Harvey Leibenstein’s 1966 article on what he calls “X-inefficiency” is the forgotten forefather of an enormous literature on productivity. Why are there such big gaps in productivity between firms? Why do they persist so long, without inefficient firms being chased from the market? Why would managers leave simply enormous sums of money on the table? In this essay, I argue that productive inefficiency is real, and that it is largely the result of choices by managers. In a world lacking competition, managers are not pressured to find new ways of producing.

i. Leibenstein’s thesis

Leibenstein first looks at the distortions from allocative efficiency. Skillfully, he begins by stressing the superfluity of monopolistic distortions. Harberger famously estimated the distortions at 1/13th of 1 percent – other contemporaneous studies find similar estimates. The distortions from tariffs approach, at most, 1 percent. Moreover, monopolistic distortions could never, given plausible elasticities of demand (that is to say, the slope of the demand curve) produce very large losses anyway.

But the harms from monopoly may not lie in them being profit maximizing, and reducing the level of output to sell higher on the demand curve. Rather, it may lie in the inculcation of sloth and the tolerance of poor management which monopoly enables. Leibenstein thinks that firms systematically do not maximize profit when they don’t face much competition. This is a big claim, and I do not want us to take it too far. That firms may not profit maximize does not mean that neoclassical economics is all of a sudden worthless, or generates no knowledge. The world is kludgy. Information is expensive and non-divisible. Firms could produce things in a better way, if only they knew how. Competition empirically leads to greater productive efficiency, rather than merely greater allocative efficiency. How do we rationalize this commonsense observation in a rigorous way?

ii. Modeling it

I think the answer is to focus on the externalities of innovation, in the presence of non-linear utility from money. It is cheaper to copy, than to act in a new way. As someone who invests in finding new ways will get only a small part of the total benefits, it will naturally be underprovided relative to the social optimum. As profits fall from the introduction of competition who, importantly, have ideas which are different from the local consensus, it forces local producers to adopt new ideas or perish. This is basically Banerjee’s model of herd behavior – people receive a signal on the right way to do things, and mistake valueless herd-following for a real signal of the best way to do things. An outside push toward better management practices has the opportunity to improve welfare, because things will be stable with too little investment into innovation.

Second, we can assume that utility from income is non-linear. When firms are doing well enough, the marginal benefit of finding new practices that increase profits is less. People try to avoid risks, even at the cost of losing productive efficiency. When people are in danger of bankruptcy, things change – it becomes worthwhile to take on more risk in finding new production techniques. This approach has its antecedent in Hart’s 1983 paper “The Market Mechanism as Incentive Scheme”, where satisficing managers only do as much as they are forced to by competition. My take is stronger than Hart’s – where he focuses on agents for the owner, who collect some sort of gain for keeping their job in existence but not necessarily for producing more, I include firms which are entirely owner managed. Even though they collect the whole return to their efforts, the correlation of money and utility isn’t the same over all levels of income

iii. The empirical evidence

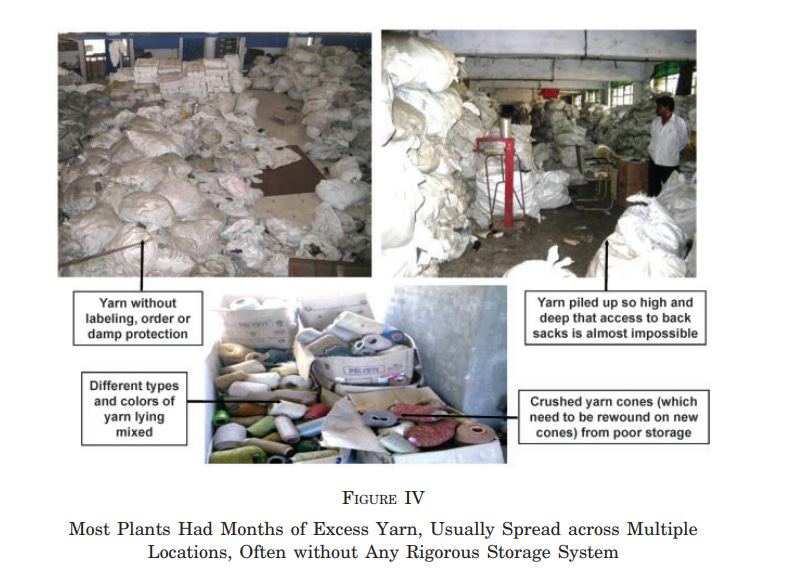

In his paper, Leibenstein shows that simple changes in firm management practices lead to enormous changes in production. He cites examples, but they are few in number, and this is something modern economics can lend more weight to. The best paper to read summing up the evidence on what determines productivity across firms is Chad Syverson’s “What Determines Productivity?” from 2011, which establishes the facts of the world in readable prose. Delving into specific papers, Bloom et al (2013) ran a randomized controlled trial (an RCT) on Indian textile firms, where some firms were randomly chosen to receive management training. The management advice was as simple as “record inventories”, yet this led to staggering increases in productivity – within the first year, treated firms saw a 17% increase in productivity, or a gain of $300,000 in productivity. This gap in productivity persisted, even nine years later on, in a follow-up study. This isn’t surprising, given that the factories looked like this:

In other quasi-experimental evidence, Giorcelli 2017, in chapter II of her dissertation, finds that exposure to American management practices had a large and positive effect on firm survival in post World War II Italy. (Additional coverage here). Foster, Haltiwanger, and Syverson (2008) document enormous differences in productivity between the most and least productive firms, even for homogenous goods facing seemingly competitive markets. Bloom and van Reenen 2007 collected survey data from 732 medium sized manufacturing firms in the US, UK, France, and Germany. They had a consulting firm independently (without knowledge of the firm’s financial status) evaluate the answers and grade their practices, and found that firms with better management practices were considerably more profitable than those without. In fact, much of the difference between American and European productivity is simply due to the adoption of IT by better managers. European firms face lower levels of competition, and are more likely to be passed down by direct primogeniture, both of which result in lower levels of output. America’s open, competitive markets mean that they are top to bottom better managed, and lack the characteristic long tail of badly run firms in developing countries and Europe. What I do find striking is that this advantage in management practices extends across national borders. American multinationals doing business overseas are better run than European multinationals in their own countries or abroad, even though they are obviously competing in the same market. (And in China, foreign-owned firms are more innovative than Chinese owned firms). This indicates spillovers in knowledge – competition in one of a company’s markets leads to them developing practices to survive in that market, and they can cheaply apply them elsewhere. This seems like quite strong evidence that it really is informational constraints which are responsible for poor firm productivity.

Firms seem able to make the most astonishing changes in production decisions in the face of competition. I covered Bridgeman 2011 in a prior blog post; in a world of lessened competition, the optimal way for unions to negotiate for rents is to insist on make-work jobs. (Why? Recall that the level of production is dependent on marginal cost. If unions raise wages, they raise the marginal cost of production. If they insist on a fixed number of jobs which add nothing to production, it becomes a fixed cost and does not impact the level of output, only whether or not the firm is in business. Clever, isn’t it?) Schmitz 2005 examines the productivity of iron ore miners in the Great Lakes before and after the entry of foreign competition from Brazil. For nearly a century, Minnesota mines faced no competition, save from themselves. As before, the unions’ optimal strategy was to insist on inefficient production technologies. In the initial crisis after competition came, output fell by 30% and 25% of the mines in Minnesota were shut down, but it soon rebounded to 92% of the pre-crisis level. Meanwhile, labor productivity rose 68%, and total factor productivity (TFP) rose 42%. They were perfectly capable of increasing profits by doing this earlier, but they chose not to. Now, it’s possible they were actually avoiding some fixed cost, and there is an optimal number of firms with poor management practices. I actually covered a not implausible model of the world a few days ago, which leads us to the conclusion that the adoption of good management practices actually leads to a loss in social welfare; nevertheless, good management practices are more broad than what they describe, and the inefficiencies from informational imperfections may, and almost certainly do, totally outweigh it.

I mention the last paper as a caution against naively thinking outsiders can do better. Firms might produce less than they are capable of because, as George Stigler, in a 1976 article on the subject, argued, Leibenstein is ignoring relevant constraints. Some productive techniques may not be worthwhile with different conditions. People face a trade-off between leisure and maximizing the production of a good, such that “factory discipline” isn’t worthwhile in some industries. Profit isn’t the be-all, end-all either. Managerial changes might be trading off against some unobserved aspect, like how hard the manager has to work or so on.

A specific example, coming from India. The efficiency of Indian labor has long been remarked on as particularly bad in the older economic history literature. (See, among others, chapter 16 of “The Development of Capitalistic Enterprise in India” by Daniel H. Buchanan, Greg Clark (1987), and Pseudoerasmus on labor repression in Japan as compared to India). Bhagwati and Desai’s “India: Planning for Industrialization” (1970), however, contrasts the ramshackle state of the textile industry with the Tata steel works at Jamshedpur works. (p. 53) There, Indian workers worked in conditions like that of the West, because delay and disorganization was especially costly. They were in competition with very efficient producers in Britain. There was nothing inherent to the worker, only the conditions which they faced. In contrast, as with many of the prior studies, the Indian textile firms were behind tariff walls. A lack of competition caused indolence, complacency, bad practices and stagnation.

The focus on information is what can reconcile these stories. Contra Stigler, information is not a good like any other. It cannot be divided. It cannot be appropriated, except through the kludgy legal action of a patent. It can scarcely be kept secret. It may benefit everyone, and yet never be found for want of coordination. Bloom, in the RCT on modern day Indian textile firms, asked managers why they hadn’t adopted the better management practices before. They apparently believed it wouldn’t improve profits! It is a lame excuse, but I think we can, to some degree, take them at their word. They didn’t have the imagination for it. Nobody was in danger of going out of business, so no one resorted to desperate measures and found it by accident.

iv. Imagination as fundamental constraint

I think there’s really something there to “imagination” as a constraint on human productivity. One doesn’t know what they don’t know. People are quite likely to work in the same field that their parents do, even in fields where it isn’t plausible that they have a leg up over others. It’s not mere nepotism. I saw a seminar presentation a few weeks ago, looking at the correlation of occupation between generations. People tend to do exactly the same jobs as their parents did, to an astonishing degree of specificity. In England, occupational status is quite persistent generation to generationThe best predictor of enlisting in the Army is having someone in your family who served before. My dad was an economist, but that’s not what I came to school to do in my freshman year, he having died when I was 12. I did end up becoming an economist, but I have no doubt that if he had lived, it would have been far more present in my imagination, and I could have started earlier.

More anecdotes, before the studies start anew. I have worked as a tutor, on the side. I asked a kid what she wanted to be when she grew up. She said a doctor — more specifically, an ophthalmologist. It’s a big word for her to know at her age. As it happened, her mom is an ophthalmologist. Most people wouldn’t register it as a thing you could just go out and do — our vision is blinkered. (Perhaps occluded?!) My boyfriend more or less tweeted his way into being a full-time software engineer by sophomore year of high school — I have no doubt there are lots of people out there able to do that, they simply have no idea that that is a possibility. Waiting till after college to do anything is normal. It’s what everyone does. Even in college admissions, poor kids are less likely to apply to selective colleges. This difference remains even after controlling for ability, and, as in the linked study, providing small changes in information availability led to large changes in application and attendance. Parents underrate the benefits of moving for their kids as well. There are a lot of studies showing that objectively terrible shocks – your house getting burned down by lava, having your public housing demolished, and so on – are actually beneficial to income, especially for kids. Chetty has a study out just now on neighborhood influences on future life success. It’s not even what your parents do, in this telling, it’s what other parents in your year and in your area do. Kids imitate what the adults are doing. I think adults also imitate what the adults are doing, and we’re all in little local maxima of ideas.

This fills me with a mixture of hope and despair. Hope, that better things are possible, without needing to rely upon new discoveries which may never come; despair, because it not having happened indicates that it may never. I would be less willing to assume that things are really as good as they can be, either in firm management or your personal life. Be willing to change more things. Be more ambitious. Take more chances. You can just go out and do things – all you need is the imagination.

I like reading almost anything about business in India. Please keep writing. Your voice is important

I lived near a train station and walked there each day to commute. After about 5 years, a neighbour told me my walk was wasteful. If I instead set off *in the wrong direction* I could go down a street that led to a street that went on an angle and so reduced total walking time. This was before google maps, and even though i could have checked it on a regular map, it never occurred to me that was possible. It saved about 40 seconds off a 10-minute walk, which makes a difference!

tl;dr you can get stuck doing things inefficiently for a very long time for want of imagination.

There's a lot to be said for varying your life a bit over time, doing things in stupid ways, trying odd ideas, just to open up the possibility space that you stumble on something good.