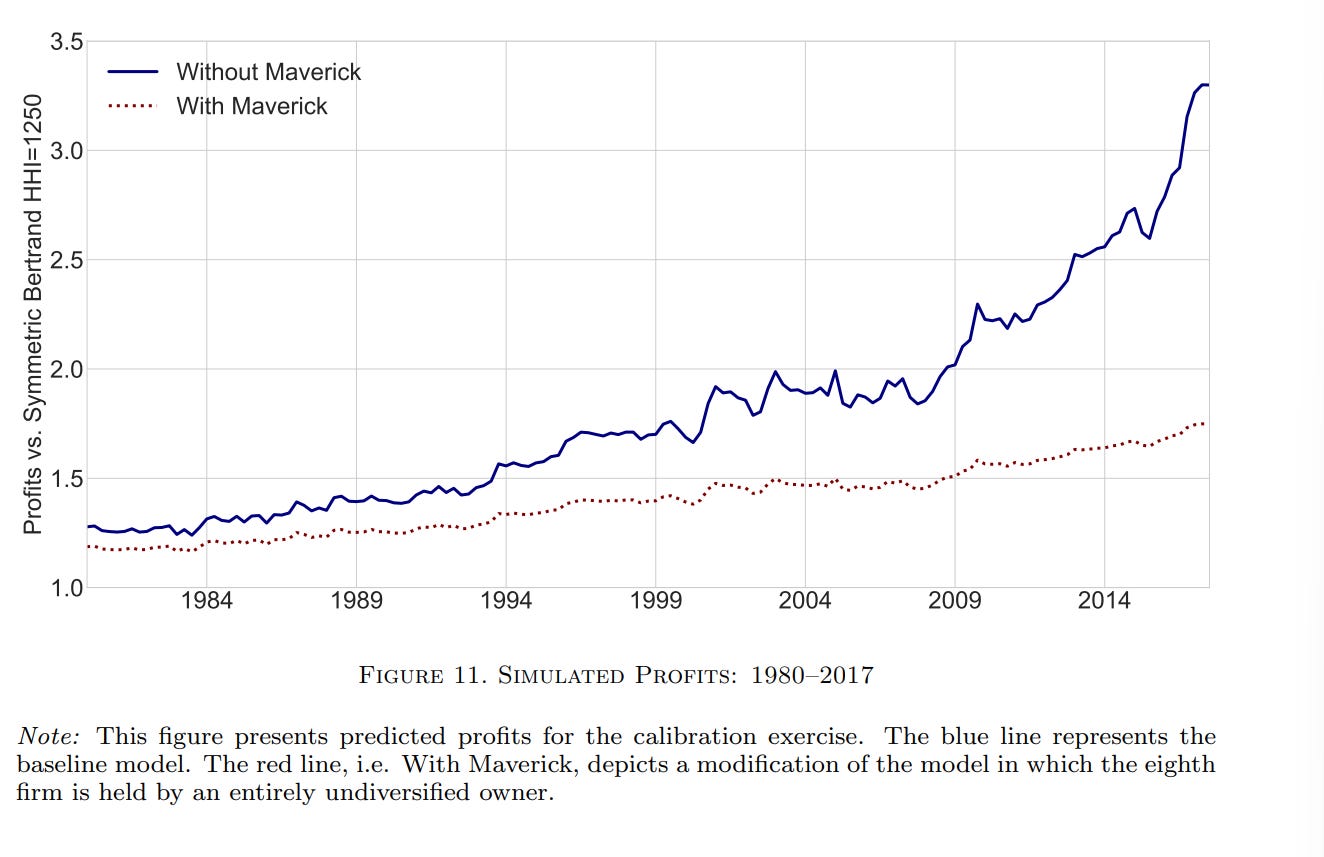

Backus, Conlon, and Sinkinson (2021) simulate what would happen if institutional investors were to fully take into account the profit weights which would be implied by their actual ownership. Doing this exactingly would require incredible amounts of information on all industries – it’s work enough doing it for one – so they have a quite simplified model of the economy. All firms are symmetrical, and face logit demand (so substitution between industries is given entirely by market shares – the development of mixed-logit models like BLP was to deal with this, by the way). They start by calibrating parameters to match De Loecker, Eeckhout and Unger (202) for the average markup and Eaton and Kortum (2002) for the own-price elasticity, and then change the profit weights k. They generate an increase in markups which is much larger than the already likely too high markups of DLEU (2020).

Profits would greatly increase as well, almost tripling.

Edererer and Pellegrino (2023) is a more worked out take on the possible gains from investors behaving optimally for themselves. In particular, they allow for the product characteristics to change, and thus have a very general demand system. (People have preferences over characteristics, and increasingly disprefer products as they get further from their ideal). They also find that common ownership would cause a loss of consumer surplus on the order of trillions of dollars.

All investors are consumers as well. If index fund holdings were spread evenly across the population, then there would actually be no monopoly pricing at all. They would collude to produce the first-best optimum level of output, rather than try and increase their profits at all. (A similar argument is made in the case of environmental externalities by Kwok, Spiro, and Van Benthem (2025).) It seems fairly obvious that, with wealth inequality as large as it is, that the optimal common ownership behavior involves pricing monopolistically. I simply note that accounting for consumption will make the picture much more complicated, and tend to reduce the degree of distortions.

Next, the smoking gun. Managers cannot be expected to know the complete stockholdings of their shareholders. No one is seriously alleging that common ownership would be affecting prices through the channel of Vanguard calling up the CEO of Coca-Cola and telling him that they hold a substantial stake in Pepsico, so maybe chill out with the competition a bit; or through explicit directives to contract with firms that they have stakes in. This would be straightforwardly illegal – an executive is required to look out for all of the shareholders, and cannot tunnel the assets of the company to other parties, just the same as they could not embezzle the company funds. The mechanism must be more subtle.

Anton, Ederer, Gine, and Schmalz (2023) argue that they have got it in hand. When firms become commonly owned, contracts become less based on performance pay. This straightforwardly makes the firm worse, obviously, but that’s okay – the effect on other firms’ profits can outweigh it. They show that, while it takes a bit for contracts to be renegotiated, greater institutional ownership leads to fewer incentives for profits. I have concerns about this, which I will discuss in the section on innovation, but this is in line with common ownership muting competition.

Now, finally, the big question. How much have markups risen by? There are a number of studies, largely based on event studies, which claim to find that common ownership increases prices. Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu (2018) is an early paper along these lines, which regresses common ownership concentration on ticket prices in the airline market.

However, these are just fundamentally not able to answer the questions they are trying to answer. The relationship between concentration and competition is not monotonic, and is consistent with many levels of markups and consumer welfare. You can find the reasoning in “On the Misuse of Regressions of Price on the HHI in Merger Review” by a pile of authors consisting of approximately every notable figure in empirical industrial organization. (It can’t be read as anything other than an exasperated reminder to anti-trust lawyers to stop running regressions when you don’t know what you’re doing). Both concentration and markups are jointly determined by the same underlying primitives. There is no causal arrow to draw from concentration to price.

Better than this, but ambiguous as to cause, is Boller and Scott Morton (2020). The inclusion of a stock in an index like the S&P 500 is well-known to increase the price of the stock. (The demand curves do indeed slope down). That in itself says nothing. What is interesting is that the inclusion of a stock in the S&P 500 causes the price of its competitors to go up as well. This is suggestive of something, at the very least. The trouble is that the price of the stock going up is consistent with both a change in conduct, and a change in efficiency due to (for example) increased innovations. My other concern is that, imagine there is a group of investors who are credit constrained, but have a generally positive opinion of all stocks in a given sector. A firm gets included in the S&P 500, which gives them a windfall – it seems likely that they would then spend it on similar stocks. Something must be going on, it’s just not clear what.

The very best study on markups and common ownership does not find that markups increased. “Common Ownership and Competition in the Ready-to-Eat Cereal Industry”, also by Backus, Conlon, Sinkinson and in reviews at Econometrica, is one of the best papers I’ve ever seen. They take a structural approach to answering the question. Rather than simply run regressions after events happen, they build a model of the economy from the ground up, and then simulate counterfactual scenarios.

Ready-to-eat cereal means things like Cheerios, Grape-Nuts, Frosted Flakes, and Cinnamon Toast crunch. Some of the classic work in demand estimation, like Nevo (2001) and Hausman (1996), has been on this. It is one of the “model organisms” of industrial organization work, as it features extremely detailed product information, is very concentrated, and each firm offers many varieties. For the purposes of evaluating common ownership, the four main firms all have different ownership structures, their ownership changed over time, and there were discrete events which changed the importance of different institutional investors.

I am going to largely elide the technical discussion, which is very difficult. (I have been informed that there will be a new draft out soon which tries to make it clearer – this is greatly welcomed!). What we want to know is the “conduct” of how firms compete. How much weight do they place on each other’s profits? The fundamental problem, going back to Bresnahan (1982), is that any response of quantity supplied to a demand shock is consistent with any given combination of conduct and marginal costs. Bresnahan’s solution is to rotate the demand curve, as when a substitute good arrives, and use that to identify conduct.

What Backus, Conlon, and Sinkinson do is, after recovering marginal costs, test how well different conduct assumptions explain the observed behavior. The one they find which best explains the facts is that institutional investors are not behaving like profit maximizers. They are able to reject the distribution of markups being any further than 30% from what a model where firms weigh only their profits would be. It is important to note, however, that they are concerned only with markups, which are the difference between marginal cost and price. The story is consistent with failing to find a technology which would reduce marginal costs, as in Anton et al.

The last bit of evidence on actual conduct is a bit of common sense. The implied change in behavior is absolutely enormous. We’d probably have noticed it. If there’s a massive change in what’s predicted about the structure of the economy, and we don’t see it, something’s probably off.

The softening of competition is only one side of the story, though. Innovation could flip this all on its head. Suppose that innovations require a fixed cost to discover, but can then be used by all firms costlessly. In a world where each firm is atomless and cannot affect the price at all, then no innovations would ever be found. No one would ever pay the fixed cost to find it. As we increase the market power of firms, we find that they will pay the fixed costs to discover more and more innovations, but less than what a monopoly would discover. This is why we grant patents.

There are two channels through which firms’ innovation affect each other. Following Bloom, Schankerman, and Van Reenen (2013), we think of there being a technology space and a product market space, with innovations affecting the firms close to each other. Technology space and product market space do not necessarily overlap with each other. Firms can produce products which use computers which have almost no substitutability, but benefit from the same technologies, like calculators and laser-jet printers. Bloom, Schankerman, and Van Reenen found that the technology spillovers were several times as large, in line with Jones and Williams (1998).

The direct evidence is unfortunately poor or indecisive. “Innovation and Institutional Ownership” by Aghion, Van Reenen and Zingales would seem to be perfectly suited, but as a note by Simeth and Wehrheim (2024) shows that it suffers from serious data issues and cannot be relied upon. The same Anton-Ederer-Gine-Schmalz team has working paper building off of the BSvR framework, which doesn’t find much of anything. They only find that innovation is increasing in technology spillovers and decreasing in product market spillovers.

We also have some less direct evidence. Roma Poberejsky (2025) argues that interlocking directorships, which create similar conflicts of interest as common ownership, increase the quality of innovation by preventing firms from unknowingly researching things which are too close to each other in technology space. She gets effect sizes which are surprisingly high, both to me and to Florian Ederer.

I would like to return to the point about the smoking gun. The lack of high-powered contract incentives is compatible with both positive and negative stories. On the one hand, it reduces their incentives to cut cost, but on the other, it increases their incentive to engage in prestigious but individually unprofitable R&D. This is especially the case if executives are risk-averse, which is exactly the claim that the authors of “Innovation and Institutional Ownership” argued was responsible for their results.

I am not able to calculate both the plusses and the minuses now. I humbly submit, however, that we cannot make sweeping claims about antitrust law without considering both halves. Looking at the effect on competition will find either a null or a negative effect, but it would be absurd to look at only that. It would be like looking at patents and considering only the markup, without considering how it endogenously leads to more innovation.

My goals for things to read and consider are the effect of common ownership on agency costs. We do not perfectly diversify the economy, because we need agents (the executive) to take non-contractible actions. I would be curious to see what the optimal portion of passive investors in the economy is.

A fascinating look at how "common ownership" can emerge within capitalism, driving up costs for consumers, but also increasing the incentives for innovation. I also wonder about the impact of transnational indices that bundle companies together across countries. Do they lead to firms in each country more aggressively lobbying for free trade policies?