The High-Wage Thesis isn’t even wrong!

Edit 4/27/25: I believe that this blog post is wrong. Gains from ideas are not fully captured.

A long-running theory in economic history is that the cost of labor had a massive impact on the Industrial Revolution. Places with higher wages relative to capital, the theory runs, were far more inclined to invest in finding new labor saving technologies. England had higher wages than the rest of the world, so it was the first to invent labor saving machines, such as the spinning jenny, the water frame, and the mule. (All of these being apparatuses for more efficiently spinning thread). This was most forcefully advanced by Robert Allen, in his book “The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective”.

Most of the argument has been about whether the facts are true. The trouble is, it doesn’t even matter if the claim is right or wrong. The theory does not follow from its presumptions. Paul Samuelson writes here about the purported tendency for innovation to be labor saving. If we are in a world which tends toward equilibrium, the marginal product of labor and capital are the same. There is no such thing as a more expensive factor of production. To illustrate, imagine Country A, in which candles produce one hour of light, for one dollar. In Country B, candles produce two hours of light for two dollars. The marginal productivity of the two are identical. Will Country B produce a lightbulb any faster than Country A? Both face identical costs, even though the denominator has changed.

And there is evidence that the high British wages were indeed due to differences in productivity, and thus the marginal cost of labor was the same everywhere. In “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed? Evidence from the Cotton Mills”, Gregory Clark tries to explain why textile production remained concentrated in Britain until at least the 1900s, despite paying wage rates multiple times higher than continental Europe, India, or China. After systematically eliminating every possible technical advantage England could have had, he is forced to conclude that differences in cultural attitudes led to large differences in per person productivity. Even in the simplest task, such as replacing spools of yarn after they had been woven, the English worker did more, on average, and thus earned more. We should not be so quick to assume that, just because it “costs more”, it is actually more expensive. These are quite different things!

Innovation occurs where it does for technical reasons. Some problems are easier to solve than others. If they happen to economize on labor, this is mere coincidence — it just happened to be that the problems which were easiest to solve saved labor.

Back to Samuelson. He writes: “For the most part, labor-saving innovation has a spurious attractiveness to economists because of a fortuitous verbal muddle. When writers list inventions, they find it easy to list labor-saving ones and exceedingly difficult to list capital-saving ones. …That this is all fallacious becomes apparent when one examines a mathematical production function and tries to decide in advance whether a particular described invention changes the partial-derivatives of marginal productivity imputation one way or another. …

…

We have the unfortunate tendency to use labor as the denominator in making productivity statements. Any invention, whether capital saving or labor saving, just by virtue of its definition as an invention rather than a disimprovement will, other things being equal, result in more output with the same labor or the same output with less labor. That could be said with any factor substituted for labor. But we know how difficult it is in a changing technology to get commensurable non-labor factors to put in the denominator of a productivity comparison. So we tend to concentrate on labor. and then we fall for the pun, or play on words, which infers a labor-saving invention whenever there is an invention!”

If the inventions were indeed labor-saving, this is mere coincidence. There’s evidence to suggest they weren’t particularly labor saving. This always gets brought up, but English patents of the time very rarely mention saving labor as a reason for the invention — saving capital is more common. (Because this is a blog, I will not track down the citation. It comes up a lot, especially with Mokyr).

Is there some way to rescue the high-wage hypothesis? Perhaps, but it would require us to take a rather strange view of innovation. If innovation is simply something which happens randomly as you use an input, then countries which use a greater input of capital will find more innovations. This is simply restating the point, however, that innovations are related to where technological progress is easier to find – there is no reason to think that innovations which economize on capital at the cost of labor must necessarily be always more expensive. Moreover, this can explain microinventions, but not macroinventions. Tinkering with a machine will plausibly lead to improvements, and the more machines are tinkered with, the more inventions. It has no plausible reason to lead us to inventing entirely new machines. Did the locomotive arise from mechanics tinkering with steam engines?

If this is the case, then the story can focus on the low cost of coal. Here we are not focusing on the relative cost as compared to labor, but on the absolute cost of coal. Perhaps certain iterative improvements in the steam engine, under imperfect capital markets, only become worthwhile in a world where coal is very cheap. Much of the Industrial Revolution literature is arguing against “Why not in China”; Ken Pomeranz writes (“The Great Divergence”, pages 63-64 and 184) that the centers of coal production were in the North, far away from the population centers, and either way their mines tended to be dry. The early steam engines, such as the Newcomen engine of 1712, were used to pump water out of mines, and were really only profitable at the pithead, where coal could practically be shoveled straight into the machine. “…Pit-head steam engines often used inferior “small coals” so cheap that it probably would not have paid to ship them to users elsewhere, making their fuel essentially free.” (p. 68)

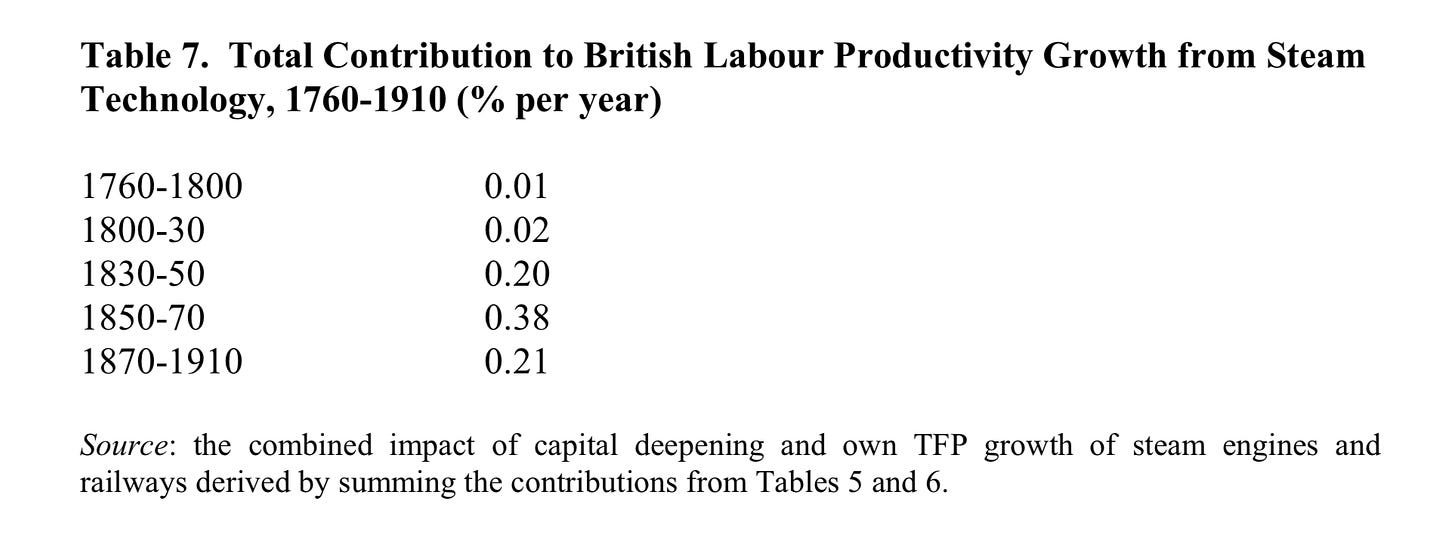

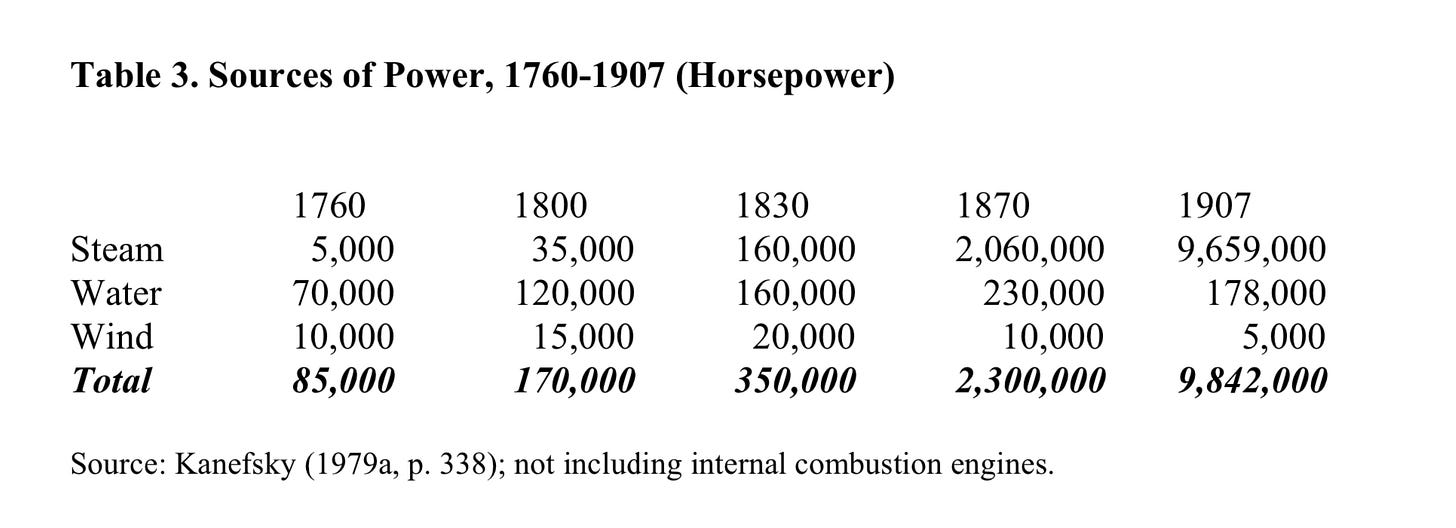

Of course, the problem with any story emphasizing coal is how little the Industrial Revolution — the first one, at least — actually had anything to do with coal. It wasn’t until after 1830 that steam power surpassed water power, according to von Tunzelman. (p. 67 of “The Great Divergence”). Drawing from Wikipedia, by 1800 steam engines produced less horsepower than *wind power*, and a mere tenth that of water power. The spinning jenny was invented in 1765, and the spinning mule invented by 1780, and they spread *fast*. They clearly would have existed in the absence of steam. The contribution to total factor productivity growth was minuscule, according to this paper from Nicholas Crafts. Attached below are several tables illustrating this. Clearly, a coal-based explanation is inadequate — the higher wages inducing innovation is needed for the first 70 years, and we have shown that that explanation is theoretically unsound

.

An alternative construction of the high wage hypothesis could say that if everyone anticipates the cost of labor will increase in the future, thus necessitating more capital usage in the future, this could bias technical progress toward labor saving. Samuelson identifies this idea with Fellner. This is saving the hypothesis by completely changing it, however. This is concerned only with the future expected course of the price of labor, and not with its level at all. That England had higher wages does not matter in the slightest. Indeed, if anything, the price of labor went down during the Industrial Revolution! The Fellner hypothesis in the English context would militate *against* the English preferring labor-saving machines. It is far more plausible to think that people had no consistent expectations of the future course of prices.

Worse still, it is completely powerless as an explanation. We have no way of assessing the beliefs of 19th century industrialists as to the future course of wages, nor any reason to think they should be higher in some countries over others. Being unable to observe people’s attitudes, it is an explanation only by tautology.

In truth, coming across this has made me concerned about economic history as a discipline. We have spent years arguing about this — to find that it has been decisively shown to be irrelevant 60 years ago fills me with fear that we are wasting our time on other theoretically unsound ideas. Certainly I cannot think of anything else like this — but of course, were it so obvious it would be discovered. It may be profitable to examine the theoretical underpinnings of the Industrial Revolution.

An invention that saves capital is conceivable.

Arguably wireless technology saved on the capital of telegraph lines.

A lot of inventions are making something new that didn't exist before. An x-ray machine give the doctors better outcomes, not less work. Modern medicine seems to take a lot more work than just handing out leaches and mercury.

A labor saving tech is one that would be useless if you had an infinite number of slaves that magically needed no food and never disobeyed.

"English patents of the time very rarely mention saving labor as a reason for the invention" that's partially because saving labor was seen as a bad thing.