Norway has one of the lowest crime rates in the world. It also has some of the nicest prisons in the world, with an emphasis on education, job-training and rehabilitation, and when people are released, they go on to reoffend at a very low rate. By contrast, the United States has harsh prisons, high crime, and high recidivism rates. Might these be related?

Perhaps. You have an explanatory problem to overcome. That places with low crime rates should have low recidivism rates is trivial. Imagine every person commits crime randomly, at some rate unique to them. Further suppose that a place with high crime is one where people have higher rates on average, and low crime means lower rates on average. Everybody in jail (to a first approximation) has done a crime, but if their rate was lower before, their rate after will still be lower. We can’t assume that it’s Norway’s focus on rehabilitation which causes lower recidivism rates, when we would expect their recidivism rate to be lower given nothing else!

And so Norway’s prisons are obvious — they are nicer because they can be nicer. Comfort and security trade-off against each other in a prison environment, and with less dangerous prisoners, you can afford more comfort and privacy. If Norway’s criminals had a higher propensity to do violence, then we would surely find the advantages melt away, as prisons focus more on securing their prisoners.

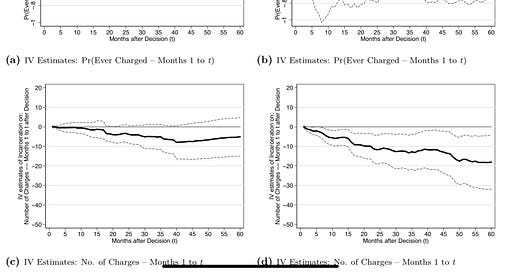

The best causal evidence on the effects of incarceration uses what are called “judge IVs” — some judges are nicer than other judges, and give shorter sentences or probation instead of jail terms. If the judges are randomly assigned, then you have exogeneity; sentencing unconnected to the facts of the case. There are some limitations — first, it is surprisingly easy for the “exclusion restriction” (in essence, that judge assignment really is random) to become undone. Second, we can only see the effects of prison strongly for the marginal defendant, who is on the edge of probation or jail time. In more serious cases, sentencing may be out of the hands of the judge, or the effects of additional years of prison are much more muted than the gap between prison and no prison. With this in mind, there is a study on the effects of prison in Norway. It finds that it reduces recidivism among those who were unemployed at the time they were arrested, although not among those who were employed. We should be modestly skeptical of the paper, however, because it checked multiple possible outcomes, and that was the only one which was significant. As you check more and more outcomes, you increase the chance of something coming back significant by chance.

Extensions:

This model of criminal behavior has some distinct implications. Before getting into them, let us discuss why prisons exist. There are three purposes for incarceration: incapacitation, deterrence, and rehabilitation. They are, respectively, that it is difficult to commit crimes while locked up; that the fear of punishment deters you from committing crimes; and that prison rehabilitates you, making you a new and better person. Researchers have found very limited evidence that post-conviction imprisonment has any effect, positive or negative, on later recidivism. (See here). Judge IV studies are more likely to find criminogenic results, while studies based on a discontinuity in sentencing laws tend to prevent it. Programs focused on rehabilitation seem to help (though again, we only know on the margin). The consistent criminogenic results for pre-trial detention indicate that most of the damage is in being incarcerated at all. Given this, we can believe that most of what prison does is incapacitate dangerous people. It’s pretty close to freezing someone for a period, and then letting them go.

We should expect groups with higher crime rates to have higher recidivism rates — as indeed, men do have a higher recidivism rate than females. This would suggest that the length of sentence should be shorter for women than for men. Or consider what it means when someone is arrested for their first offense at a young age, compared to an older age. The modern paradigm in the justice system is that minors are not fully culpable for their decisions, and so sentences should be shorter and focus more on rehabilitation.1 However, being arrested at a younger age indicates that your individual probability of committing crime is higher! We would expect age at first arrest to predict recidivism, and indeed it does. With this in mind, our sentencing is backwards — the younger you are at first offense, the longer your sentence should be, and the older you are, the shorter. The 15 year old arrested for assault with a deadly weapon is probably more dangerous than a 50 year old arrested for the same crime, if neither has committed a crime before.

Prisons in the US should attempt to rehabilitate. They should focus on getting a parolee a job, and on having them complete high school. These are relatively low cost interventions, which may not scale up but do not seem to backfire. We should sentence more people to house arrest with electronic monitoring, especially in pre-trial detention. At the same time, we should be much more willing to throw away the key for juvenile defendants, and more lenient on adult offenders. People show who they are — we have but a limited ability to change them. Some people ought not be allowed to live among us.

This presumes that the youth are more amenable to rehabilitation. We cannot assume this is so. The “Heckman Curve”, which argues that interventions earlier in life are more effective than those later in life, is dead — its whole existence a confusion between whether length of treatment or age at initial treatment is more important (a program started earlier in life can have a longer exposure). The best evidence we have on the impact of juvenile detention is this study, which does find negative impacts for teenagers, primarily through the channel of not completing high school. This indicates we should commit fewer teenagers to juvenile detention, although it does not tell us how long the sentences should be.