How important was the Columbian Exchange for Europe? Much ink has been shed discussing the costs and benefits of colonialism – indeed, some minute quantity of that ink has been shed on this very blog. I want to focus on a benefit which required no expropriation – the potato.

China and Europe had vastly different political trajectories in large part due to their crops. Europe grew barley, wheat, and other such grasses. China grew rice. Wheat requires far more land than rice does to grow an equivalent quantity of calories — figures here — although once the additional physical exertion is taken into account, the advantage of rice drops considerably. They can support more or less equivalent levels of sustenance, just at vastly different densities. On account of the different population densities, Chinese emperors could raise larger armies. European armies focused on a core group of very heavily outfitted knights, with armies being otherwise much smaller. This seems to follow from a sort of Alchian-Allen theorem – if a fixed cost is applied to both luxury and regular commodities, the relative consumption of the luxury good increases. Analogously, fortifications were relatively more powerful in Europe than in China, because states were smaller and could not reduce the fortifications cost-effectively. Castles could be kept with a skeleton force of men – they weren’t there to guard an area, they were there to guard a contingent of men, who would ride out to ambush foragers. Chinese fortifications tended to be rammed earth walls guarding larger towns.

One wonders if there were multiple equilibriums with the level of fortifications. There was surely learning by doing in the construction of the fortifications – true castles were extremely rare in China, and built mainly in places far away from the central government. I wonder if, in a world where anarchy lasts longer, fortification is improved far enough to cause a permanent break away from centralization. It wasn’t until gunpowder came about, and the strongest lord could knock down any wall, that modern states in Europe really began. A possibly underrated factor is that China is considerably seismically active than Europe. If rammed earth is cheaper to construct, it may pencil out that fortifications shouldn’t aim to be as permanent. I don’t think earthquakes were sufficiently frequent, but such a hypothesis would be extremely interesting to explore.

But enough of such speculations – they are besides the point of this paper, by Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian, which is more narrow. Nunn and Qian want to show the effect of the potato on urbanization, which they find to be absolutely massive, accounting for a quarter of the growth in population and urbanization in the Old World between 1700 and 1900. It is not implausible that, without the potato, economic growth would have been slowed down decades.

The potato is a wonder food, containing almost all of the vitamins needed to sustain life. (The rest can be made up with dairy). One can live off of – boring though it is – a diet of potatoes alone, as many Irish peasants did, until they didn’t. They were regarded as noticeably healthier in appearance, and taller than English peasants. (Their poverty consisted mainly in consuming a different consumption basket – they were worse dressed, and lived in worse homes, but were considerably better fed. Consult Mokyr’s “Why Ireland Starved” on this point).

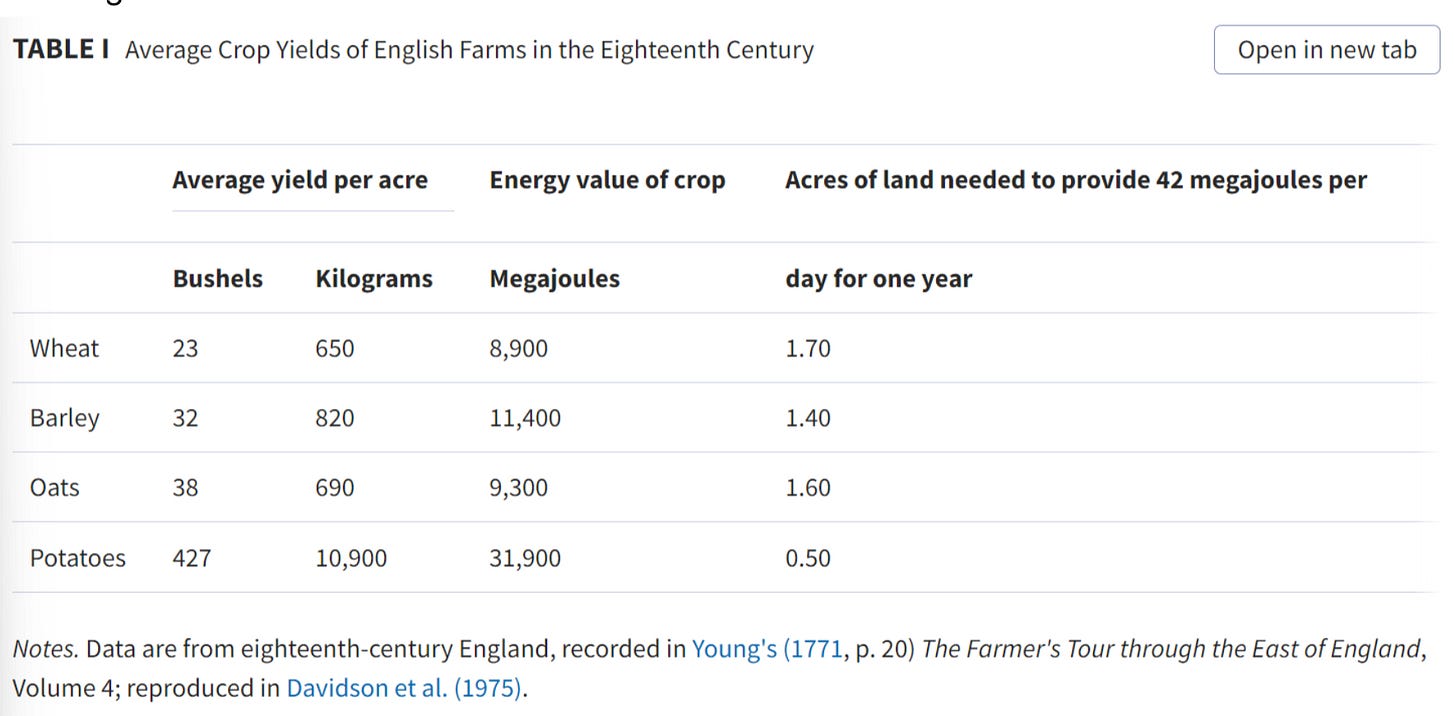

Not only is it nutritionally sufficient, it is considerably more land efficient. Reproduced below is table 1 of the paper. You could get three times as many calories out of one acre of land than a similar acre of cereals. One acre of potatoes and one milk cow was enough to feed a family of six to eight.

Now, potatoes were considerably harder to harvest, requiring 2 and a half times as much labor input. This still puts the potato ahead in raw calories generated. The potato is also considerably harder to seize than cereals, which are harvested in one manic season, and then stored. Potatoes take a long time to dig up – you cannot swoop by and steal them. They can be fed to livestock with no processing whatsoever. Indeed, a substantial portion of potatoes became fodder for pigs.

But how do you show that it was the potato which was actually responsible? How do you check for omitted variables and reverse causality? The authors use a geocoded map of climatic suitability as a source of exogenous variation. Each cell is a 56 by 56 kilometre square. Places which are very well-suited for the potato are both more likely to adopt it, and have a greater intensity of adoption, and become more urbanized. This is a break in the pre-event trend, which was flat.

This effect is robust to many alternative specifications and controls. I quote, “These include legal origin, identity of the colonizer, the prevalence of disease (measured as distance from the equator and potential prevalence of malaria), distance from the coast, a history of Roman rule, the prevalence of Protestantism, being an Atlantic trader, and the historical volume of the slave exports. In addition, we show that we obtain similar results when we examine variation across countries within continents. Together, the results suggest that it is unlikely that our findings are simply capturing other historical determinants of economic development, including those factors that led to the divergence of Europe from the rest of the world.” (p. 5)

They additionally show the micro-evidence for why it would lead to an increase in population. Height, especially in the pre-industrialized age, is closely connected to health. Within France, enlisted soldiers had their heights taken. Places which adopted the potato had taller soldiers than those who did not – an increase in average height of half an inch, when comparing a completely suitable village to a completely unsuitable village. The dataset contains 13,000 individuals, from 1658 to 1770. The data is from Komlos 2005, which I am including here in case you are interested in using it too. (This is so clearly an addition from the referee reports, by the way. I would bet on it).

It is excellent work, and the sort of thing that makes me proud to be an economic historian. The toolbox of the economist allows us to answer questions which the historian could only theorize about vaguely. There is simply no way to answer this question without econometric testing. Statistics is our friend. I offer the next paragraph, though, as consolation for the traditional historian.

Nunn and Qian attempted to continue this line of work on the potato in a paper with Iyigun. I mention it only in the interest of completeness – I thought it was importantly wrong, and it is perhaps best that it remains a working paper seven years on. They want to see if it has changed the frequency and intensity of conflict, but alas, in something all too painfully familiar to any economic historian, the data is simply too bad to work with. The measure of conflict is not comprehensive – it does not pick up on the endemic raiding and violence between local barons. Moreover, if battles became half as frequent but three times as large, the data set would pick that up as a fall in the intensity of conflict. (And heaven help you if you try and impute the number of men in a battle before about 1750). In an ideal world, traditional historical methods create theories, which can then be subjected to statistical rigor, all the while checked by normal economic theory asking “does this make sense?”

The paper is “The Potato's Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence From A Historical Experiment” by Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian. If you read it and find this exciting, consider being an economic historian. We get to ask – and answer – the coolest questions.

Also how it got popular. Frederick the Great wanted the Prussian people to eat it, because somehow they already noticed it is healthy. But they disliked the novelty, especially when promoted by the king. So he set up royal potato fields with armed guards, and told the guards to do not notice anything. This convinced the people this might be something good, if it is guarded and denied to them, and stole it. There is a lesson lurking here, I guess.

Potatoes have much more water inside than cereals so they are far heavier per calorie, more fragile and they spoil pretty fast so they were not an internationally traded commodity like wheat was but they were amazing as a locally eaten subsistence crop.