The Primacy of Reallocation in Economic Growth

Productivity growth need not happen where the technology is changing

When we consider why countries grow, we often take for granted that it occurs due to improving productivity in the sector which is changing technologically. The Industrial Revolution was a time of great improvements in technology in the industrial sector – steam engines! the spinning jenny! – so it is strange to think that, actually, most productivity growth was coming from agriculture. This pattern repeats itself multiple times throughout history – growth occurred from reallocating unproductive workers from agriculture to industry, but not necessarily through fast growth of the productivity of industry. We should expect that small increases in manufacturing productivity should lead to much larger increases in total productivity.

Let’s say that we are in a two sector economy, consisting of agriculture and manufacturing, which will stand in for everything not agriculture. Land has decreasing returns per person working the land – at least along the relevant scales – as does manufacturing. The efficient solution is that everyone leaves agriculture until they reach the point of constant or increasing returns, but this will not be reached on its own. If a worker would move from agriculture to manufacturing, part of the gain would fall upon his fellow workers, who would see rising wages from being able to work more land. Because of this, an inefficiently low number of workers will move out of agriculture, and wages will be persistently higher in manufacturing. Everyone would benefit from workers being reallocated, but it is privately optimal for no one to move. A productivity shock to manufacturing pushes some people’s benefits to moving above the foregone, and causes them to move. Productivity increases in both sectors, despite technology only improving in one.

The key assumption is that land is being held in common, and it is divided up among other people if someone leaves. If we grant a property right to each person, and assume frictionless markets, then we would reach the efficient solution because each landowner can capture the value of the land when they sell it. The market for land in 1600s England was plainly not frictionless, though. People had very limited access to credit, and even if they did have access to credit, negotiations are costly and need not lead to the efficient outcome. The Myerson-Satterthwaite theorem is quite powerful – the optimal strategy for individuals is often to commit to not making some mutually beneficial trades, so that you can get more of the surplus. This shows up even in seemingly frictionless settings, like bargaining on Ebay.

We could also modify the model by claiming that there is some cost to making the move, and that there are either decreasing returns to manufacturing, which will lower the wage until we reach equilibrium, or the cost to move for an individual is idiosyncratic. In this world, we would predict that the wage in the manufacturing sector is persistently higher than in agriculture, and that policy subsidizing the cost, or removing barriers, is greatly welfare-enhancing.

The gains from reallocation can be massive. Restuccia, Yang, and Zhu (2008) write: “In 1985, the average gross domestic product (GDP) per worker in the richest 5% of the countries in the world is 34 times that of the poorest 5%. This is an enormous difference in aggregate productivity. However, the labor productivity difference in agriculture is even larger: GDP per worker of the richest countries is 78 times that of the poorest countries. In contrast, the difference in GDP per worker in non-agriculture is a factor of 5. Despite very low productivity in agriculture, the poorest countries allocate 86% of their employment to this sector, as compared to only 4% in the richest countries.” So, let’s see how reallocation led to economic growth in the past.

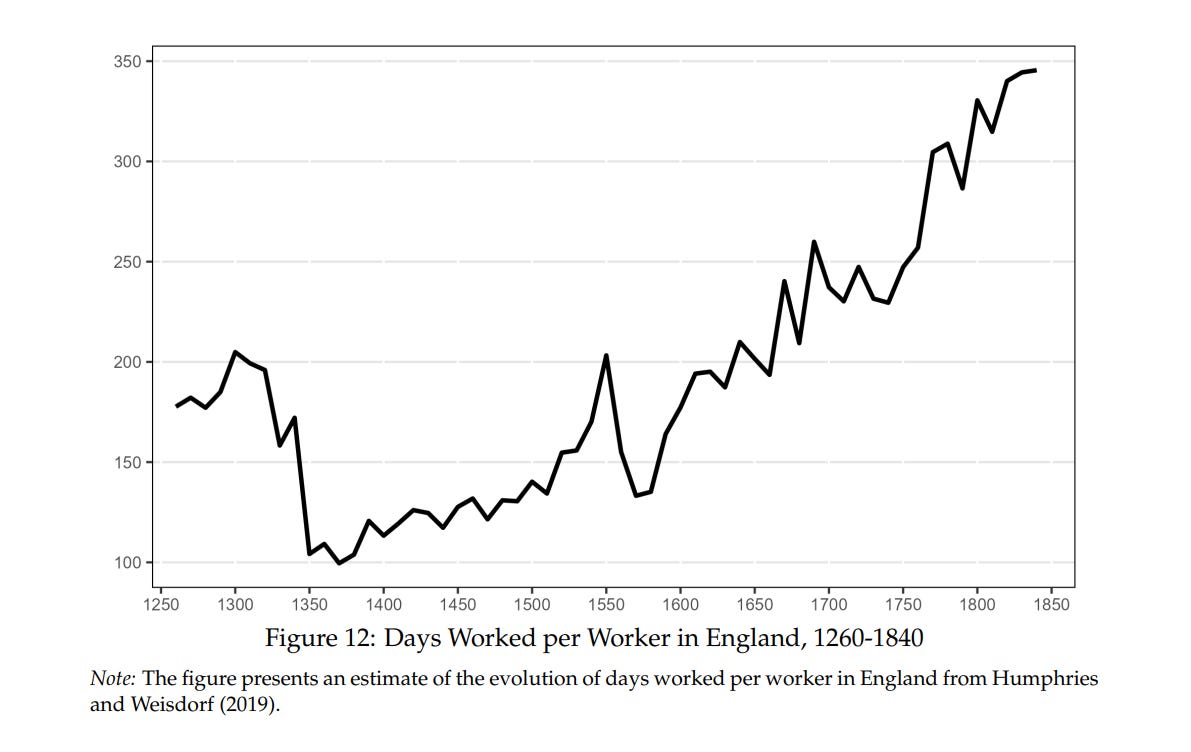

The Industrial Revolution in Britain has surprisingly low levels of total factor productivity growth, especially after adjusting for the increase in hours worked. (As people got more possible trade goods, they began to work more hours. In my personal opinion, it is underrated how much of economic growth is due to gaining access to new goods, rather than from making goods cheaper. I think it goes some way in explaining why we still work so much, along with jobs becoming increasingly pleasant. But enough of speculation, back to economic history!)

Bouscasse, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2024) estimate a gain of 2% per decade between 1600 and 1800 and 5% per decade between 1810 and 1860, with no sustained productivity growth before 1600. It did go up when people died from the Black Death, however, and went down again when England was repopulated, decisively showing decreasing returns. Their basic method is to take the period 1200-1600 as simply being a slide up and down a demand curve, and then use that to estimate how much the demand curve got shifted out by productivity, taking into account the massive increase in population.

Pol Antras and Hans-Joachim Voth (2002) independently calculate TFP growth, using input and output prices. To measure the productivity producing porcelain, we don't have to observe quantities, but can simply measure the ratio of output prices to input prices. If it increases, we can infer that companies got better at producing the good. Obviously, it can be biased if there is some factor we cannot observe, like “entrepreneurship”; but to some degree, when it comes to historical data you just have to throw up your hands and do the best you can. They come to small estimates of productivity increases, in line with Crafts and Harley, who were the original expositors of the pessimistic view of the Industrial Revolution.

I am not denying that technology did not improve. In fact, that’s a critical part of the story. Rather, the small technological improvements are what unlocked much larger gains from reallocation. To illustrate this, the spinning jenny increased the productivity of a worker about three times over – they could spin three pounds a day, instead of one. Yet, between 1770 and 1815, the industry grew 2200%. (Go to page 68). There were obviously other technological improvements, but there is absolutely no way it grew that much without taking in far more people.

The United States and Germany took a similar path to industrialization. Stephen Broadberry argues that they overtook Britain in manufacturing not by changing the relative level of productivity, which remained lower throughout the period of catching up and overtaking. From 1870 to 1930, the percentage of workers in agriculture fell from 50% to 21% in the US – in Germany from 50% to 30%. The UK, having already gone through its great shift, could not keep up. Hornbeck and Rotemberg (2024) uses actual firm-level data to measure misallocation in the United States, and how much it was reduced by railroads. They come to absolutely gobsmackingly large estimates – a whole 25% of GDP growth was due to railroads reducing misallocation across firms.

Also in the United States, Costinot and Donaldson study the gains from economic integration in agricultural markets. Their method is incredibly cool – they have a database down to the level of fields, not only of the observed productivity of the crops which were grown on it, but of the potential productivity of everything which could be grown on it. People have a preference for a mixture of goods, so in a world of prohibitively high transport costs everyone would have to grow their preferred mix of crops, regardless of how productive it would be; while in a world without transport costs, fields would produce only the crop they are best suited for. Armed with this data, Costinot and Donaldson can calculate how far from optimal crops were, and how much of observed growth is due to technological change, or due to better products. They estimate that 80% of growth between 1880 and 1997 occurred due to growing the right crops, not due to productivity improvements in how we grew the crops.

China, during its great industrialization, took a similar path. Brandt, Hsieh, and Zhu point out that, while TFP grew by 6.96% per year overall, the nonagricultural sector grew only 4.95% per annum. Agriculture’s TFP grew by 6.75% per year. TFP was growing – in contrast to the time of Mao, when growth occurred only due to additional investment and a rise in human capital (see Zhu (2012) for this), with total factor productivity actually falling by 1% per year – but this was due primarily to reallocation. Over 200 million people moved from the countryside to the city.

It is possible that the increase in productivity is not due to a technological change leading to people leaving agriculture, rather than people in an inefficient economy leaving the less productive sector. However, this does not line up well with the facts. Breaking up the period studied by Brandt, Hsieh, and Zhu into 1978-88, and then 1988-04, shows that most of the people moving from agriculture took place during the first period when the government reformed the hukuo system, and was responsible for half of all growth, while in the second period agricultural unemployment fell by much less and reallocation was responsible for less of growth.

China is an ideal example of the simple model I sketched out at the beginning. As predicted, wages are substantially higher for industrial workers than for agricultural workers when the reason for disequilibrium is a heightened cost to move. There has been some criticism of the story, notably from Ye and Robertson (2017). I largely don’t buy their criticisms, though – much of it is dependent upon adjusting for differences in human capital, and I do not believe that their measure of human capital actually maps onto real differences in ability. The other half of their criticism is that we cannot assume constant returns, but must instead assume declining returns as more people go into industry. I’m not convinced that this need be the case. However, I feel I must in good conscience mention it.

There is still much to be gained from reallocation across sectors. If people’s labor in agriculture has a marginal value of zero, then being able to produce anything – anything at all – would be an improvement. I believe this to often be the case in agricultural regions. The amusingly titled paper “The Continued Existence of Cows Disproves Central Tenets of Capitalism?” explores why people in India keep cows and buffaloes if, valued at prevailing market wages, the return to keeping them is incredibly negative. Only if you say that the marginal value of working more is zero do you make it economically sound. If markets are uncompetitive, and excess farm workers are being kept care of by their family, then we should expect fewer changes in labor supply in response to shocks, and we should expect the number of people in a family to affect labor usage. This is what Merfield (2023) finds – small landholders lack off-farm opportunities and are wasting away in inefficient jobs. Hornbeck, along with Suresh Naidu, has a paper on the 1927 Great Mississippi Flood, which found that places which flooded had many more people migrate out, and that the change in the availability of cheap, somewhat unfree labor led to the use of modern technologies.

A wedge like the hukou system can also come about from subsidies. In India, the massive subsidization of farmers keeps farmers from moving to cities where they would be more productive. Farm subsidies account for 20% of farm income, and 2% of GDP. Interestingly, many of these subsidies are in the form of input subsidies, which in a world with credit restraints can improve welfare. Chakraborty, Chopra, and Contractor (2024) estimate the effects of totally removing farm subsidies, and replacing them with a neutral monetary transfer. They find that it would raise total welfare, and reduce misallocation by 16%. Duranton, Ghani, Goswami, and Kerr (2016) argue that misallocation across districts is as important as misallocation within districts. In other words, the losses from people being unable to move to the places they could earn the most is as large as the losses from efficient firms. Given the profound misallocation among firms (see, for instance, Bloom et al (2013), and many other works). In the Philippines, the government instituted a massive land reform and managed to do everything terribly. They put a cap on landholdings, redistributed the land, and then barred people from selling. Adamopoulos and Restuccia (2020) found that, because people were disincentivized from migrating, agricultural productivity fell by 17%.

The natural implication of this is that immigration might be even better than you think. After all, there’s no reason to restrict ourselves to moving from sector to sector within a country. People emigrating, especially from places whose primary economy is agriculture, should raise wages in the home country. Even immigrants who are moving to work in agriculture raise productivity, because now they are being paid their marginal product. In future work, I will look at the effect of emigration opportunities on wages in Britain, but that paper is in the works and will take a bit. Until then, let this be a summary of what I know and think.