You Actually Have to Read the Studies, You Know

Misrepresentations by a respected professor

Note: I began work on this article before I discovered something that Prof. Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at UCSD, seriously misrepresented the findings of a study in a recent New York Times opinion piece. However, I am averse to rewriting everything, and will be publishing as is.

I have begun work as a research assistant (part-time) for Prof. Alex Imas at UChicago. We are working on research on the effect of social media, smartphones, and AI, so as a consequence I am reading a lot of psychology studies which I would not otherwise read. Prompted by this, I want to attack an argumentative trope I see all the time from people who are not experts in a field: “there are numerous peer-reviewed studies which show X”. There are indeed numerous peer-reviewed studies which purport to show X. There are plausibly many studies which also show not X. Even if there are not studies which show not X, it is possible for those studies which are peer reviewed to not show X at all, and strictly speaking not even try to.

Take this concerned parent writing in the Washingtonian. Her son, who was a 9th grader at the time of the story, was constantly watching videos and playing games on the school issued laptop. She believed that this was negatively impacting his performance in school. I happen to believe her. I think she’s absolutely right in what she’s arguing for. I do not intend to belittle her in this article, just to point out that her argumentative style would leave her unable to discern truth from falsehood.

She (twice) says that there is overwhelming paper reviewed evidence that phones and laptops are a problem. What studies are these? It’s not entirely clear – she does not link to them, or even discuss them in a way that makes it clear which they are. She just mentions the results, as if being peer-reviewed means that any results they find are good, and equally so. With the aid of LLMs, though, tracking these citations down is greatly simplified. Take this passage:

>The number-one issue is distraction. On a laptop, it’s frictionless to open a new tab and surf. One study found that college students with laptops were off-task 42 percent of the time. Another found 28 percent of in-class laptop time devoted to nonacademic pursuits.<

The 42% figure comes from Kraushaar and Novak (2010). The 28% figure comes from Day, Fenn, and Ravizza (2021). (The latter the LLM couldn’t find – I simply had a hunch, and found that figure in the paper). These studies are very similar to each other, so I’ll focus on the later and better one.

Before explaining what is wrong with them, though, I should show what good studies look like. The best of them, to my mind, are Barwick, Chen, Fu, and Li (2025) and Abrahamsson (2024). These represent two paths to studying the effects. The first is to use individual level variation, as in Barwick et al, while the other is to use variation in the rules by school or location.

Barwick, Chen, Fu, and Li have data on three cohorts of students from a Chinese university in southern China, with 7,479 students in total. (They anonymize the name of the University in the text, but then thank the Jinan University IRB for approving it. Figuring out the name does not require much detective work). The university randomly assigns roommates and keeps those pairings throughout the university, which allows them to tease apart the effect of peers. They have grades, major, place of origin, and their eventual employment with the initial wages. They can then link the students to phone use records, which includes the locations of the students every five minutes.

They do not randomly assign phone usage to students. It is possible for the amount you use your phone to be correlated with your ability, which would bias our estimate of phone use’s effect. Instead, they use what are called instrumental variables to find the true effect. These are things which affect phone usage, and thus affect real outcomes, *only* through the channel of affecting phone usage. They have two.

The first one was China’s restriction of gaming time for minors, beginning in 2019. Some of the people in the sample were below the age of 18, and thus directly affected. Other people had friends who were below the age of 18, and thus the appeal of gaming online was affected. If we assume that there is no sudden break at age 18 in people’s academic ability, and that people’s friend group was not built around a future gaming ban for minors, then we have found the underlying causal effect.

The other is what is called a shift-share instrument. On September 28th, 2020, the game “Yuanshen” (you might know it under the name Genshin Impact) was released. It was the most popular game in China, and people spent a lot of time playing it. The assumption is that Genshin Impact increased the gaming time of people who were already frequently gaming by more than it affected those who didn’t use it.

With these instruments in hand, they can show that gaming reduces one’s GPA and earnings, and that it comes through the channel of spending more time gaming and less time studying.

Sara Abrahamsen (2024) does not have individual variation in usage, but she does have school level variation. It is a standard diff-in-diff study, where we compare places that banned phones at different times to similar schools which did not. We aren’t interested in the absolute level of test scores, but rather how they differed after the phone compared to those which didn’t.

Figlio and Ozek (2025) is also a good study, though they have less rich data on the participants’ outcomes. Rather than have many events, as particular schools ban phones, they have one big event when Florida bans cell phones statewide. Their object of interest, then, is to compare schools in one county whose students used phones a lot with those whose students didn’t use them all that much. They found more disciplinary incidents, especially among Black students, in the first year, but test score improvements in the second year. I’m not entirely sure I believe the mechanism – unexcused absences went down, and it seems to me that making school less pleasant should increase unexcused absences, not decrease them, which raises the suspicion that higher phone use schools had a concurrent crackdown on unexcused absences – and the study is incomplete as stands.

By contrast, a study such as Day, Fenn, and Ravizza (2021) is something which might seem promising, and will be consistently cited in support of this thesis, as Jean Twenge did in the New York Times this Sunday, but does not in fact show anything at all. They recruit participants from an intro psychology class to install an app which monitors their computer use, and then categorize their use during the lecture into course-related/not-course-related stuff. Controlling for intelligence as proxied by ACTs is a good step, but it isn’t sufficient. It could be that the people who are checked out mentally, and aren’t looking at the material, were going to be checked out mentally with or without the laptop.

I would also like to point out that the central regression is supremely unimpressive.

The next bloc of studies cited is this:

>A study of middle-schoolers, for example, found that reading on a laptop resulted in poorer comprehension than reading on paper. (In ninth grade, my son had multiple virtual textbooks, and his English class assigned PDFs of novels.) Additionally, a 2014 study suggests that note-taking is less effective on a laptop than by hand.<

There are actually two different studies which could plausibly the first one, Goodwin, Cho, Reynolds, Brady, and Salas (2020) and Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick (2012). The second is obviously Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014), so I’ll respond to that one. The study is, in fact, good, insofar as it is trying to answer a question in a way which actually answers it. It is not at all clear if the question they are asking maps onto any relevant thing – they’re having people watch Ted talks and answer a quiz, this is hardly a class, nor will we know if things differ for meaningful skills – but, they do have random assignment of treatment.

What she fails to mention is that there is a now considerable literature replicating this, and the facts are much muddier. Many find no difference in comprehension at all. Morehead, Dunlosky, and Rawson (2019) find that there is nothing magical about longhand note taking versus laptops. Urry et al (2021) (I normally try to credit all authors, but I think she credits all 74 undergraduate students who participated as authors) also directly replicates it, and finds no effect.

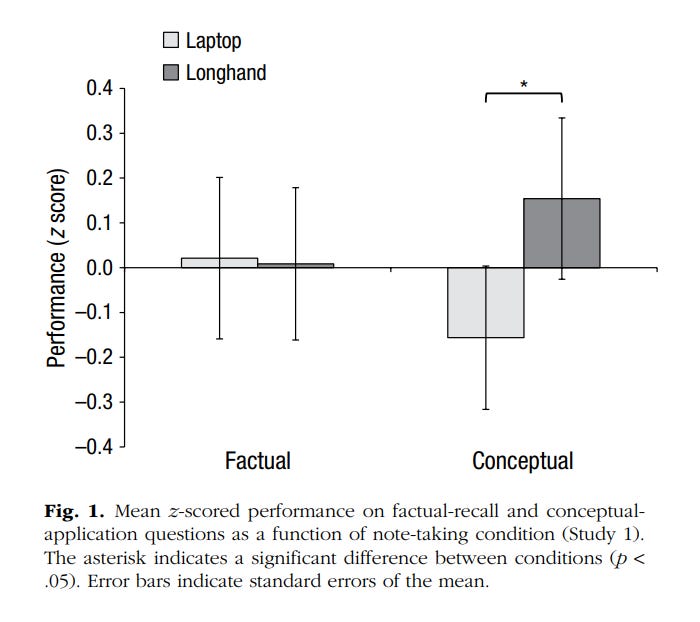

This would be readily anticipable if one had actually read the study in question. Their central test is below. There is obviously no difference whatsoever in factual recall. The conceptual recall is significant at the 90th percentile, and does not take account of us testing multiple hypotheses. So what if they take more notes! Comprehension is the object that mattered, and they could not show an effect.

She turns next to heterogeneity in outcomes.

>But laptops seem to hurt the worst-performing students most—particularly boys, whose impulse control tends to lag girls’. A 2016 study found that “permitting computers is more detrimental to male students than female students” and that stronger students saw fewer adverse effects from screens. Another study arrived at a similar result, concluding that “the negative effect of computer use is strongest among male students and driven by weaker students as identified by their cumulative GPA.”<

I cannot identify what these studies are. I believe they are based on Patterson and Patterson (2017) and Carter, Greenberg, and Walker (2017), who both had working papers come out in 2016. However, I cannot find these quotes in the study. They are in contradiction to Abrahamsen, who finds larger results among girls. In short, we don’t actually know if there is tendency for male or female students to be more affected, and I think it is not implausible that the military academy at West Point is a systematically different environment than Norwegian schools.

>A 2016 study, for example, found that when some UK high schools banned phones, the positive effects were “concentrated in the lowest-achieving students.”<

This is surely Beland and Murphy (2016). Finally, a good study.

Simply summing up studies, without caring for their quality, is bad. There is so much that can sneak in. I read through some of the studies which Barwick et al cite, and one of them (Greitemeyer (2019)) is a sorry example of the sort of garbage which gets published by psychologists. We want to know if violent video games cause crime. His method is to ask people how much time they spend playing violent video games, and ask them how aggressive they feel toward other people. He then surveys them again, and controls for the amount played the first time around. Nevermind that you have no plausible reason to think the causality runs from playing violent video games to feeling aggressive (whatever that really means) toward others. But in it goes, into the pile of papers which are cited without reading or any consideration of their methods.

We can forgive a journalist and a concerned mother. She is almost certainly right in her belief that allowing her adopted son the unfettered ability to watch TV in class instead of learning is bad for him. The studies were cited as dressing to a story already decided, and weren’t even really supposed to be checked. But can we forgive this sloppiness in Jean Twenge, who is a professor of psychology at SDSU? She is an academic. She should surely be responsible in what she cites, and have a discerning eye for the evidence. Let’s look at her recent op-ed in the NYTimes.

She starts off fine by noting the big picture trends. Test scores have been sliding, partly as a result of Covid, but the trend started far earlier. I want to emphasize that I am absolutely not against this, and I think this is actually a very good argument! Well-identified studies are not always possible, nor can we expect them to say anything about general equilibrium without assumptions. Noting the fall in test scores, the concurrent rise in electronic usage, and the obvious causal mechanism is a really important argument to make, and one that I am inclined to believe. “No evidence”, in the sense of studies showing that, need not always mean that there is really “no evidence”.

Prof. Twenge then detours slightly by mentioning pornography, which is pandering to prudes. Exposure to pornography is infrequent, although wrestling that out of the writeup by CommonSenseMedia is much harder than it should be, as they don’t report the full information on this. Instead, they frame frequent as “several times a month”, in a way that indicates that they don’t have anything which might allow them to say that any significant fraction see it at least once per day. She is demagoguing here, but in a way not out of line with normal NYTimes opinion piece writing.

She gets back onto stronger grounds by noting that it does indeed consume a lot of time, but what do you know? She cites Day, Fenn, and Ravizza (2021). We have been over this. It does not tell us anything about the causal effect of non-school use of laptops during class. She then cites a UNESCO report, which is cop-out, as it is 526 pages long and highly unlikely to bring forth new evidence.

She next cites her own work, which has a reasonable approach. She’s essentially doing a difference-in-differences study, where the change in test scores over time is regressed on the change in phone usage, except this time it’s comparing countries. This is fine and reasonable, but you should not interpret this as proof. In the difference-in-difference studies covered earlier, the argument is that the timing of the changes in the legality of phones is uncorrelated with the differences in trends in both phone usage and grades across school districts, which is plausible. Here, we have to argue that there is no possibility of a common factor causing both phone usage and grades. They also only have 36 countries. I have not read the study, because I cannot access it now. I do know how these sorts of things are written. (As an aside, I’d like more attention paid to demographic shifts in explaining changes in test scores over time.)

We return to the safer waters of reasoning without citing studies, but then she immediately runs aground by uncritically citing the research showing that paper reading is better than digital reading.

When it comes to claiming that people who take notes on paper, as opposed to typing, get better grades, she makes an absolutely massive error. The effect on course grades in the study she cites is a hypothetical exercise. They are taking studies where someone is shown a 20 minute Tedtalk and then asked quiz questions, assuming that grades are normally distributed and that there is no heterogeneity in effects by person, and showing what would happen if the note taking shifted your total ability.

I genuinely want to scream about this. It is not what the study shows at all. If you can’t tell, I did not expect this going in, and am now stunned. I cannot go on. I will be writing a letter to the editor.

Jean Twenge also wrote an entire book that, as far as I can tell from online reviews, decides to attribute a bunch of societal shifts to generations, which are basically randomly chosen 20-year-or-so periods. This seems like it obviously has to be bogus pop psychology? People don't suddenly become a new person because the year is different- all these variables should be changing continuously. I haven't actually read the book but now I am tempted to because it so predictably seems bad and maybe it would be fun to rip it apart?

So yeah, based on this evidence I feel pretty confident saying that Twenge has low scholarly standards.

Timely reminder to take ALL studies with a grain of salt. There are always more perspectives that could be relevant but even provided citations are selected to support the opinion being argued.