Why Do We Hate Inflation?

Psychological defect or rational response?

Why do people dislike inflation so much? Who dislikes inflation – and how viciously they dislike it – seems to defy any logical explanation. People believe that it erodes their standard of living, but they believe this whether or not it actually does. The vast majority of consumers today are debtors, who should benefit from unexpectedly higher inflation through the real cost of their mortgage and other obligations falling. We have seen debtors call for high inflation in the past – the free silver movement was explicitly a call to inflate away the debt of farmers. Yet, we find people have an intensely negative view of inflation – as Binetti, Nuzzi, and Stantcheva write, “inflation is perceived as an unambiguously negative phenomenon without any potential positive economic correlates”.

I want to offer some stories of why we dislike inflation so. They are: heterogenous inflation experiences; lumpy rises in income keeping pace with price changes; and some simple psychological failing of humans. I believe there is some support for each of these stories.

First, people’s experience of inflation is incredibly heterogenous. If inflation is ticking along at 2% pace, this means that there are some people whose personal bundle of goods they consume increased at a rate much higher than 2%, balanced out by some people’s bundle actually falling in price. If we presume that inflation experiences are normally distributed, then an increase in the average rate of inflation leads to a non-linear increase in the number of people whose bundle changed at a rate above some threshold. Thus, we can explain why people are so much more upset by a 4% rise in inflation than a 2% rise.

This ties in with the second story. While inflation leads to a rise in labor income, which may very well balance out inflation in the aggregate, people will be worse off if this is achieved through infrequent but larger changes in income. When inflation increases, more people will be in the unlucky bunch whose prices go up a lot, and whose wages have not gone up at all. People make consumption commitments ala Chetty and Szeidl (2007), so even small rises in their cost of living are sufficient to cause very large changes in utility.

Third, maybe people are just kinda dumb about this. They see prices go up, and prices going up are bad. Sure, their income might also be rising, but they don’t attribute this to inflation – it’s due to them being an especially good and hardworking employee. What people want is not a fall in the rate of inflation, but rather a return to the lower price level of the past. As a complementary part of the story, since much of the reduction in inflation is due to the introduction of new goods, we will only ever observe prices go up. If it is harder for us to think about what the shadow price of new goods are, then we will get a distorted view of the world. The primary determinant of beliefs about what inflation is are, in fact, the prices people pay at the grocery store – recent work by D’Acunto, Malmendier, Ospina, and Weber (2020) shows that people are influenced much more by what they pay than what they hear on the news, and that these observed price changes tend to be higher than the reported rate of inflation.

Fourth, maybe changing prices makes planning more complicated. People get used to things being such and such a price, and when this changes, it disrupts our ability to plan for the future. I believe that this is real, and an inconvenience, but not nearly as important as other causes.

The classic starting point is simply asking people why they dislike inflation. Binetti, Nuzzi, and Stantcheva (2024) is one such study, as is Stantcheva (2024); Shiller (1997) is, to my knowledge, the original. People are adamant that inflation reduces their real buying power. When asked why and how, there is a confused mess of reasons. In Stancheva (2024), only half of respondents could even give a relatively correct response to the question “what is inflation?”. In that survey, less than ten percent of respondents attributed inflation to monetary policy, with people largely focusing on “greed” and “the Biden administration” (depending on whether they are a Democrat or a Republican”. They do not believe that there might be tradeoffs between inflation and unemployment, and indeed are often concerned not just with the rate of change of the price level, but the level itself. Shiller (1997) reproduces substantial portions of a Reader’s Digest article in which (in 1995, mind you) the author reminisces about things used to cost less, when he was a boy, and that this “good economy was inflated away”. This despite his pay being much lower too. People tend to think that increasing interest rates will increase inflation, and vice versa. And so on – you will not get a coherent policy out of the beliefs of the voters.

People are quite explicit about their beliefs regarding wages – inflation is something done to them by others, often for malign reasons, while wage changes are something they do for themselves. We can put this view in the best light possible, though, and consider if wage changes are uneven.

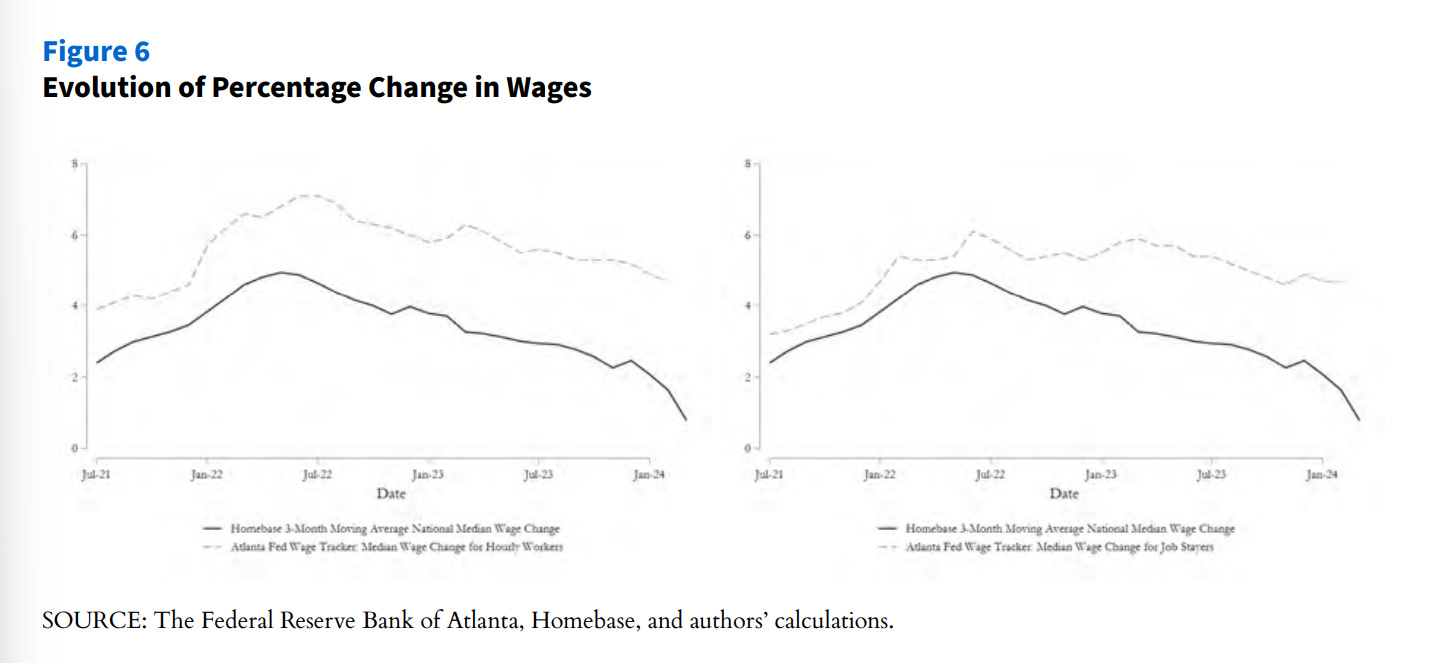

The story of wage changes not consistently and smoothly keeping up with wages has a simple test. If the size of wage changes increases during inflation, then the rate of wage changing has not kept up with inflation. We don’t have to do much work here – Dvorkin and Marks (2024) conclusively answer this in Figure 6.

This notably contrasts with price changes for consumer goods. Nakamura, Steinsson, Sun, and Villar (2018) do not find that the absolute size of price changes increased during times of higher inflation. Goods prices go up smoothly, and wages do not. Some people exceed inflation; others do not. In the Biden administration, if you consider average wage gains, they kept up with inflation; if you consider the median person, they saw no change.

This supports the story where people attribute inflation to the world, and wage changes to themselves. They did, in fact, largely earn increases in wages! Across the board wage changes to keep up with inflation aren’t that common, it’s just that merit wage changes are a bit larger than they would otherwise be. Further, people’s personal changes in their consumption basket are also extremely heterogenous. Kaplan and Schulhofer-Wohl (2016) show that, even in relatively low-inflation times, the interquartile range of inflation experiences by household is somewhere between 6 and 9 percentage points. Roughly speaking, with 2% inflation the 25th percentile household had their basket fall by 6%, and the 75th percentile household had theirs increase by 10%. I believe that utility with respect to wealth is curved, so these wide mismatches between wages received and prices paid must reduce average utility.

So far I have not seen any work on whether the dispersion of inflation experiences might have changed over time. I think it is a clear topic for research, and could be extracted with a month of careful work with Nielsen data.

I went into this article uncertain of what I believe. I now think I have solid answers. Wages are different from the prices of conventional goods. They change less frequently. It is this, with a healthy dose of psychological bias, that leads to inflation being seen as harmful. Returning to the question of debt raised in the first paragraph, while most people today are in debt to someone, they are also in the position of creditors with regard to their employment. This turns out to be much more important.

What do you think of the recent "menu cost" hypothesis that one contributor for disliking inflation is that people have to negotiate wage increases and they don't like doing that?

I would say it depends on the type, size and circumstances, so it can be a mix of both.

Also it is a Vector and does not affect everybody the same, not all people spend money on same thing and not all thing change the same % in value.

Sure people are bias and hate rising prices, while do not mind their loan rate staying relatively the same.

However there are several objectively negative side effects, that are especially visible with higher inflation.

-First is that inflation act as tax on money, and as such it is regressive since top 10 or 20% owns less cash and more assets that are inflation proof. And the higher it gets the more regressive effects are, even more so if there is not in place adequate and effective progressive taxation with no loopholes, but currently tax codes in many countries are far from optimal ideal.

-Secondly salaries for most people do not rise up automatically, they often lag for entire year and in many cases do not go up enough, plus people are forced to ask for rise even thought it is not rise in real terms, just nominal adjusting (purchasing power stays the same after full rise).

-Thirdly rich can take more credit to buy more assets then poor since they can more easily take larger sums with their wealth as collateral and because of that have also lower interest rates, hence they again benefit more with using it.

My opinion is that even though there is some subjectivity to it, it is objectively still net negative as it increases the wealth gap that is making society more divided.