Why Gravity?

Intuitive explanations of the theory of trade

I’m pretty sure everyone has heard of gravity. Objects are attracted to bigger objects, and ones which are closer to them. Economists use gravity too. When countries engage in trade, they trade more with countries which are closer to them, and with the countries which are bigger. This is such a solidly established regularity, in fact, that we can use this to estimate our models. But, for the longest time, I lacked an intuitive understanding for why this would be the case. Now that I have it, I want you to have it too. In doing so, I am building off of “Putting Ricardo to Work” by Eaton and Kortum (2012).

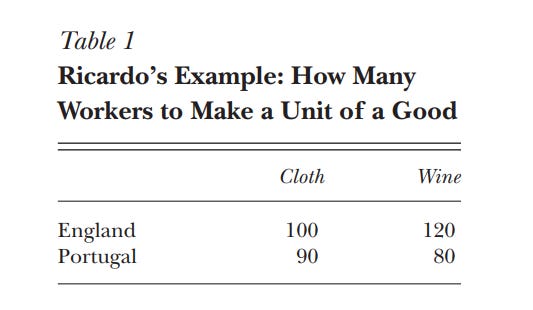

One reason why trade occurs is that different places have a comparative advantage in producing some goods over others. David Ricardo’s famous example, which is still used by every intro micro teacher to this day, has two goods, and two countries. Portugal and England are both capable of making cloth and wine, but they require different amounts of labor to make a unit of a good. Portugal is superior to England in producing both cloth and wine, but if trade is costless, they would be better served producing just wine, and trading for cloth. They have an absolute advantage – they are better in both – but they have a comparative advantage in wine.

Now, we need to be specific about tastes and preferences. Ricardo is assuming that the two goods exchange at a price of one, but we need to be specific about why they’re trading. We could say that they have Cobb-Douglas preferences, and prefer an equal amount of each. The moment we say this, though, it is possible for the price to change as a function of the labor supply in each country. We need to say something about the wages paid in each country.

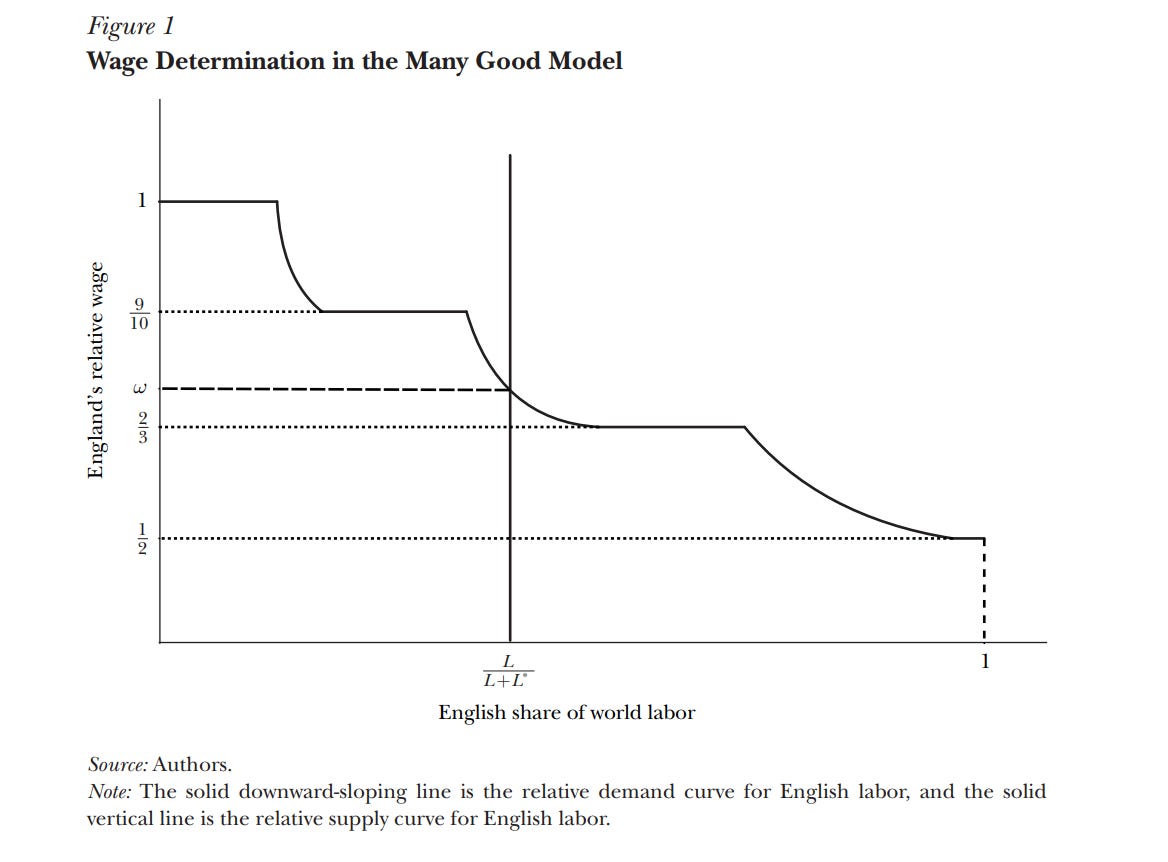

Take the example above. Denote the English wage W. The cost of making cloth or wine in England is thus the labor requirement times W. If the wage is too high, then nothing will be produced in England. If it is too low, then nothing will be produced in Portugal, because both goods will be produced in England. Now we can solve for wages as a function of their absolute advantage, with England always being lower.

When we add in an additional good – linen, say – something interesting happens. The number of goods produced becomes a function of their wage, with the number of goods increasing as wages fall, and the wage determined by their share of the world labor supply. Let’s say that producing a unit of linen takes 100 workers in both England and Portugal. If you plot out what happens, this is what it looks like.

What’s going on? Above a wage of 1, then Portugal will make everything. As England becomes a bigger share of the population, they would start producing more linen than people prefer. Their wages falls, and they start producing cloth as well as linen. As their share increases still further, the wage must fall, and they must produce more varieties of goods.

Thus, we can explain why countries trade with bigger ones. That they trade with closer ones is, of course, much more intuitive to understand. If a country is further away, it is more expensive to trade with it. If you have the difference in trade costs as a function of difference, and you have the sizes, you can then predict how much trade should be flowing between countries. What trade costs will do is reduce specialization. If trade costs were infinite, then all countries would (approximately speaking) produce all goods; if they were zero, then we will have the optimal sharing of production. If it’s in between, it’s in between.

An extremely useful trick when dealing with lots and lots of goods is to just ignore them, pretty much. We say that there is a continuum of goods. Now instead of a staircase, we can just draw a smooth line.

Now this is just like a supply and demand curve! An increase in productivity will increase the varieties that country exports, and wages will rise in that country. Additionally, wages will rise in Portugal but the variety of goods will fall. Since we have trade costs between countries, but not within, we can also say that a higher population leads to higher consumption, and that a higher population leads to more varieties produced. (This is the famous home market effect of Krugman (1980).)

Eaton and Kortum (2002) generalize this to arbitrary goods and arbitrary countries. The trick in that paper is to not take a stand on the absolute or comparative advantage of any particular industry. Instead, each industry draws its productivity from some distribution. The height of that distribution is the absolute advantage of that country, and determines the wage. The width of that distribution determines how heterogeneous the country’s productivity is. If every industry had exactly the same costs, then the country would produce all goods domestically and not trade at all. The gravity equation I just described above is what allows us to actually estimate that model.

How about empirical testing? Probably the best test of this all is Redding and Sturm (2008). They are looking at cities in Germany, rather than countries, but the same best framework can be used. When Germany was divided, the cities closest to the border saw a much larger increase in trade costs than the cities which were further away. This is not well explained by anything else, and the paper supports the theory at every turn.

Why have I been thinking about this? I am interested in why poverty has fallen. I would like to “pull out” specific causes, and see how much of growth can be explained. In particular, I would like to see if poor countries have gotten better at producing stuff, or if they have been stagnant, and instead the countries which they trade with have gotten better. This simple theory allows us to pull these apart. Both explanations for falling poverty imply increasing exports (because we will impose a balanced trade restriction), but the former implies increasing variety, while the latter implies decreasing variety.

I have not formally proven this. That is, unfortunately, not my strength. (Sometimes I feel as though I were born to be a lawyer, but I was cursed to recognize that lawyers are essentially useless). I welcome your comments.

I enjoyed the article. You are adept at presenting complex concepts in a manner I find helpful. Thank you.

For the last sentence of the penultimate paragraph, is it increasing / decreasing? So general idea you are positing is that as poor countries become more productive, there are more goods that they can produce relative to trade costs that are competitive on the world markets, so we should see the diversity of exports increase?

I'm confused for your initial explanation of introducing a wage into in England / Portugal model. If one country makes all the goods, how does the other country consume anything? Do they get endowments outside of wages in that model?

Also an even more basic question, but what exactly does the gravity model reveal? Is it saying that big countries trade more than would be expected given their proportional share of world population? Like if you ignored trade costs + assumed identical productivity across countries and said every country will trade a fixed amount of exports + imports per capita, then big countries will trade more, but that doesn't seem especially interesting. China and the US both have quite low trade shares relative to GDP right? I should probably just read the papers.