Witches

Why did we hunt them?

There is hardly a group more mistreated than witches. For nothing more than the crime of cavorting with the devil, riding broomsticks, and keeping toads as companions, women were burned to death in the thousands in Europe. Even today, hundreds of witches are killed in Africa every year. Why does it happen? Why does it stop?

The first thing to know about witchcraft in Europe was that it was not supported by the organized church at all. Our popular conception amalgamates it with the Inquisition, but belief in witchcraft was primarily a folk belief, resisted by the hierarchy. Witches were not officially believed to be capable of anything which humans couldn’t do, and most witchcraft accusations were more accusations of heresy than of the supernatural. Agobard, Archbishop of Leon, wrote in the 900s “Against the foolish opinion of the masses about hail and thunder”, and in 1258, Pope Alexander IV authored a canon stating that alleged cases of witchcraft would not be investigated by the church.

By the late 1400s, however, this elite consensus had broken down. Pope Innocent VIII wrote a papal bull at the behest of Heinrich Kramer, author of the Malleus Maleficarum, in 1484 recognizing the existence of witches, and the necessity for putting them down.

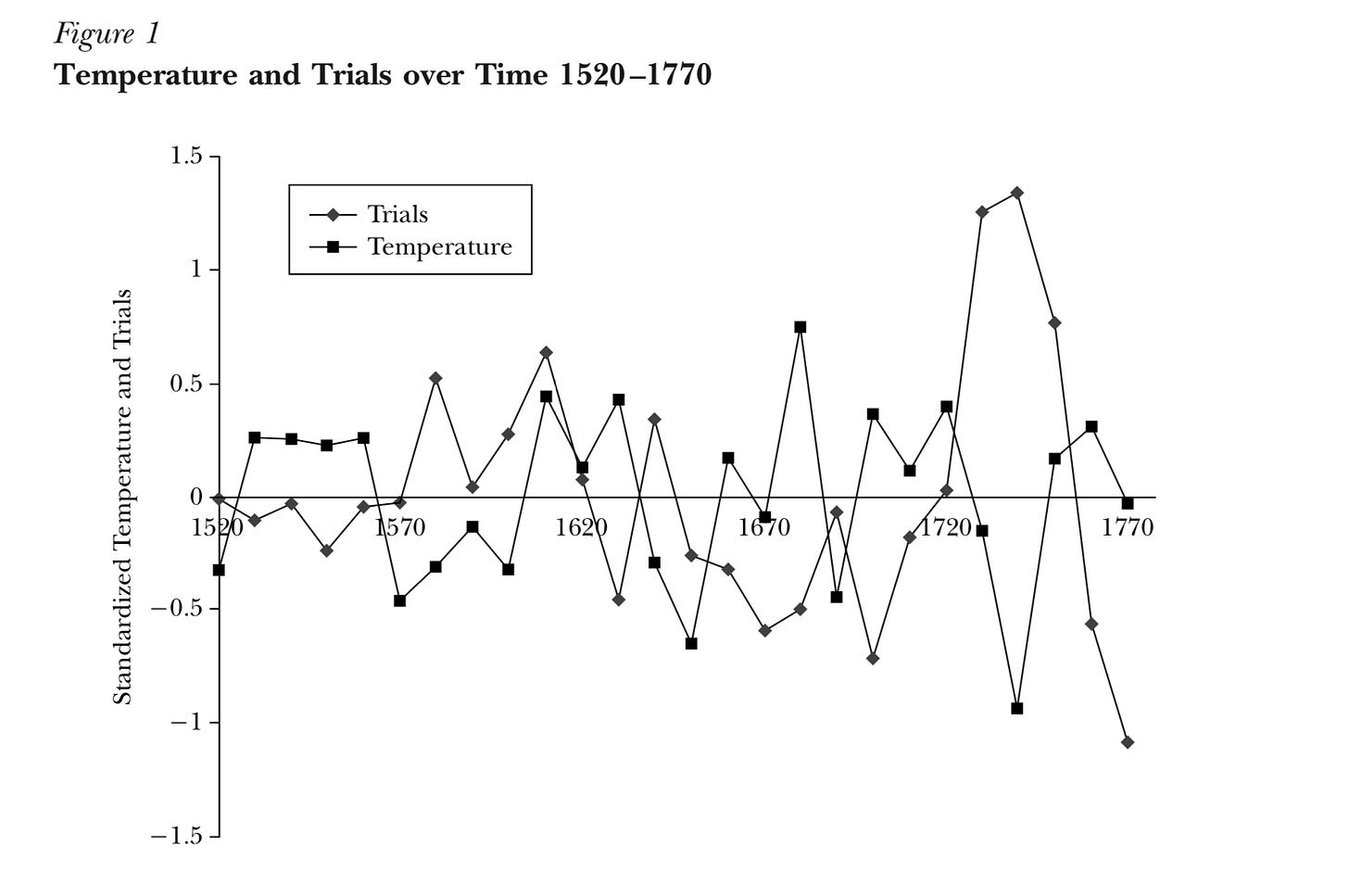

Some theorize that it was the weather primarily responsible. Oster (2004) points out the climatic backdrop. The Little Ice Age began in the 1300s, and we would not return to warmer times until the late 1700s. Resurgences in witch trials were associated with negative temperature shocks, such as those from a volcanic eruption. Witch trials returned around 1560, when a relatively warm lull ended

.

Look the close association of lower temperatures and more witch trials — it practically jumps off the screen!

It is striking how much of the folk belief in witchcraft was specifically about their control of the weather. As Agobard wrote, “In these regions, nearly all men, noble and common, city and country dwellers, old and young, believe that hail and thunder can be produced by human will. For as soon as they hear thunder and see lightning, they say ‘a gale has been raised’. When they are asked how the gale is raised, they answer (some of them ashamedly, with their consciences biting a little, but others confidently, in a manner customary to the ignorant) that the gale has been raised by the incantations of men called ‘storm-makers’, and it is called a ‘raised gale’.”

Witchcraft in the present day is also influenced by weather. Miguel (2003) uses rainfall shocks, and finds that persecutions for witchcraft in Africa sharply increase with extreme rainfall events (either flood or drought). This brings up an interesting question – when is rainfall an appropriate instrumental variable?

For starters, we should define our terms. An instrumental variable is some sudden change which is plausibly unrelated to the things in our model. When things are unrelated, this is called exogeneity. When things are correlated with each other, this is called endogeneity. The instrumental variable changes is something that affects X without being correlated with Y.

The trouble with rainfall is that it has been found to be correlated with way, way more than you would expect. It need not be the case that it actually cause rainfall (although in some cases, it does — rainfall in a season is extremely inappropriate for an agricultural study, because agricultural actually has a substantial effect on the local climate), but just that the things which correlate with rainfall also correlate with your variables of interest.

The rule of thumb is that, in the long run, everything is endogenous. As people have less time to adapt, the shock is more likely to be exogenous. I can believe rainfall IVs when they are one specific shock, but not when it is a long period of shocks. Here’s an analogy — war is caused by many things, but whether a bomb landed on your side of the street or on the other side of the street is plausibly random. So, I believe Miguel here. He’s interested in the short run effects, not the long run.

Oster and Miguel are not the only takes on witchcraft. Leeson and Russ (2018) offer an alternative story of witchcraft persecution in Europe. Rather than simply being about weather shocks, it was a way of appealing to the base prejudices of the people. Belief in witchcraft was widespread, and so religious entrepreneurs could offer a version of Christianity which allows for burning witches. When the authority of the Catholic Church was challenged, they were more willing to give the people what they want, and so both Protestants and Catholics alike burnt witches.

The evidence for this reading is twofold. First, it is striking how, at the country level, the areas where the authority of the Church was unchallenged saw very few witch hunts. Spain and Portugal and Italy, which saw no serious challenges to the church, were spared mob trials. Second, within the northern European region where most witch hunts occurred, places with more battles saw more witch hunts. Given that most of the wars of the time were religiously inspired, it is a reasonable inference to think that this is why.

This is not an airtight case, of course. Perhaps the battles caused the witch hunts directly, or the battles caused poor economic conditions which then caused witch hunts, in line with the Oster story. The stories are somewhat compatible with each other — religious contestation could be a necessary, but not sufficient condition, for the massive witch hunts of Europe. The smaller scale witch hunts of Africa and India are clearly related to negative shocks, and I don’t think we should think people in the past were extraordinarily different from today.

My dad knew relatives who were late holdouts on having purely rainfed crops.

Every single time they visited, any lul in the small talk meant one of them would worry aloud about the rain. Whether it wasn’t coming fast enough, or if it was raining they’d worry that ‘if it kept raining it would ruin the crops’

You could tell the anxiety just ate at them. And if they didn’t have heaters, and lost kids in the winter, maybe it would be the same way about the cold….

So maybe witches == bad weather is not surprising. It’s what the medieval peasants probably fretted about 24/7