The Mexican drug cartels are full of bad dudes. They’ve killed tens of thousands of people, they engage in extortion rackets and corruption, and are substantially responsible for Mexico’s disappointing economic development. The drugs are often defective and dangerous, being cut with other drugs. The drug trade brings shame and infamy to everyone involved, from the manufacturers to distributors. One would think that the drug trade is just fundamentally bad, and will always make the world worse.

Al Capone was a bad dude. Lots of bootleggers were. They shot each other, they shot cops, and they shot innocent bystanders. The products they sold were often cut with methanol, leading to thousands of poisoning deaths. The whole thing was a sordid business, and it brought discredit to everyone involved. One would think that the alcohol trade was just fundamentally violent and bad.

But this is clearly wrong. The makers of Coors and Budweiser are not having gang battles in the streets of Chicago. Instead they are perfectly ordinary businessmen, manufacturing a perfectly ordinary product. Alcohol is indeed harmful to one's self, but it is nowhere near as injurious to the fabric of society as you would have thought during prohibition. What does this tell us?

When things are illegal, the people who do end up doing it are worse. If you simply look at the harms to society of something while it is illegal, you will have an exaggerated estimate of its harmfulness. This extends really broadly! Indeed, it likely extends far more broadly than you would be comfortable thinking about.

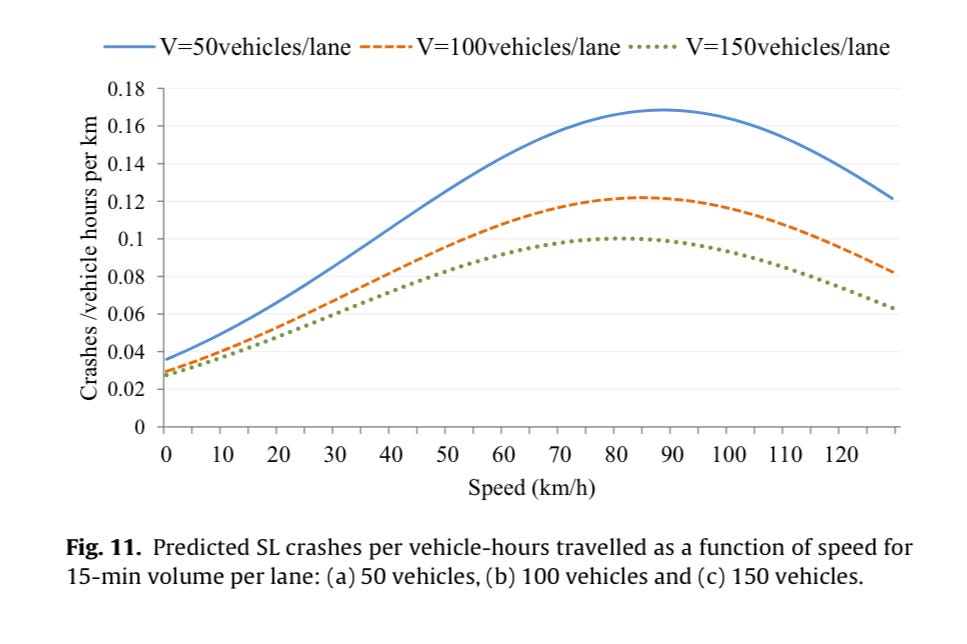

It leads us to overestimate the harms from speeding, for one. The people who choose to drive faster than what is legal are also just more reckless and less attentive people, beyond just the heightened rate of speed. Higher speeds increase the intensity of crashes – that much is obvious – but within the normal bounds of driving they need not increase the risk of crashes in and of themselves. Higher speed limits can actually reduce the rate of crashes.

Beyond simple selection, when people are traveling at different rates of speed, a higher average rate of speed means fewer cars pass each other in a given distance. Most event-studies do disagree, and find that reducing the average rate of speed on a given road does seem to reduce accident rate, however. My point is that you have to have study designs which can plausibly measure it. Simply saying that “so and so percent of people were speeding at the time of the crash” is entirely inadequate to answering the question!

This sort of selection can also happen in the other direction. People who are attentive to the news and health-conscious tend to be richer, better educated, and healthier anyway. Correlations are strengthened by people learning about them and changing their behavior to include them. The connection between breastfeeding and childhood outcomes is by now not only the result of breastfeeding being correlated with other positive traits, but by people learning about the connection and non-randomly altering their behavior. Despite the fact that better evidence shows no effect, it is still sometimes recommended, and a naive look at correlations will mislead. Encouraging something as a positive trait will lead to a biased view of its benefits, just the same as discouraging it will.

Emily Oster has done research demonstrating the selection, as it happened. In 1993, a pair of studies came out in the New England Journal of Medicine arguing that taking Vitamin E reduces mortality from heart disease. Now, these studies were (as is often the case in medical journals) spurious associations from observational data, but they made their way into popular media and official health recommendations. Randomized controlled trials – where some people were given placebo vitamins, and others weren’t – found that Vitamin E supplementation, if anything, increased the risk of heart disease, and so the health recommendations changed in 2004. During the time when Vitamin E was recommended, though, the association between it and less heart disease actually increased. This was driven entirely by the people choosing to do that behavior having better health habits generally. For example, people before the period were .7 percentage points more likely than average to smoke. Afterwards, they were 4 percentage points less likely. The whole connection was spurious, but it was made real by people’s expectations.

I am compelled by honesty – and enabled by a lack of good sense – to mention that, for this very reason, we likely overestimate the harmfulness of childhood sexual abuse, or childhood sexual contact. Because most abuse occurs within the family, both perpetrator and victim are genetically related to each other. Given the fact that all behaviors have a substantial genetic component, we cannot isolate what the effect of the behavior is, compared to the shared genes There is also ordinary non-random reporting. I’ve no doubt that cases of violent rape are far more reported than the fumbling explorations of siblings. It could also be due to other elements of a poor upbringing which are correlated with abuse. We cannot tell the magnitude of the bias without further study, but any reasonable estimate would tell us that it is quite large. Spanking has a similar dynamic, with an additional complication that spanking is itself caused by bad behavior. We cannot plausibly control for all things, so spanking (so long as it is done more by worse people) has harms likely biased upward as well.

I hope to have shaken you out of an easy confidence that the things we think are bad now are really all that bad. Harms are often contingent, and socially constructed. Something may be benign in one culture, and deeply hurtful in another. Scott Alexander discusses the idea of a hyperstitious slur cascade. A hyperstition is something which is true, only as long as people believe it is true. If enough people believe a word to be a slur, for example, then the only people using it are the ones who darn well intend it to be a slur. If I went and said that word to people who had no idea of its significance, they would simply be confused. There is nothing in and of itself bad about lifting up a veil and seeing what is beneath, but it is a massive problem if people believe the Holy of Holies is beyond it! Harm is not simply objective pain, but includes the foiling of people’s wants and desires, and these wants and desires are shaped by cultural expectations.

Imagine a world in which circumcision is regarded by most people as a surgical procedure of no significance whatsoever. Some people disagree, and consider it ipso facto abusive. Circumcision is fundamentally harmful. It is abuse and mutilation. They find a study with a false positive – being circumcised predicts negative outcomes - and so the recommendation goes out that if you want to avoid your kid being harmed, you mustn’t circumcise them. Those most likely to be successful stop circumcising their kids, and it becomes a behavior done only by the low, the poor, the dirty, and the contemptible. Do you not think that some people would think on their circumcision with shame? That they would find themselves profoundly harmed by it? And that nothing physical is different, only society’s view of it?

I don’t think this is so implausible. I wonder if we can defuse the harmfulness of things by changing our cultural expectations. It has certainly happened with homosexuality. People used to struggle with their attraction to their own sex, and feel intense guilt about their own inner self. Now they don’t have to. Those who abhor the action have shifted to loving the sinner but hating the sin, which is clearly a better way.

Above all, please think about bias in interpreting linear regression estimates, and do not naively take population samples as indicative of cause.

Thank you twitter user @soft_fox_lad for directing me to the speeding research. If you want to see my writing more often, please subscribe. Thank you.