What Makes a Cartel Succeed?

Contradictory theory meets terrible evidence

Let us suppose that there are two firms which each produce an identical and homogenous commodity. These are the only two firms in the world, and no other firms can enter. They cannot observe the quantities produced by the other firm, but they can observe the price in the futures market. The price falls – what does this mean? It is consistent both with demand slumping, and with one of the firms breaking the agreement.

What is striking is that these imply completely different things. If demand has fallen, then one should reduce output; if the other firm is breaking the agreement, then you need to increase output. How can they maintain their cartel with such imperfect monitoring?

The first paper to really tackle this is Green and Porter (1984), who lay out the conditions for collusion when production is imperfectly observed. They show that if firms commit to responding to any fall in price below a certain point with a return to quantity competition, then it is possible to maintain the cartel. No firm ever deviates from the joint-profit-maximizing rate of production, and everyone knows this, but they have to resort to competitive pricing in order to make everything work. It’s subgame perfect because each firm expects collusion to eventually return, so punishing is individually optimal at each point in time. Thus, you don’t need to know if the markets are pricing in the possibility of defection, because your strategy rules that out as a possibility. This would be extended rather formally by Abreu, Pearce, and Stachetti (1990) to show that this is the case in arbitrary games with N players.

What I find interesting is how the strategy contrasts with Rotemberg and Saloner (1986). The likelihood of collusion being successful is given by whether the profits from defecting are exceeded by the profits from maintaining the cartel. It naturally follows that if demand increases, the profits from defecting now also increases. Thus, cartels will tend to break down during booms. This is completely different from Green and Porter!

Both authors were able to find support for their theories in pointing at the empirical record. Rotemberg and Saloner can point to Bresnahan (1987), who studied the breakdown in tacit collusion in the auto industry during the boom year of 1955. Green and Porter could point to Igami and Sugaya (2017) and the breakdown of the Vitamin C cartel, although that paper was yet to come. Still it is concerning that theory points to equal and opposite ways for cartels to break.

There are two basic approaches I see to this. The first is to look at specific cases of collusion, and see when they broke down. The other is to study markups for the economy as a whole. Relatedly, we can get data on specific firms, which may not be collusive. The trouble is, the evidence on specific cases of collusion is extremely bad. So too is the evidence for markups in the macroeconomy, although not nearly as bad as is the case for studying specific instances of collusion. I thus cite these papers with reservations.

Rob Porter studied his theory in the context of the Joint Executive Committee. The JEC controlled freight from Chicago to the East before the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. The railroads who formed it in 1879 did not have the ability to dictate the decisions of each other, but they could coordinate to enter a price war when they believed cheating occurred. The good shipped was overwhelmingly grain for export to Europe, and thus homogenous. The firms took account of known cost-shifters in prescribing punishments, such as the cost of ocean shipping, and seasonal variation in prices due to lake steamers entering and exiting as the lakes iced over. Accordingly, when estimating prices and quantities, he has a dummy variable for whether the lakes are open to navigation.

The empirical portion builds off of Bresnahan (1982). Porter has an equation to estimate demand with a cross sectional regression. Supply is summed up from the individual supply functions, and then is multiplied by a variable between 0 and 1 representing, at each extreme, perfect competition and perfect collusion. This variable can change over time. I don’t entirely understand how he estimates it here, but he shows that prices were lower preceding periods of punishments, and that price wars as punishment did occur. However, he doesn’t find conclusive evidence for his theory – so much so that both Rotemberg and Saloner, and Porter, separately cite it as evidence for their views. Glenn Ellison (1994) explicitly considers the case of the Joint Executive Committee in light of both papers, and argues (tepidly) that it supports Green and Porter.

Levenstein and Suslow have a comprehensive survey in the Journal of Economic Literature in 2006, which I think really makes it clear why looking at particular cartels cannot be that helpful. Not all cartels are the same. Some of them might exist in name and not in factSimply studying one cartel is hard enough. You need to measure the markup, which is based off of data you cannot see and instead must infer. Each one requires careful study, which means that you will not get a random sample of cartels. Setting the sampling issue aside, the evidence is all over the place. Levenstein and Suslow find that demand instability in either direction undermines cartels, but business cycle fluctuations which are observed by everyone are not important.

If we’re willing to use only the cartels which got busted, Hellwig and Hueschelrath (2017) look at what predicts a firm exiting a cartel, using the universe of cartels which the European Commission broke up. Consistent with Rotemberg and Saloner, they find that firms were more likely to leave during periods of increased demand. Levenstein and Suslow (2011) study the determinants of cartel breakup, and arrive at the very boring answer that the main reason cartels end is antitrust action. No surprise, given that their sample is largely cartels which the competition authorities had heard about!

Meanwhile, in the macro literature there is a considerable literature on what happens to markups during times of booms and busts. Note that there are many reasons why markups might occur, and collusion is only a part of it. If you think that wages are sticky, for instance, then markups will be procyclical, increasing in booms and decreasing in busts. While only obliquely related, the markups can still shed some light.

As Nekarda and Ramey (2020) write, though, “There is no consensus, because estimating the cyclicality of the markup is one of the more challenging tasks in macroeconomics.” Nekarda and Ramey have an excellent discussion of the macro literature in section 2. Markups should be procyclical if Green and Porter are right, and they should be countercyclical or acyclical if Rotemberg and Saloner are right. (Unfortunately, Rotemberg and Saloner are perfectly consistent with markups being procyclical, just not by as much as they would otherwise be). The macro literature tends to find that markups are procyclical, but this should be taken cautiously for the reasons mentioned.

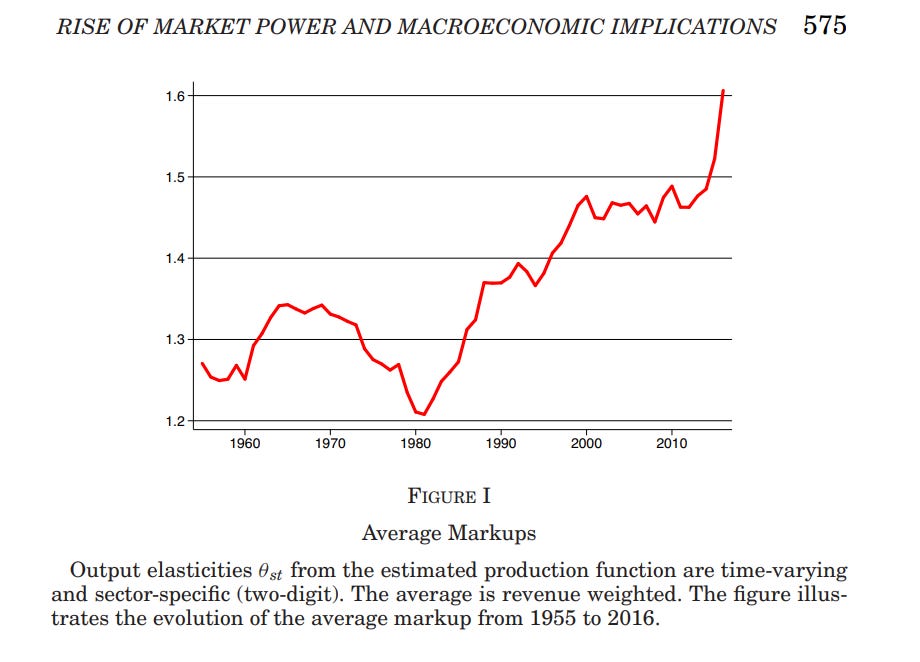

Last of all, there is a literature (typified by De Loecker-Eeckhout-Unger (2020)) which is an intermediate between the broader strokes macro work, and the house-by-house fighting of analyzing different cartels. They estimate a production function for each industry, and use it to find the markups. Below are their results.

I’m eyeballing it, but I don’t see business cycle fluctuations.

I’m not gonna lie to you, this wasn’t the article I thought I was going to write going in. Many times when I write an article, I start writing after understanding the theory, or perhaps reading a couple papers, and then fill in the rest later. The theory is clean and cool, but the empirical evidence is absolutely dreadful. Big questions are hard!