Why Tariffs are Never the Optimal Industrial Policy

A journey through the developing world, modern trade theory, and the historical experience of developed countries

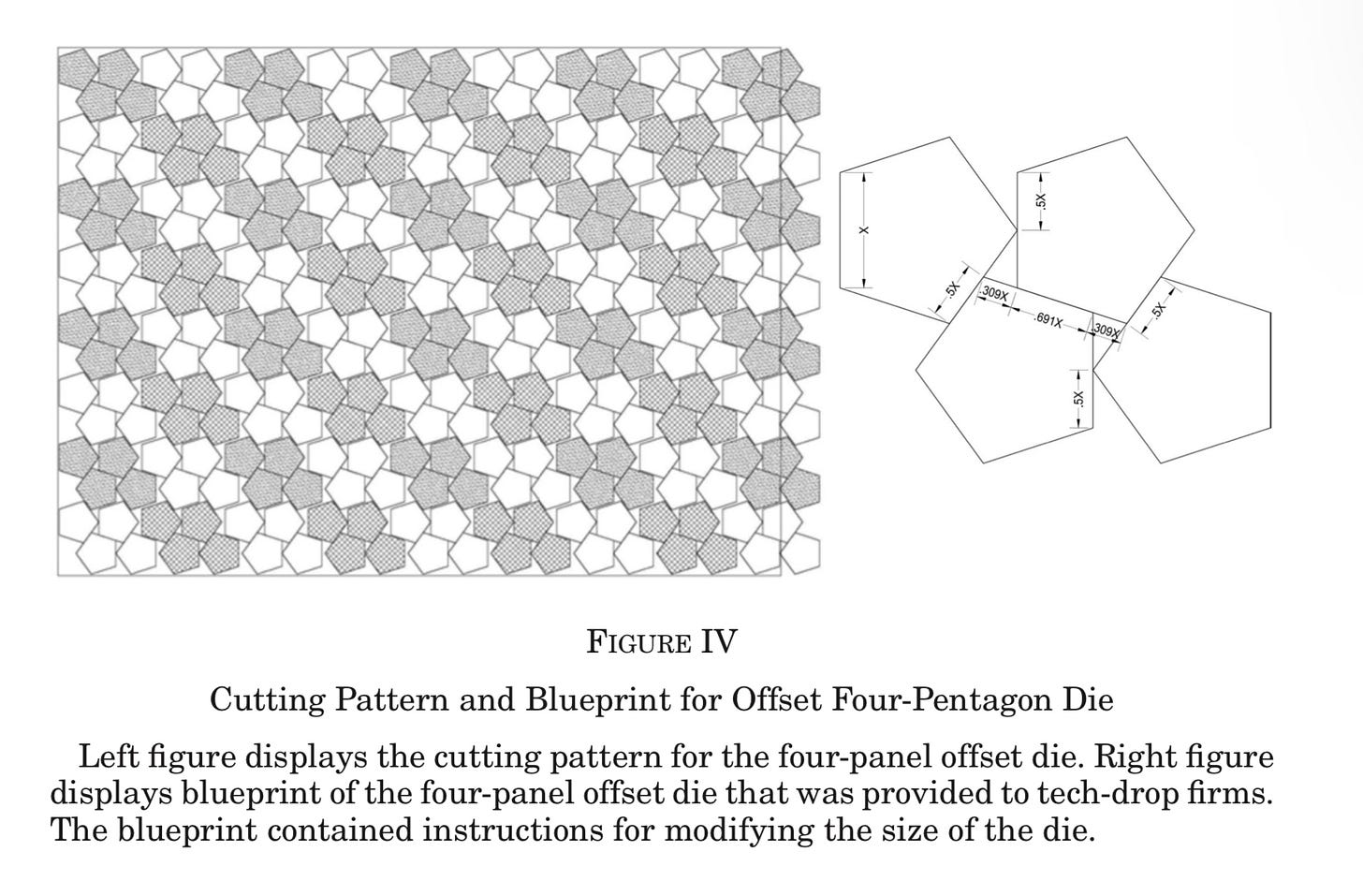

i. Firm Efficiency

Firms in the developing world are inefficient. So inefficient, in fact, that a bunch of schmucks can waltz in and improve things. The year is 2012, most soccer balls in the world are produced in the city of Sialkot, Pakistan, and a group of Ivy League economists notice that they’re doing it all wrong. To make a soccer ball, panels cut from an artificial leather called rexine are either stitched together or glued. The cutting dies which were universally used, though, were not the most efficient possible. They simply put two pentagons or two hexagons next to each other. This is an intuitive arrangement, but not the most efficient possible. By slightly offsetting the die, it is possible to pack more pentagons into the same area of rexine.

The gains are significant – it cut down on wastage by 6%, and increased total profitability by 1%. The average firm could make back its costs after 43 days, and earn pure profit after that for years.

The researchers set up an experiment. To 35 firms, they would give the dies; to 18, a cash equivalent to the die; and to the remaining 79 in their sample, nothing. The whole project cost about $20,000, and so – cackling with glee, I imagine – the researchers waited for the effects to show. Yet, it wasn’t adopted. The very few firms which did adopt it showed marked gains in productivity, but only five of the 35 firms which got the dies for free adopted them consistently.

So what happened? In the case of the dies, the process took slightly longer for workers to do. Fearing that the rates per sheet cut would never be adjusted, workers misreported the effectiveness of the dies, and management believed them. Management didn’t have the slightest clue what was going on.

In this essay, I will argue that differences in management quality explain much of the difference in productivity between countries. These differences are only able to exist because of uncompetitive markets and barriers to foreign trade, and I will show theoretically how trade affects both what is made, and how it is made. I will then show, with evidence from the United States and Latin America, how trade restrictions have led to poor productivity in the past, and what that implies for industrial policy in the present day.

Unproductive management seems strange on the face of it – after all, isn’t management something you can change? This isn’t like importing machinery. The information is cheaply available. If there are large differences in productivity, why aren’t the new ways adopted?

Yet, differences in management are profound, persistent, and well-documented. Bloom and van Reenen (2007) are the first to systematically measure management practices. They find, in their sample of 732 medium-sized manufacturing firms across France, Germany, the UK, and the US, that management practices graded without knowledge of the revenue strongly predicted profitability. They graded firms out of five, with a one standard deviation increase in the management score correlated with a 38% increase in labor productivity. In a later paper (Bloom and van Reenen (2010)), they identify ten big conclusions, which are worth listing in full.

Better management scores predict better everything. There are no tradeoffs.

Management practices vary widely, and so productivity between firms varies widely. In particular, in developing countries like Brazil or India, there is a long tail of extremely poorly managed and highly unproductive firms, which account for a considerable portion of the difference in productivity between countries.1

Different countries and firms have different management styles, and when these firms become multinational, they take their styles with them.

Competition improves productivity, both by getting rid of the crummy firms, and improving everyone.

Multinationals are good at business everywhere.

Exporting firms have higher productivity than firms which sell only on the domestic market.

Firms which are run by the eldest son of the founder are very badly run, and differences in primogeniture customs explain a substantial fraction of cross-country productivity differences.

Government run firms are terribly run firms. Private equity and publicly traded firms are much better.

Companies which have more educated workers have better management scores.

Lower labor market regulations are associated with better management practices.

These cross-sectional data sets could be plagued by omitted variable bias and reverse causality. Perhaps our definition of good management becomes “whatever the profitable firms do”, and it is not in itself causing productivity. We can test this experimentally. In 2013, Bloom, Eifert, Mahajan, McKenzie, and Roberts did a randomized controlled trial on firm management, on some of the hundreds of textile firms in and around Mumbai, India. They got a random sample of firms between 100 and 1,000 employees with 66 potential firms. 34 accepted the offer of participating in the study, of which half would receive intensive management training, and the other half more cursory management training. These firms were not well managed, but typical of Indian manufacturing – compared to a US mean of 3.33 out of 5 on the Bloom/van Reenen management scores, and a mean of 2.69 for Indian firms, these had an average score of 2.60.

You might wonder, what could a few consultants possibly implement? This is not fully grasping how poorly run these firm are run. There were no records. There were no inventories. There were no plans or targets, or any attempt to sell what they had an excess of. Preventative maintenance on machines was not done, and there was no schedule for doing so. The work space was cluttered, disorganized, and filthy. Garbage was dumped in and out of the factory. The excess yarn was not stored in an organized manner, and was frequently destroyed while in storage. These plants were, on average, carrying four months worth of raw materials inventory with them (all of it unlabeled and piled haphazardly in the back). There was no process for recording when, where, and why defects happened, leading to much of their product having to be thrown out. The photos they include in the paper are shocking – it is difficult to believe that people would work in such conditions. (No, you may not look at my room!).

When the firms implemented the management advice, everything improved. Output rose 9.4%. The number of quality defects fell in half. Yarn inventory fell by 20 percentage points (30 percentage points compared to the control plants). None of this was due to outliers. Most importantly, profits per plant rose by $325,000 per year, and total factor productivity increased by 17%. The total cost of implementing the better management was only $4,000. Even including the cost of hiring consultants to do the training ($250,000, once), the program was wildly profitable.

These are astonishing productivity gains for anything, much less a training program (and here in America we think of meetings and training as useless time-sucks!). While it contrasts with some other results of small business training, the textile firms were far more serious establishments than what other work has studied.2 These benefits did not last only as long as the study was conducted, and then no further – when they checked back years later in 2017, the firms still differed in management practices and in productivity. In an encouraging sign, the better practices had spread to other plants owned by the same companies; although not, alas, to other firms.

What’s perhaps more astonishing is why firms did not adopt the practices. They thought they didn’t need them. Most of the 32 firms which refused the offer to participate in the study did so because they did not believe they needed the assistance, (although they may have been committing tax fraud, and were naturally suspicious of anything official). When pressed, they would say that they are doing well enough already, and are doing the same as everyone else is anyway. If the firm is profitable already, why change anything? For some of the more uncommon practices, like “daily factory meetings, standardized operating procedures, or inventory control norms”, firms had simply never heard of them.

This complacency has to be enabled by a lack of meaningful competition. Indian laws make it difficult for multinationals to compete, and there are substantial import restrictions on textiles too. The court system in India is notoriously slow and ineffective (with cases taking decades to wend their way through in the worst cases), forcing firms to rely upon their family members. (Every single one of the 139 textile firms that they surveyed were family owned. And some were even publicly traded!). The size of the firm was three times more correlated with the number of male family members than with their management practices. There is a lack of access to external credit too, largely as a symptom of the poor court system.3

The negative correlation of family ownership with productivity is to some degree the symptom of a trustless, lawbreaking society. Papers on Italy and Mexico allege that the principal reason for firms to stay small and family owned is to evade taxes, leaving them unable to grow and adopt modern information technology. Information is also a non-rivalrous good – if someone goes to the trouble of figuring out new and better practices, the information will doubtless leak to other people. If there is some fixed cost to finding new ideas, then firms will not find the optimal number of new ideas. Bloom et al giving them new ideas, like it or not, is overcoming this public good problem.4

In short, if some firms were to have better ideas, they would not be able to act upon them. Firms are not able to increase to their proper size, and instead they are slack, wasteful, and unproductive. And firms really are able to change course – and change course fast – in the face of competition shocks. Schmitz (2005) looks at iron ore producers in the Great Lakes during the 80s and 90s. Before the construction of the St. Lawrence Riverway, there was no cost effective way to get iron to anywhere in the Great Lakes from outside the region. The iron ore producers of Minnesota held an unchecked natural monopoly since the 1880s. With the lack of pressure came rigid work rules. In order to extract as much surplus as they could, unions insisted on hiring workers to do nothing. Bridgeman (2011) offers a formal model for why unions might insist on work rules, in the context of the automotive industry. If they cannot control the amount that the monopoly produces, then increasing wages is increasing the marginal cost of production, which contracts the amount produced. The price moves further up the demand curve, and there is a part of the rents which the union cannot extract. If they require that a given number of workers need to be hired before any work at all can be done, though, it is equivalent to levying a lump sum tax. The optimal level of production is left undisturbed, and the union can, in theory, extract the entire surplus and give it to their family members.

When Brazilian competition came in the early 1980s, it was as if a switch flipped. At first the mines were devastated, with 25% of mines being mothballed, but within the decade they had almost doubled their productivity per worker and entirely bested the Brazilians. Away went the work rules. Away went inefficient practices. Labor productivity increased by 68%, and total factor productivity increased by 42%. The mines always had it in them, but without competition, inefficiency prevailed. Dunne, Klimek, and Schmitz (2010) documents the same story in the cement industry during the mid 1980s. After World War II, total factor productivity had stagnated, declining by 10% between the ‘50s and ‘80s. When foreign competition came, management could shed the restrictive work rules imposed by unions.

With sufficient creativity, we don’t even need to use changes in tariffs or in foreign competition to measure the effects of trade. A tariff is just one of many reasons why trade is costly; within the same country, we can use a sudden reduction in travel costs to estimate the benefits from trade. Hornbeck and Rotemberg (2024) have a new paper on the effect of railroads on American economic growth, and unlike prior endeavours, (Fogel (1962), Donaldson and Hornbeck (2016), see Decker (2024) for an overview) they have access to firm level data and do not have to rely upon aggregates. They do not need to assume perfect competition. Allowing for misallocation of inputs allows the railroad to lead to enormous gains in productivity, with a one standard deviation increase in the “market access” (a measure of trade costs) leading to a 20% increase in productivity. Firms were limited by the size of their local market, and afterward could produce more of the things they were best at.

Alternatively, you can consider cases of an industry which produces a homogenous good with prohibitive transportation costs. Ready-mix concrete is the clearest example of this; concrete, believe it or not, is really heavy. Once the concrete is mixed at the plant and loaded onto the truck, it will begin to set inside the truck, and must be used quickly.5 Because concrete cannot be cost-effectively transported far, competition can vary widely in different geographic areas. Backus (2020) is able to quite decisively show that not only does productivity increase in areas with more competition, but that it is directly attributable to firms choosing more productive techniques, and not due simply to attrition of less productive firms. Management matters, and we get better management from competition. Backus is following in the footsteps of Syverson (2004), whose results mostly agree with Backus, although the reason why is different. More competitive areas are more productive, but with Syverson, this is because the least productive firms are out of the market entirely.

ii. Trade Theory

We have sound theory that increases in the size of the market should, by themselves, increase the efficiency of firms. Starting with Krugman’s seminal 1979 paper, “Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade”, trade theory has focused on how the size of markets allows for there to be more specific varieties of goods. Assume, as with Dixit-Stiglitz 1977, that each firm produces only one good, and that the production processes for these goods are characterized by increasing returns – for example, there is a fixed cost of entry and constant marginal costs. Consumers have a taste for variety, and benefit from their being more goods. We impose a zero-profit condition, such that firms will enter up until the point that their expected profit is zero. Then as the size of the market increases, the total number of firms which can exist also increases, and consumer welfare increases.

This solved many of the weird inconsistencies of the standard trade models of the time. Prior models like the Heckscher-Ohlin model were based around the factors of production which a country possessed. All goods can be thought of as being the product of land, labor, and capital, and trade will be determined by the relative abundance of them. No longer must we be confused why both Japan and the United States produce automobiles, despite having different factor endowments. Honda specializes in producing Hondas, and Ford specializes in producing Fords. Both of these have declining marginal costs, and we are richer for exchanging the two than if we didn’t.

Conventional tariff analysis takes the set of goods to be produced as given, and then finds the response of quantity supplied to the change in price. (The ratio of the change as a percentage is called the elasticity). The loss to society is the reduction in quantity supplied, and the total loss is area bounded by the triangle between the demand curve, the quantity supplied, and the marginal cost curve. The elasticity of demand for a good is the same as the slope of the demand curve, with a flatter slope being more elastic, and the more elastic the demand for the good, the greater the deadweight loss from the tariff.

This model assumes that there are no fixed costs, and known varieties of goods. A better description of the world is that there are many possible goods yet to be invented, with inventors having to expend a fixed cost to invent it and only receiving part of the gains. Let’s assume that each good is used only by a fixed percentage of the population, and that each firm has a monopoly on its invention. As the size of the market increases, the number of possible users increases, and we get closer and closer to the socially optimal level of invention.6 Because firms have to pay a fixed cost to enter, the long-run costs of increased trade costs are far larger. In the short-run, we can take firm investment as given, and calculate the welfare loss in the conventional manner. In the long run, firms expect the tariff to be levied, and so they avoid ever entering to begin with. Paul Romer gives a simple example in his 1993 paper “New Goods, Old Theory, and the Welfare Costs of Trade Restrictions”, with a simple production function – constant marginal costs and a finite cost of entry which is identical for all goods. Efficiency loss varies with the square of productivity. A 10% tariff rate, if unanticipated, causes national income to decline by 1%. If anticipated, a 10% tariff leads to 19.81% decline in national income. This decline is especially insidious because the counterfactual is difficult to observe. We cannot possibly imagine all the new goods and inventions which could have been made, but weren’t.

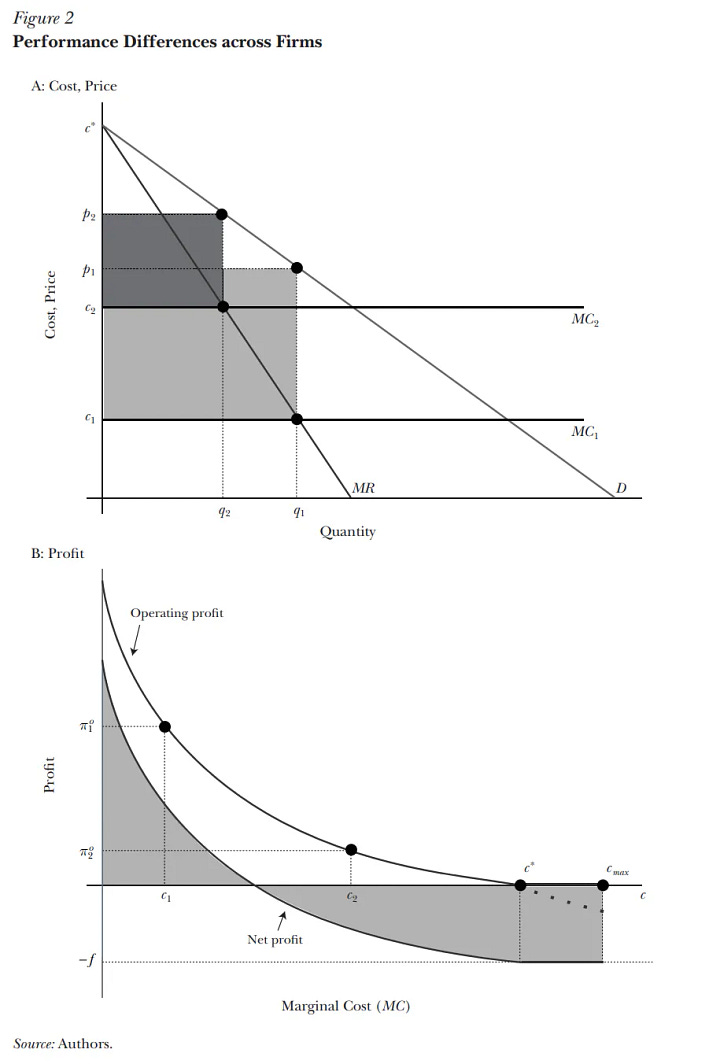

In addition, trade has an effect on competition, and competition affects firms with heterogeneous productivity differently. Imagine, as with Melitz and Ottaviano (2008), that there are two firms in a domestic economy, both of which have different marginal costs of production. Firms price at the point which marginal cost equals marginal revenue, or that is, up until the point that one unit of cost brings in one unit of revenue. Firm 1 faces a lower marginal cost and produces more at a higher markup, as illustrated below. (The figures are taken from Melitz and Trefler, 2012).

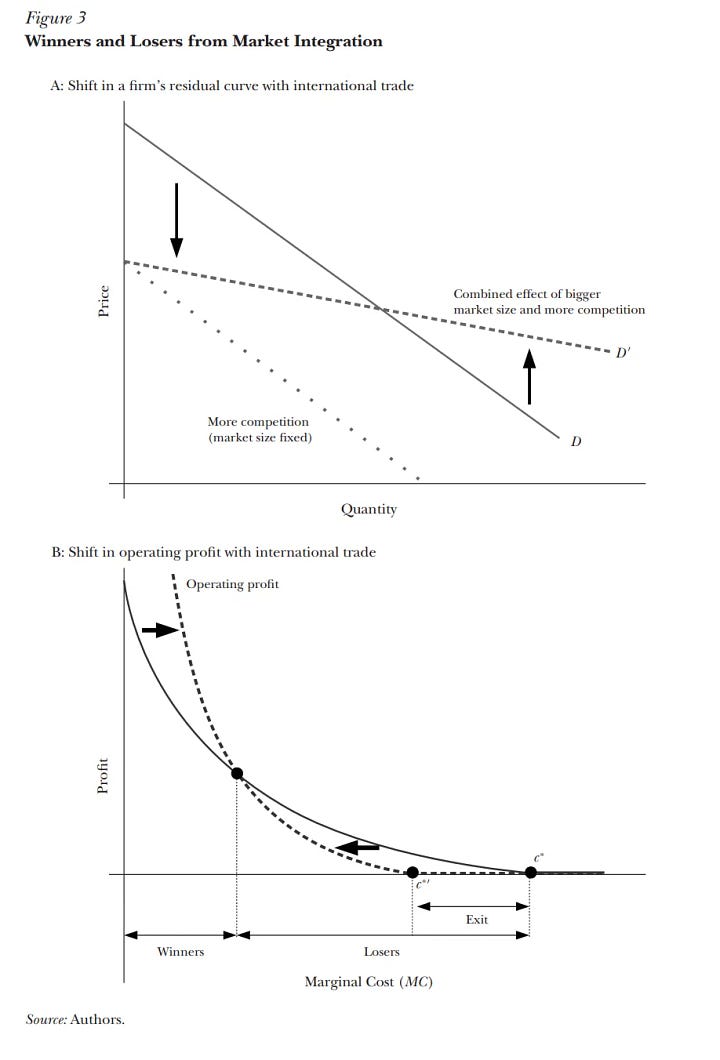

Thus, firm 1 earns a higher profit than firm 2, as shown in panel B of figure 2. (The graphic is assuming that firms pay some fixed cost in order to be in the market at all, equivalent to the line C.) When a country liberalizes its trade policy, as in figure 3, we increase the size of market, thus increasing the potential profits to be made, while also increasing the competitiveness of the market, which flattens the demand curve and reduces the size of markups. It is as if the demand curve is turning. The inefficient, low-markup firms get squeezed out of business, while the efficient, high markup firms benefit more from the market expansion than they are hurt by competition. The inefficient firms must change their technique, or perish.7 The more heterogeneous the firms are, the bigger the possible gains.

Melitz and Trefler illustrate this with the effect of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1989 on Canadian manufacturing firms.8 They cannot, obviously, simply look at the average productivity of plants, which might be trending upwards over time independently, although they do find that it has gone up even after taking into account pre-trends. What is sufficient to estimate gains from trade is the change in the dispersion of productivity by plant, and the correlation of exporting with productivity. They estimate that the trade agreement alone increased total factor productivity by 8 percentage points in seven years through selection alone. The greater market size allowed firms to invest in productivity enhancements with fixed costs too; including this raises overall Canadian manufacturing productivity by 3.5%.

A really cool historical example of why heterogeneity is important was Belgium during the Second Industrial Revolution.9 (I draw from Huberman, Meissner, and Oosterlinck, 2015). Belgium was a substantial exporter, the fifth largest in Europe by 1900. Trade was largely between industries — a textile manufacturer might ship his wares to England and Egypt alike. As trade costs fell, gains from trade occurred primarily in the most heterogenous industries, like tramways and streetcars. The number of goods exported greatly increased. Things like textiles, which used homogenous production techniques, did not see as much of a gain – they were already at the technological maximum for the time. Thus, trade liberalization will have an outsized impact the further from optimal firms are, which means that the developing world especially benefits from free trade.

In summary, there are three non-exclusive channels through which trade promotes productivity. It directly spurs better management, it selects for better firms, and it allows for greater investment into productive technology.

iii. Whither Industrial Policy

We in America are debating industrial policy and tariff protections. In doing so, we must counterbalance the possibilities of increasing efficiency per unit by exploiting learning by doing, against the effects of competition on productivity, from the size of markets on productivity. We cannot speak with certainty for or against it, as there is no way to totally separate out what is due to industrial policy, and what simply correlates with industrial policy. As Scott Sumner puts it, “Some countries are successful. Some countries are unsuccessful. All countries do at least some industrial policy…. From these three facts, we can deduce that:

All successful countries do industrial policy.

All unsuccessful countries do industrial policy.”

We can, nevertheless, speak with some certainty about what sort of policies are likely to achieve our aims. In particular, I wish to highlight the negative impacts of industrial policy which focuses on protecting domestic industries, rather than subsidizing them to compete in the outside world. The reasons for this follow directly from everything which we have seen in the previous section; competition improves the quality of management, which in turn improves the quality of production.

The primary case for industrial policy is learning by doing. If firms' cost per unit falls per unit produced, then the optimal arrangement is to have all units produced by one firm – or if we grant that there are domestic spillovers, by firms within one country. This argument is not necessarily a call for development within the country specifically – Dasgupta and Stiglitz (1988) are extremely explicit that if the learning curves are better in a foreign country than in ours, it is a Pareto improvement to actively subsidize imports. I have no doubts that our present administration is considering this with all due seriousness.

On the face of it, it may seem like there is no difference between import tariffs and subsidizing domestic industry. Both result in the same shift of surplus to industry in the home country. Nevertheless, as per Bloom and van Reenen’s seventh conclusion, exporting firms do considerably better than import substituting firms. Not having to face competition from the outside world encourages complacency and slackness. Interacting with foreign buyers lowers the cost of learning about new products or techniques as well.

The strongest empirical evidence of this in action is a randomized controlled trial (Atkin, Khandelwal, and Osman, 2017) on Egyptian rug manufacturers in 2012. The researchers gave orders for 11 weeks worth of work for foreign buyers, with offers of more if they did the job. They were able to document the profits, quality, and productivity of the exporting firms, and found that all of them rose. When they tested the firms by asking for a standardized order from both treated and controlled firms which would be sold to a domestic buyer, the firms which had access to outside markets produced a better rug than those that did not. The best explanation that the authors have for this is that the intermediaries who placed the order were spreading information about how to make rugs better, and the orders were giving firms an incentive to actually put it in practice.

The historical experience of the United States bears out that tariffs are not responsible for developing sustainable industries, and that any industrial policy will need to focus on encouraging exports. In the United States, the presence of tariffs and economic growth was simply a coincidence. In the first place, the tariffs were largely placed haphazardly, with an eye for revenue, rather than with any coherent attempt being made for industrial policy. During the youth of America, a tariff was simply the only tax it could hope to enforce. The Tariff of Abominations, which sparked the Nullification Crisis of 1832, was essentially an accident – the Southerners attempted to kill the bill by inserting unbearable provisions, in particular a steep tariff on raw wool which Northern industries needed.10

It is therefore little surprise that modern empirical work on the effect of tariffs finds that they were not responsible for America’s growth. Irwin (2000) notes that, if tariffs were to have a positive effect on growth, it would come through increased productivity in the manufacturing sector. Yet, he finds that productivity was actually rather stagnant in the manufacturing sector, and that growth occurred due to an intensification of the usage of capital. Given that tariffs would discourage the importation of capital goods, this suggests that we would have been richer had we had fewer tariffs. Klein and Meissner (2024) are able to use highly dis-aggregated data from the American Gilded Age to show that tariffs reduced labor productivity. Recalling the Melitz-Ottoviano model of trade from earlier, we would expect a contraction of the size of the market to reduce the average size of firms, and reduce average productivity, which is exactly what we find. And, lastly, Yoon (2020) was unable to find evidence for learning by doing – that is, a fall in marginal costs as the number of units produced increases – in the American context.11 Lest you fear that these studies are cherry picked, Shu and Steinwender’s (2019) handbook chapter on the impact of competition on productivity compiles the results of all modern studies. (See tables 2, 3, and 4). They are overwhelmingly positive, with only two or three showing any negative results.

In more modern times, our tariffs have also had bad effects on our own economy. The recent Trump tariffs were passed fully onto consumer prices, and reduced total national income by $1.4 billion per month. (Amiti, Redding, and Weinstein (2019)) The number of varieties available dropped, and since the tariffs were unanticipated, the longer-run effects should be worse. In fact, even the possibility of tariffs being levied depresses industry. Lydia Cox (2023) looks at the downstream effects of tariffs to protect the steel industry during the early George W. Bush administration. Since steel is an intermediate good in the production of other things, the number of jobs in downstream industries vastly outnumber the jobs in steel, by a factor of 80 to 1. The imposition of tariffs led to an immediate decline in the downturn in exports. These losses were persistent. 8 years later, exports were still down 4% – or in other words, between 10 and 50 billion dollars less, with losses concentrated in sectors which heavily use steel. The affected industries have 168,000 fewer jobs than expected. The persistence of the loss can be explained only by a fear that tariffs might be reimposed again in the future. Firms are risk-averse12 and will be hurt more by the loss of their sunk costs than they benefit, magnifying the impacts. Countries would do well to bind their hands, so that they may never be even tempted to impose tariffs, for good or ill.13

Latin America has also suffered for its lack of competition. Clemens and Williamson (2002) show that real tariffs were higher than Europe’s, or anyone else, before World War II. Their total factor productivity is extremely low (Cole, Ohanian, Riascos, and Schmitz (2004)). The authors of that paper argue that differences in human capital are insufficient to explain it. They compare favorably to their peer nations in Europe and the West. In fact, the ratio of human capital to output was 140% of the United States. Moreover, the trends are wrong – human capital was increasing in Latin America, at the same time that productivity fell. Rather, Latin American nations have enormous barriers to competition, including tariffs, quotas, non-market exchange rates, and state owned enterprises far exceeding that of even Western Europe. Everywhere you look, the firms protected from competition grow indolent and inefficient, and countries suffer for it.

Chile is a welcome exception to the trend in Latin America. Cole et al. cite the example of allowing foreign competition in the copper industry after Pinochet, which led to output increasing 175 percent within a decade. Chile also took action against high tariffs. Between 1974 and 1979, Chile reduced its tariffs from around 100% to a flat 10% ad valorem tariff, and with some blips during the early 1980s, has kept its tariffs down till the present day. Nina Pavcnik (2002) measures the effects on Chilean plants. Plants in the sectors which produced goods which sold on the foreign market became 3 to 10% more productive than those which did not. At the same time, selection happened, as the firms which left the market were about 8% less productive than those which stayed. As the Melitz trade model would predict, the big, productive firms took up more market share as trade barriers dropped. Chile remained committed to free trade, and signed the Chile-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in 2003. Lamorgese, Linarello, and Warzynski (2014) find that exports increased, and the productivity of those firms which exported increased as well. Today Chile is one of the richest countries in Latin America. It is striking that one of the few “countries” which rank ahead of it is Puerto Rico, notable for having the fewest trade restrictions of any of the Latin American countries.

A few lessons can be taken from this review.

Much of what makes a firm productive is difficult to describe or transmit. Management is as much a technology as the computer or a pen. Improving the management of firms can greatly increase productivity. Firms with better management will claim greater and greater market share, improving outcomes, unless there is some outside force preventing it.

The losses from being a closed economy are larger than they might naively appear. International trade is able to transmit better ideas and production techniques, in addition to its positive effects on firm mixture. Developing countries are especially affected by trade barriers, because their quality of management is worse, their firms more heterogeneous in productivity, and their market sizes smaller when adjusted for purchasing power. Industrial policy should have firms sell to the largest possible market. Placing tariffs on imports and hoping to replace them with domestic industry does not work.

This has been challenged by Martin Rotemberg and T. Kirk White (publication hell), who start by pointing out that India does not clean its data at all. The findings of papers like Hsieh and Klenow (2009), who find that simply reducing the variance of Indian and Chinese firm productivity to American levels would increase total factor productivity by 40 to 60 percent are not robust to implementing a standardized cleaning procedure – that is, trimming outliers and cutting plain errors. Bils, Klenow and Ruane (2021) acknowledge the criticism as essentially just, but find that it only reduces it by a quarter. In conversation with Klenow, he expressed his belief that most of the misallocation is just measurement error. I am still willing to believe, though, that there is still a substantially long tail of unproductive firms just from the qualitative evidence.

It is perhaps too much to hope that 160 tailors and seamstresses will be profoundly affected by ten hours of management training over a year and a small cash payment, as with Karlan, Knight, and Udry (2012). Given that large, well-funded studies find positive result, and small, poorly-funded studies find null results, I am skeptical of any meta-analyses which find no effect of business training in the developing world. Meta-analyses are for when the treatments are homogenous, and it is improper to consider heterogenous treatments as meaningful. The big constraint is getting firms to actually implement the training. (McKenzie and Woodruff 2014)

Although I am moderately skeptical of how relevant this is. Midrigan and Xu (2010) look at how binding firm financial constraints are in Colombia and South Korea, and find that they aren’t. Yes, they affect many firms, and they aren’t even small. Nevertheless, firms are able to quickly outgrow the constraints, and save up enough to cover themselves.

I would caution against overindexing on this. The later followup study finding that the benefits persisted argues that the main frictions to information transmission are not the cost of learning new and better ways of doing.

This is a cool example of when trade costs are legitimately “iceberg”. Iceberg trade costs are the modeling assumption that the costs of trade are the same as if some part of the product melts, like an iceberg, over time. Not even the ice trade was like this (Bosker and Buringh, 2020), and relating the cost of trade to the value of the good, rather than the quantity, is unlikely to hold, but its convenience and tractability will likely keep it with us forever.

Perfect competition can be thought of as when there are an infinite number of people, as any indivisibilities are sufficient to take us away from the social optimum.

These sorts of productivity gains are actually necessary for the gains from trade to be very large. The gains from international trade from comparative advantage, or even from changes in firm composition, actually aren’t all that large. Arkolakis, Costinot, and Rodriguez-Clare (2012) show that the gains from welfare from trade can be calculated with only two statistics: the domestic trade share, and the elasticity of that trade with respect to transport costs, provided that the trade model has a constant elasticity of substitution. They calculate that the total gains from trade for the United States ranges between 0.7% and 1.4%. Eaton and Kortum (2002) calculate that the cost of moving to total autarky (no international trade) from the level of trade in 1990 would be between 0.2 and 10.3%.

In my view, though, Melitz and Redding (2015) ably defends Melitz’s initial work against the challengers. They show that ACR (2012) is dependent upon their being a smooth and constant Pareto distribution of firms by productivity. If this is truncated – and it seems obvious that it would be – the elasticity of trade is not constant in all contexts. Thus, the welfare effects are not constant either, and can be unboundedly large. And of course, it says nothing about productivity improvements – changes in product, in other words.

They are relying on earlier papers involving Trefler for this; the relevant studies are Lileeva and Trefler (2010), and Trefler (2004).

That is to say, between 1870 and 1914. The second industrial revolution is distinguished from the first by the primacy of science in causing technological change. During the first industrial revolution, technology advanced and science explained, as best it could. (I recall an anecdote of a French scientist hearing reports of a working steam engine, and conclusively proving that such a machine was physically impossible; I make no guarantees for its provenance). Scientific theory guided researchers more in the second, as the products became ever more complex.

I think a detour warranted to explain why a tax on an intermediate good is never optimal. Firms produce goods using a mix of products, and presumably choose the most efficient way of producing a good. A tax on an intermediate good would cause as great or greater a distortion than a tax on the final product. If markets are perfectly competitive and the demand for the intermediate good is perfectly inelastic, then they are equivalent; otherwise, a tax on the finished product would be better. A tax on an intermediate good could be justified if there is no other way to tax the final product, and the revenue improves social welfare, but that seems unlikely to be necessary then or now. The key paper is Diamond and Mirrlees (1971) – refer to section 5 for a discussion of extensions, including intermediate good taxation. Aggregate production efficiency is best, even when perfect redistribution is not possible.

There exists a literature on whether trade increases productivity. I do not believe that those papers, such as Frankel and Romer (1999) and Alcala and Ciccone (2004), are sufficient to make causal claims off of. The cross-country growth regressions of the 1990s were a mistake — it is unclear what we should control for, or if we can ever hope to control enough to make serious estimates. Frankel and Romer’s claim that geography is uncorrelated with present day income except through its effect on bilateral trade is … baffling, and in truth I cannot follow how it was published. The Alcala-Ciccone paper attempts to control for institutions using the Acemoglu-Johnson-Robinson settler mortality data, which is a weak and rightly challenged instrument — I agree with Albouy (2011) regarding its shakiness. I have not reviewed the literature on this exhaustively, but I doubt that there is any possible instrumental variable which would convince me to seriously believe it.

I highly recommend reading Bolotnyy and Vasserman’s 2023 paper, “Scaling Auctions as Insurance”, for this in action.

I simply must smuggle in a reference to Kydland and Prescott’s 1977 paper “Rules Rather than Discretion”. The problem faced by the social planner is the same as faced by the central bank. Even if everyone knows what the optimal social plan is, the planner is not incentivized to stick to it at all times. In order to maximize social welfare, the planner may need to commit to incentive compatible rules which are not optimal. That isn’t to say that trust can’t happen! But given the conduct of our presidents, it is a trust which has long since been squandered.

Really nicely put together article! I appreciated how well reasoned you were. A lot of it is, admittedly, quite beyond my knowledge, so apologies if my questions below don't make sense :)

Regarding South America and Chile - you remark that Chile is "a welcome exception to the trend in Latin America", but I am not following what you mean by trend. From what I can gather, tariffs have been either stable or lowering in general (outside of some specific goods?). Is there another dimension that suggests there is an anti-globalization trend in SA?

I am particularly curious about Peru. It seems like it has even lower tariffs - 2% weighted average in 2022 (https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/PER/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/all/) compared to Chile's 6% (https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/CHL/Year/2022/TradeFlow/Import). While there do seem to be more non-tariff protection measures, they seem to be adopting more open policies - They also opened a new port late last year (https://www.aiddata.org/blog/chancay-port-opens-as-chinas-gateway-to-south-america). At the same time, the average GDP per capita in Peru was less than half that of Chile in 2022 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_South_American_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)_per_capita). Does this suggest that Peru is poised for significant growth in the future? Or, is the gap entirely explained by the remaining factors you mention (quotas, non-market exchange rates, and state owned enterprises)?

Thanks for sharing your writing!

Great article. When you talked about tariffs vs subsidizing domestic production, One thing that I thought should have been elaborated a bit. If a country imposes tariffs, it distorts both the consumption and the production, relatively speaking. Consumption of the tariff imposed goods falls and its production rises--two distortions. But if there is a subsidy on domestic production, it will only distort production not consumption. Ceteris paribus, should the production subsidy be better (less worse) than tariffs?