The Gains From Trade Are Not The Gains From Trade

It is the diffusion of ideas which matter!

In July of 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy sailed up the mouth of Edo Bay to the capital, and intimidated the Japanese so that the following year, Japan agreed to open up to the world. Under the Harris treaty of 1859, multiple treaty ports were to be opened, and import duties were fixed at a low level. Prior to this, Japan was a poor, backwards, and autarkic state, paranoid of outsiders, and content to avoid any contact with the barbarians and their ways. Trade consisted of a few pittances exchanged with the Dutch, in a carefully isolated fort in Nagasaki, and nothing else. The shock led to the restoration of the rule of the Emperor (rather than the Shogun), and the development of Japan as an industrialized nation capable of making global war.

Bernhofen and Brown (2005) try and put numbers on the effects of trade. Key to their method is that relative prices under autarky are sufficient to learn the tradeoffs between goods that govern comparative advantage. Japan was a rare example of a country which was truly autarkic, thus allowing them to precisely answer the welfare effects of trade using relative prices and trade flows. Since we know what the comparative advantages are, it’s trivial to just calculate out how much welfare increased by. They estimate that opening Japan to trade increased welfare by 8 percent.

Yes, 8 percent. That is a level change, by the way, not a change in rate. How are we, then, to explain why Japan grew so much as a consequence of opening up to the world? The authors note, in defense of their method, that there had not yet been time for technologies spread across the border, (so the changes in trade flows represent the same comparative advantages), and that is the key to understanding things.

Trade isn’t about trade. It’s about ideas. Connections across borders lead to the flow of technologies and techniques and people, in ways that we often can’t measure, and it is that which leads to modern economic growth. Tariffs do far more than simply inhibit the transfer of goods, and the losses from them are far greater than other methods of raising taxes for that reason.

Trade did not lead to Japan booming, but it was openness to the world that did. Juhasz, Sakabe, and Weinstein (2024) show that economic growth couldn’t take off until technical knowledge was written in the vernacular language. Prior to the creation of the first Japanese-English dictionary, you couldn’t really learn anything about modern technology. In fact, not only were the books not translated, but many of the concepts lacked words entirely, and had to be created! (For details on this, I highly recommend this book review of Yukichi Fukuzawa’s autobiography, who really was a heck of a guy.) There is an unmistakable trend break with the publication of the first dictionary – and that is in logs! By 1887, Japan had reached the level of technical knowledge which Germany had had in 1870. It was an astonishing change.

Back to JSW, they can precisely measure how much technical knowledge has been codified because they’ve scraped enormous libraries of books published, and categorized them with AI. Growth did not take off until Japanese knowledge approached the level of the developed world, and far exceeded that of other developing countries. This knowledge varies by sector, which allows them to estimate the effects of knowledge on growth. And it had to be ideas, because nothing else explains it. Not trade, not a national bank, not the introduction of a parliament, not subsidies to industrializing firms, not railroads, not land tax reform, not the gold standard – nothing comes close to explaining the rise in Japanese production except that before they opened to the world, they didn’t know how to produce. (Page 5 of the paper includes the relevant citations for the claims).

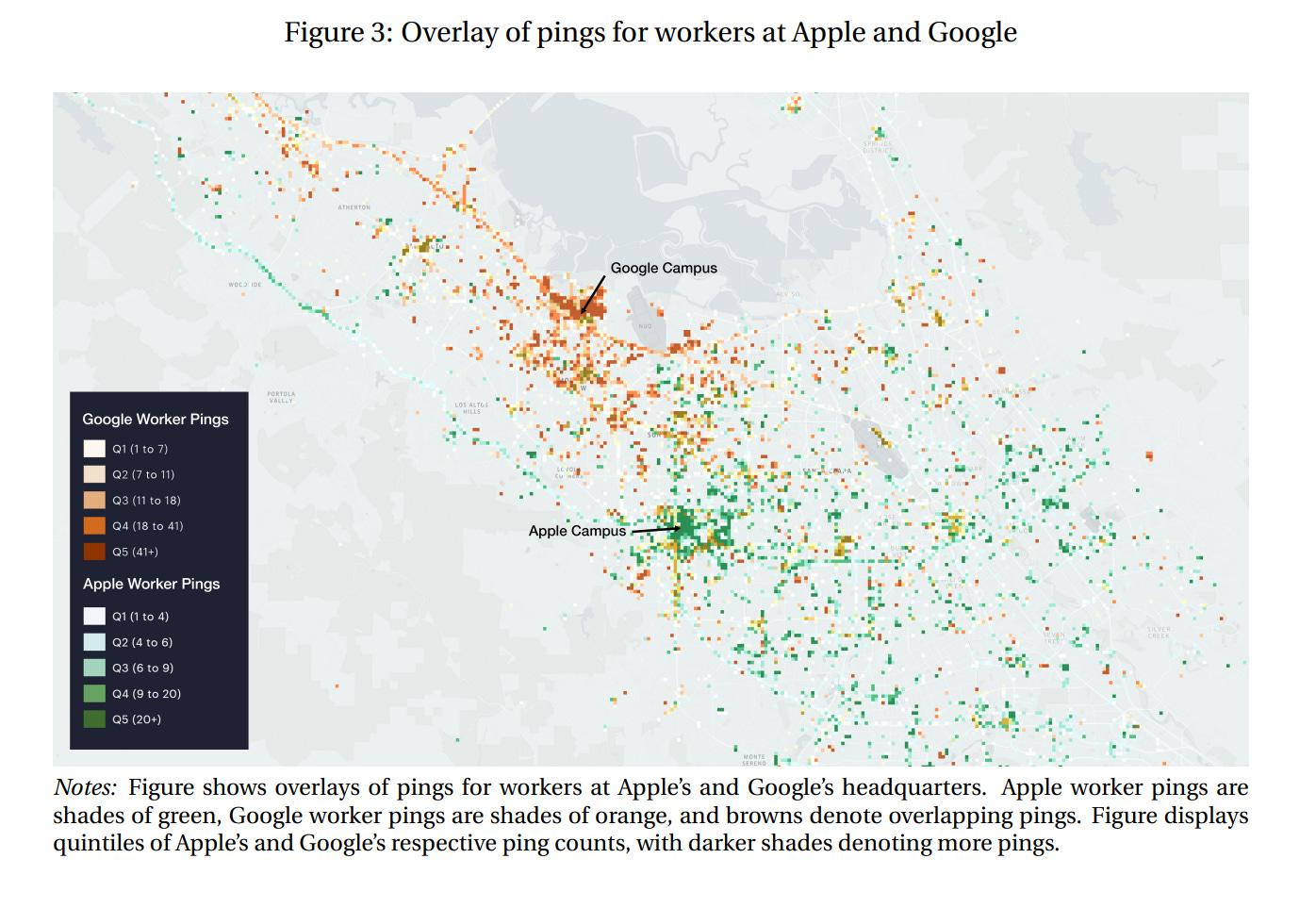

Other work has traced how idea diffusion is often due to chance meetings, rather than due to deliberate action. After all, if you could still arrange valuable meetings, then trade might reduce the opportunity costs of travel, but it shouldn’t have that large of an effect. Atkin, Chen, and Popov (2022) use detailed records of cell phone pings to track where the employees of major Silicon Valley firms live and work, and the effect it has on the patent filings of their employers. They can trace who works where from their location during the day – if someone spends their time in Google’s offices between the hours of 9 to 5, we might reasonably infer that they work there. The data looks something like this.

Employees live near where their employers are, so whether they meet employees of other companies (which they define as being at the same place at the same time) is a function of how close their employers are. Of course, companies might be co-locating for reasons other than meeting people, so they instrument by seeing how likely employees of a company in an industry which has never (not once) cited a patent in the industry that first employee works in, are to be in the same place at the same time. They show that these face-to-face meetings have an enormous impact on patent citations. The magnitude is such that eliminating a quarter of meetings would reduce patent citations by 8 percent, which is considerably larger than prior estimates on the effect of being in a different city entirely. Much of this is due specifically to unanticipated, serendipitous meetings, which is precisely the sort of thing that foreign trade enables.

An example. The United States exports cars to Japan, and imports them in turn. This gives us gains from increasing variety, as in Krugman (1980), but these gains probably aren’t all that large. If we had to only rely upon American cars, we would suffer only a small loss. Consider what will happen to the transmission of ideas. To oversee the importing and exporting, representatives of each company send employees to the other country. While there, they meet at technical conferences, they discuss ideas, and they form rapport with employees at other companies. Much less of that happens if trade had not lowered the cost of putting your employees abroad.

There is a case for tariffs. While they are beggar-thy-neighbor, and it is doubtful that we would want to, as a matter of justice, transfer from the poorest countries in the world to the richest, tariffs transfer part of the burden of taxation onto foreign consumers. Thus, the optimal tariff is positive – or at least, it would be, if trade were only trade in goods. Since trade generates massive positive externalities, taxing it would be madness.

We must, however, answer whether the externalities from trade are greater or less than the externalities from labor. People who work, especially at the top of the income distribution, have positive spillovers onto other people, through the ideas that they find or companies that they form, as I discussed on the blog recently. The losses from a tax on trade will tend to be greater than a tax on income or consumption generally.

For simplicity, we shall assume that we are taxing the personal consumption of people (an income tax works out to the same thing, but with the unneeded possibility of shenanigans in how we treat labor income. Income taxation affects labor supply through the channel of making your hours of work buy less stuff, so it hardly matters whether we tax the labor or the things we buy). Assume also that the elasticity of labor supply with respect to taxation is the same in all countries. Ideas are generated as a function of working, or of interaction through trading, and we shall say that both are equally important. We can see immediately that tariffs are simply a subset of consumption taxes, and that tariffs reduce both channels of idea transmission. Holding revenue constant, the reduction in ideas found must be greater, if the full burden falls upon the US consumer. As we have more of the tariff fall upon foreigners, then the reduction in trade will resemble that of the response of consumption when we placed a consumption tax on ourselves, until at the extreme the effect of the tariff is the same as a consumption tax. Anywhere in between, the tariff would be strictly more distortionary to the creation of ideas than a consumption tax. If ideas are generated by people working globally, then a tariff would always be worse.

As I have been arguing, the value of ideas is vastly greater than any static gain from better taxation. That is the great advantage of international trade, and our present administration scorns it to the loss of us all.

This is also a great argument for increasing funding in universities. Also a great argument for reducing prohibitive zoning laws in cities to increase density. Also a great argument for how policy makers underestimated the effects of social distancing policies during COVID. We should probably start considering anxiety disorders as more than a mental health crisis, but also an economic and innovation crisis.

I like the post a lot. I think the thesis is clear, compelling, and underrated.

I also want to register that I am very skeptical of the 8 percent number from Bernhofen and Brown, and from similar types of studies. These trade models make very restrictive structural assumptions that would break down as a country switches from some trade to absolutely no trade. For example, Japan has no oil! The costs of no trade vs. very little trade will be huge because in a world with very little trade, Japan can still access oil. My understanding of these trade models is that they do not make this prediction.

I am also curious how well these models help us understand high value trade where a single product moves through multiple countries during the assembly process.